Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

President Trump’s supporters and detractors alike would agree that the first few weeks of his second term have featured his administration’s aggressive assertion of executive power. The new administration has, without waiting for Congress, dismantled the U.S. Agency for International Development, largely neutered the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, turned immigration enforcement around, sought significant personnel reductions across virtually all federal agencies, and fired or replaced numerous senior officials—such as inspectors general and the head of the Office of Special Counsel—who are at least nominally entitled to some limits on their removal.

For many in the conservative legal movement, the Trump administration moves are significant because they tee up, for judicial resolution, important aspects of “unitary executive” theory. The quick and dirty explanation of the theory is that, constitutionally, all executive powers granted in Article II of the Constitution flow through one person—the president—and, because any authority granted to executive officials other than the president is a delegation of those powers, limits on presidential ability to control any executive branch official, up to and including removal, are unconstitutional.

There are counterarguments to be made, and most likely the Supreme Court will draw some kind of lines. I doubt that all civil service protections for lower-level employees and government employee union contracts will be voided by the court under unitary executive theory, but I wouldn’t be optimistic were I an inspector general or other Senate-confirmed executive branch employee looking to keep my job. But these legal questions (and related executive power questions of impoundment) are already making their way through the federal courts, threatening to slow down or delay, at least temporarily, the Trump train with respect to expanded executive authority. The administration may well prevail in the Supreme Court on many of its “unitary executive”-based arguments, but that will take time.

Enter civil rights enforcement, wherein the scope and breadth of current laws create a much more powerful tool for executive action than many realize, and on topics that go well beyond voting rights or traditional intentional racial discrimination cases.

The reality is that America’s civil rights laws and federal enforcement mechanisms provide an established and well-defined path to quickly implement policy goals without the need for new legislation or any constitutional challenges to existing law. Robust executive action in this realm can drive changes in behavior of major institutions—higher education, corporate America, and state and local government—immediately, even if key questions surrounding the legal theories undergirding the actions are unresolved. Early indications are that the Trump administration is poised to use every ounce of its authority in this regard.

Most Republican administrations have focused on reining in perceived excesses of Democratic predecessors when it comes to civil rights. Republicans have, for example, been skeptical of the overuse of “disparate impact” cases that rely on statistical disparities in outcome rather than evidence of intentional discrimination when it comes to employment law (such as claims of “gender-based discrimination” over physical fitness standards for police and fire departments) . They have also generally been more reluctant than Democrats to intervene on state and local law enforcement in the name of civil rights (in this case usually related to excessive force or other race-neutral constitutional violations), owing both to deference to principles of federalism and substantive “law and order” politics. Thus, typical criticisms of Republican civil rights enforcers are that they are “turning out the lights” or not being as active as they should be.

But look for a Trump civil rights agenda to be more ambitious and, rather than merely limiting the use of tools that have been sharpened by Democratic predecessors, to use the same tools to achieve different ends.

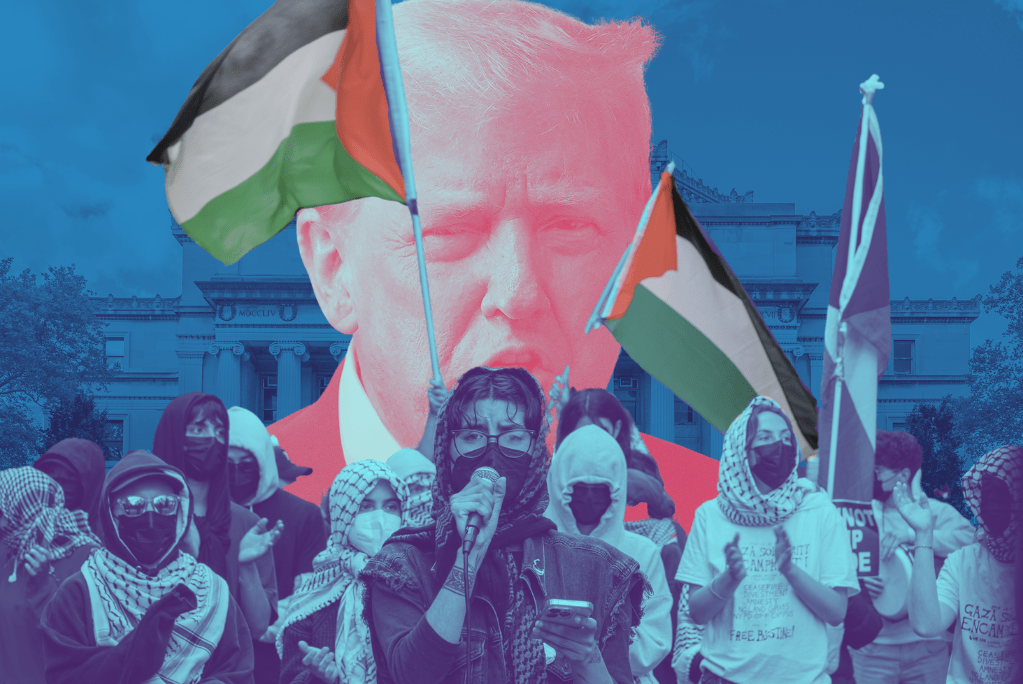

The administration’s termination of $400 million in federal aid to Columbia University over its failure to sufficiently combat antisemitism (and thus in violation of its Title VI obligation not to engage in religious and/or national origin discrimination) provides an example of this approach. Recipients of federal grants are bound by civil rights laws, particularly Title VI of the Civil Rights Act. So-called “spending statutes” (like Title VI and Title IX) are a powerful tool for withholding federal funds in response to discrimination, as the administration defines it. And a Trump administration will define “discrimination” quite differently than Democratic administrations typically do. Do DEI programs (even those unrelated to specific hiring or admissions criteria) “discriminate” against whites and males? There are certainly arguments to be made, depending on the specifics. Do disciplinary proceedings for sexual harassment or assault that don’t allow cross-examination of complainants, don’t adequately define charges, or use a single administrator to both investigate and determine discipline discriminate against males? There are non-frivolous arguments in favor of each of these propositions. Should the Trump administration aggressively threaten to withhold funds based on finding that these practices are discriminatory, its civil rights footprint could be larger, rather than smaller, than its predecessor.

Past experience shows that aggressive enforcement of funding statutes can force change well beyond a targeted institution to truly transform a class of institutions and even society as a whole. Take Title IX of the Civil Rights Act, which requires nondiscrimination between the sexes in higher education. Today, most people assume Title IX requires equal spending on both male and female intercollegiate athletics. It doesn’t (at least explicitly). But for years of Democratic administrations, anything other than rough numerical parity in athletic scholarships resulted in threats to federal funding, Title IX investigations from the Department of Education, legal fees, and public relations headaches. Eventually, colleges got the message and cut many men’s sports (such as wrestling) that impeded the ability to reach numerical parity. What was once a contested interpretation of a generalized nondiscrimination statute became de facto the law, based largely on the aggressive use of a funding statute to drive change.

Similarly, the liability from tolerating a “hostile environment” is a large part of the genesis of the various forms of diversity or sensitivity training that are ubiquitous in all workplaces today. Institutions know that not discriminating is not enough—they must sufficiently educate or police everyone within their institutions to be able to defend against a claim that they tolerate actions that create a hostile environment. There is generally no independent legal requirement to have these mandatory trainings—but institutions, as with colleges and Title IX, learned the lesson.

Unlike private lawsuits alleging discrimination, federal funding threats can change policies even without a court ruling. Yes, there are some administrative and legal hurdles an institution can raise trying to preserve its federal funds (and it is unclear to me that all the appropriate “i’s” were dotted and “t’s crossed” with respect to Title VI in the Columbia case, for example), but no institution that receives large amounts of federal funds wants that funding jeopardized while it litigates the question, further antagonizing the source of the funding. Indeed Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania have already implemented hiring freezes based on the Trump administration’s actions against Columbia, understanding at least some risk of similar actions being taken against them in the future. No doubt they are reviewing their policies to seek to avoid at least direct conflicts with the civil rights interpretations espoused by the Trump administration. And Columbia’s case hasn’t even begun to be litigated.

There are other ways a Trump administration civil rights agenda can push its policy preferences via these powerful funding statutes. In the wake of Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, colleges that persist in resisting the dismantling of now-illegal racial consideration in admissions can have federal funds threatened, Columbia style. It will be interesting to see how schools who argued in SFFA that minority representation would plummet absent legalized discrimination for the sake of diversity explain to a Trump DOJ or Department of Education Office of Civil Rights why their statistical profiles haven’t changed if they are indeed “race neutral” as the Supreme Court now requires. Smart university general counsels are already thinking of how they will defend their admissions processes, and are making changes to policies or practices likely to raise the hackles of a Trump administration investigation.

As has already happened in the Title IX space (where Trump has repealed Biden era guidance on gender identity and the adjudication of sexual assault claims and implemented its own), universities must now calculate that violating the basic due process rights of male students in disciplinary proceedings may threaten their federal funds and balance that obligation against their obligation to protect female students from sexual assault. This risk of losing hundreds of millions of dollars annually in federal funding will induce more change in university policies than the scores of successful lawsuits brought by male students discharged under the Biden era guidance against the universities that discharged them.

One can easily see theTrump administration moving their enforcement beyond universities to corporate federal contractors, who are also bound by nondiscrimination provisions as federal funds recipients. The collective corporate moonwalk on DEI initiatives may be partly the result of “vibe shifts,” but it is also due to fear of a claim—either brought by the federal government or supported by it—that a particular program violates nondiscrimination principles. No one wants to be the subject of federal interest when it comes to civil rights enforcement.

Many conservatives will indulge in a certain amount of schadenfreude as this massive federal civil rights apparatus shifts its focus to nontraditional areas that have arguably been underenforced—religious discrimination, discrimination against whites or Asians, sex-based discrimination against men. And there is a certain symmetry to watching the Trump administration “flip the script” on many of its left-wing opponents.

But for those who were hoping for any limits to be placed on federal civil rights authority or for a return to a more restrained view of the role of federal civil rights enforcement, they will be sorely disappointed.

It is now clear that both parties agree that the federal civil rights laws are legitimate tools to advance all kinds of political and policy goals that go well beyond traditional intentional discrimination—the only disagreement is what those goals are. When it comes to civil rights enforcement in the Trump era, don’t expect a slowdown. Prepare for whiplash.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.