Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

In an objective telling of Triumph of the Heart, the story could be taken for a tragedy. The film is set at Auschwitz in 1941. There are no miraculous interventions, no happily-ever-afters. The 10 men at the center of the narrative die slowly and painfully. But, throughout the film, amid the horrifying dehumanization tactics perpetrated by the Nazi soldiers at the concentration camp, the human will for goodness and hope dares to outlast the spirit of despair.

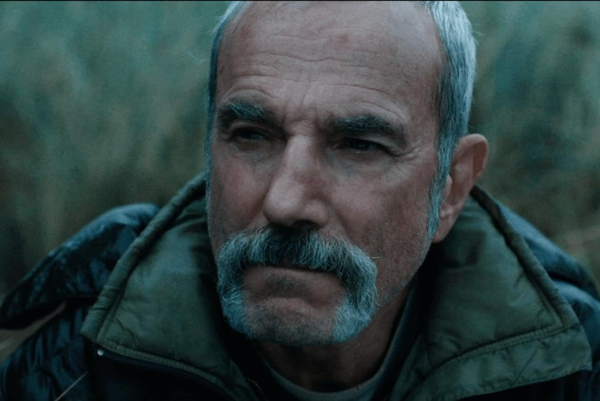

The film portrays the final days of St. Maximilian Kolbe, a Polish Catholic priest, martyr, and, at the end of his life, a concentration camp inmate. When a prisoner escapes, the deputy camp commander condemns 10 men to die by starvation. One of the chosen, Franciszek Gajowniczek, cries out in anguish, saying that he has a wife and children. In the film, Kolbe, played by Polish actor Marcin Kwasny, steps forward after hearing the man’s piercing cries, volunteering to take his place.

The next act takes place in the bunker where the prisoners are to be confined while they starve to death. As they prepare to enter, the guards remove Kolbe’s glasses, a prominent feature of his, perhaps in order to induce demoralization and nihilism: Why do you need to see, if you’re going to die? As the 10 men of various faith and political backgrounds walk into the bunker, a dead man’s bruised and bloodied body is dragged out, a foretelling of what’s to come. Most of the movie takes place in the bunker, interspersed with flashbacks from the characters’ lives and glimpses into the deputy commander's world.

Before detailing the gruesome scenes in the rest of the film, one must grasp the link between Catholicism and Polish identity. The Catholic Church in Poland became a crucial force for political resistance and has helped the country endure persecution for centuries. Alongside the Jewish people, many of Poland’s Catholic clergy were shipped off to concentration camps.

And as the movie shows, they were also dehumanized. In one scene, when a rat scurries across the room and over the men, they fight to grab it. When one of the men’s dead bodies is dragged out, an assistant janitor dumps water to clean the blood from the corpse—and the men immediately rush to lap up the leftover water. One of the men wakes up to find a gun to his back, only to turn around and get savagely beaten by a guard in front of his best friend.

But we also see the men fight back. In one scene, Kolbe motivates the others to sing Polish protest songs until one of the guards comes in and threatens to kill them all. As they lay on the floor from exhaustion, Kolbe exclaims, “We’ve won.”

Kolbe also ministers to the men, but his efforts weren't well-received after a death or brutal beating from the guards. In one scene, as Kolbe encourages the men to say their final confession before they die, one of them cries out in frustration that the whole ordeal is stupid. A few moments later, one of the prisoners confesses that he was the one who gave Kolbe’s name to a German spy, a woman he had fallen in love with. We see the sense of betrayal in Kolbe’s face, but also the realization that he, too, has to forgive in order to be saved.

The film also injects moments of grim humor, a final form of resistance. Kolbe kills the aforementioned rat, and the men stare in shock. “Holy sh-t, Father,” one mutters. But before sharing the raw meat, Kolbe insists they bless the meal. In a grotesque yet deeply human moment, they bow their heads before partaking, reclaiming dignity in the smallest ritual.

In the end, a man in a white coat enters the cell to inject lethal doses of carbolic acid into the remaining prisoners, and Kolbe dies. But the days leading up to his death were filled with incredible acts of faith. You see the madness that descends on humans when a death so unthinkably cruel becomes their fate, you see the human will triumph over succumbing to despair, and you see suffering made beautiful.

I watched Triumph of the Heart on the anniversary of September 11—just one day after the assassination of Charlie Kirk, a few days after the video release which showed the horrific murder of Ukrainian refugee Iryna Zarutska, and two weeks after the mass shooting at the Church of the Annunciation in Minneapolis. Emotionally raw, I hesitated to enter the theater. But after hearing producer Anthony D’Ambrosio explain how he made the film on a $500,000 budget, and encouraged by a friend who had helped crowdfund it, I decided to go.

In the end,Triumph of the Heart is not an easy film to watch—by the time the credits rolled, both I and the man beside me, a burly, Southern type with pickup-truck bravado, were wiping away tears. But it tells a crucial story: a spare, unflinching portrait of sacrifice that insists faith and human dignity still matter when everything else is stripped away.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.