The Supreme Court’s decision in Espinoza vs. Montana Department of Revenue was a significant win for advocates of school choice and, more broadly, for those who believe faith-based institutions should be able to more fully engage in government programs.

The majority was, however, equivocal on a key point—to what extent public dollars can be used for religious purposes. That is the ground on which Espinoza’s supporters and opponents will clash in the years ahead, and there will be clashes. It’s not just about religiously affiliated schools: Nonprofits are engaged in so many education matters—developing curriculum, tutoring, offering online courses, preparing teachers, and more—and many of them are religiously affiliated. In the short-term, Espinoza means more than a dozen states have a freer hand in enacting private-school choice programs. But in the longer term, Espinoza’s ripples could affect state charter-school laws, professional development dollars, state and federal funding formulas, and much more.

Though the seven separate opinions leave a number of questions unanswered, they do forecast where future battles will be fought and suggest, unsurprisingly, that Chief Justice John Roberts will be the key vote.

The court’s Espinoza decision, like the Zelman vs. Simmons-Harris (2002) ruling that school-voucher programs are permissible under the Establishment Clause, is a win for pluralism, educational and otherwise. This particular case is about an education tax-credit program in Montana, namely whether religious schools can participate in a scholarship program funded by private donors who receive a tax benefit for their contributions. But the larger issue is whether public bodies can exclude faith-based organizations from participation in government programs.

At a high level, Espinoza gets at the tension—or what the court has called the “play in the joints”—between the Establishment and Free-Exercise Clauses of the First Amendment. When there is a state program for nongovernmental bodies, is it proper for the state to deny funding to religious organizations as a way to avoid church-state entanglement? Or should the state treat religious organizations the same as secular organizations to avoid discrimination against faith? More specifically, though, the case is about the provisions in numerous states’ constitutions that explicitly prohibit government aid from supporting faith-based institutions (known as Blaine amendments).

The five-justice majority opinion, written by Roberts and joined by the four other Republican appointees, found that a rule created by the Montana state government (based on the state’s Blaine amendment) was inconsistent with the Free-Exercise Clause. Wrote Roberts, “Montana’s no-aid provision bars religious schools from public benefits solely because of the religious character of the schools.” The decision is encapsulated by its crisp couplet: “A State need not subsidize private education. But once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious.”

Roberts’s decision builds explicitly on his decision in Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia Inc. vs. Comer(2017), which overturned a state policy prohibiting a religious organization from participating in a playground-improvement program. The court ruled that an organization cannot be denied access to a state benefit simply because it is faith-based; the Free-Exercise Clause “protects religious observers against unequal treatment.” That decision provided the foundation, framing, and plumbing for Roberts’ Espinoza ruling; “Trinity” shows up 31 times in just 22 pages.

But it is important to remember how narrow Trinity Lutheran was. The decision’s famous “footnote 3” explained that the majority ruled only on “express discrimination based on religious identity with respect to playground resurfacing.” That is, the court was not fully addressing the broader issue of permissible participation in government programs or religious uses of state funds. This modest holding enabled Roberts to get seven votes for his opinion in Trinity Lutheran (including Justices Breyer and Kagan). It is now clear, as many speculated at the time, that Roberts was establishing a precedent, laying the groundwork for an Espinoza-type case. This is particularly important because of a different precedent, Locke vs. Davey(2004), which cuts in a different direction (more on that below).

Despite Roberts’s recent precedent, all four of the court’s Democratic-nominees dissented in Espinoza. But their various paths avoiding Trinity Lutheran show us where the coming battles will take place.

Justice Ginsburg’s dissent (also signed by Justice Kagan) primarily argues that Espinoza didn’t contain a Free Exercise issue to be resolved. Since the Montana Supreme Court invalidated the entire tax-credit program, religious private schools and secular private schools were similarly affected—no private school got a benefit. In other words, there was no actual discrimination against faith-based entities. “There simply are no scholarship funds to be had,” wrote Ginsburg. Interestingly, Ginsburg’s dissent barely touches Trinity Lutheran, raising the question of how Ginsburg would have ruled had the Montana court preserved the program but prohibited private schools’ participation. Kagan, however, signed the first part of Justice Breyer’s dissent, which gets around the Trinity Lutheran precedent in a different and far more pointed way.

Breyer argues a different precedent, Locke vs. Davey, is applicable in Espinoza. In Locke, the court upheld a state scholarship program that prohibited college students from using the aid to study theology. Under that program, scholarships could support a student’s study at a religious school but could not support a student's pursuit of a theology major. The distinction between an institution’s religious “status” and public funding for religious “use” is key, and it foreshadows future litigation.

Breyer’s argument, also found in Justice Sotomayor’s dissent, is that there is a meaningful constitutional difference between banning a group from participating in a public program simply because that group is religious—what occurred in Trinity Lutheran—and banning the use of public resources for religious purposes—what occurred in Locke and here in Espinoza. Breyer argues that excluding K-12 religious schools from a tax-credit scholarship program is closer to prohibiting the use of a state-funded college scholarship for a theology degree (which Locke permits) than prohibiting a religious group from accessing school-playground funds (which Trinity Lutheran forbids). Similarly, Sotomayor cites her dissent in Trinity Lutheran which argues that previous Free Exercise precedents allow “some room” for states to single out religious groups for exclusion. Interestingly, Breyer and Sotomayor marshal a good bit of historical, including founding-era, sources to argue it is legitimate for a state, in respect of the Establishment Clause, to avoid subsidizing faith-based activities.

So, it appears there are at least four votes on the Court—Breyer, Sotomayor, Kagan, and probably Ginsburg—for permitting states some latitude in prohibiting the use of state funds for religious purposes. (For those interested in Free Expression cases, Lemon v. Kurtzman and Employment Division v. Smith are virtually invisible in the various Espinoza opinions.)

However, Justice Gorsuch’s concurrence takes issue with the “status-use” distinction. “The right to be religious without the right to do religious things would hardly amount to a right at all.” This suggests that Gorsuch sees little to no daylight between a law excluding a religious group from accessing public funds and a law prohibiting that religious group from using those public funds to pursue religious activities. If the full court were to embrace that view, the implications would be extensive. But no one else signed Gorsuch’s concurrence. (Justice Thomas did, however, write separately to say the court’s modern interpretation of the Establishment Clause is incorrect and hampers free-exercise rights.)

There are two reasons Espinoza should not, in my view, be seen—at least not yet—as a complete win for free-expression advocates. First, Roberts’s decision does not resolve the status-use question. It recognizes the status-use distinction, acknowledges Montana’s invocation of the distinction, makes clear that the court’s acknowledgement of Montana’s invocation should not be read as the court’s agreement with Montana, and then notes that the distinction need not be examined in this case because Montana discriminated based on status.

So, putting Locke, Trinity Lutheran, and Espinoza together, it appears the court wants a general rule prohibiting states from excluding religious groups from participating in public programs. But there are also some number of votes (perhaps between four and seven) that would tolerate some state limits on the use of government funds for religious purposes.

What the court decides in future cases on the status-use question will determine if Espinoza was a tremor or a Richter-busting earthquake. For instance, if the court were to take the maximalist view of the Free Exercise Clause, it could decide that religious groups can not only run charter schools but also run religious charter schools. It could decide that the federal government must send Title I dollars directly to religious schools educating low-income students instead of requiring that such students get services provided by a secular entity. It could conceivably (though implausibly) decide, as Breyer speculates, that the government is no longer allowed to restrict dollars to the public sector—in whatever domain it is funding, it would need to make funds available to nongovernmental bodies, including faith-based groups. As Breyer writes, “If making scholarships available to only secular nonpublic schools exerts ‘coercive’ pressure on parents whose faith impels them to enroll their children in religious schools, then how is a State’s decision to fund only secular public schools any less coercive?”

Future cases could preserve the status-use distinction by requiring that faith-based groups be able to participate in public programs while permitting specific state limits on their use of government funds. In the next few years, the court will almost certainly face a number of questions along these lines.

For example, what if Montana reinstates the tax-credit program, allows religious schools to participate, but only allows religious schools to use funds from the state-supported scholarships for playground resurfacing (i.e. not for anything related to instruction)? What if a yeshiva seeks to replicate its program as a publicly funded charter school? What if a chapter of the Knights of Columbus wants to use funds from a state grant program to teach students character through a Bible-based curriculum? What if a consortium of Christian, Jewish, and Muslim nonprofits want to start a state-funded teacher-education program that prepares individuals to teach religion courses in faith-based schools?

The other reason Espinoza was more modest than it might have been is that it didn’t directly address the constitutionality of state Blaine amendments. The court’s majority could have ruled that any state provision that explicitly singles out religious organizations for non-inclusion in public programs runs afoul of the First Amendment. Indeed, Justice Alito’s concurrence not only defends states’ rationale for adopting school-choice programs, it also offers a convincing history of the painful anti-Catholic bigotry that undergirds Blaine amendments. He astutely argues that since the court recently considered the racially discriminatory intent behind some laws it should consider the religiously discriminatory intent behind Blaine provisions.

Somesharpobserversbelieve that Espinoza effectively neutered Blaine provisions without overturning them. Indeed, the dissenters suggest that the majority wants to declare such state provisions unconstitutional without coming out and saying so. For instance, Ginsburg writes, “By urging that it is impossible to apply the no-aid provision in harmony with the Free Exercise Clause, the Court seems to treat the no-aid provision itself as unconstitutional.”

I come to a different conclusion at this point. I think Blaine amendment might, unfortunately, have some life left. I think the court can’t render judgment on the constitutionality of Blaine provisions until it has resolved the status-use issue. That is, in future cases, the court will explore when states can and can’t exclude religious organizations and religious activities from public programs. So long as the court agrees with the dissenters that at least some faith-based prohibitions are constitutional, some version of Blaine amendments will survive. I suspect “no aid to religious organizations” will no longer fly; but something like “no aid to religious organizations for the following specific religious activities …” might.

I infer from the Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch opinions that there are three votes to go farther than Espinoza. However, Kavanaugh didn’t write a separate concurrence, and he only signed onto Roberts’s limited majority opinion, not Thomas’s, Alito’s, or Gorsuch’s concurrences. And Roberts’s opinion didn’t declare Blaine provisions unconstitutional, it didn’t resolve the status-use question, and it didn’t overturn Locke. Perhaps there are five votes for those things. But had Roberts and Kavanaugh wanted to do those things, they could’ve. They didn’t. That tells us something.

And, obviously, if one or more members of the court retire in the next few years, as many believe likely, today’s voting blocs on these issues could quickly change.

Though clarification of the Espinoza’s implications will take time, we should not miss the big story right in front of us now: The position of faith-based groups to participate in public programs on the same footing as secular groups is stronger than it was a week ago, and much stronger than it was prior to Trinity Lutheran. The Free Expression Clause has gotten a boost vis-à-vis the Establishment Clause. And public policy must now find ways to more fully integrate faith-based groups in the government’s work.

Andy Smarick is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute.

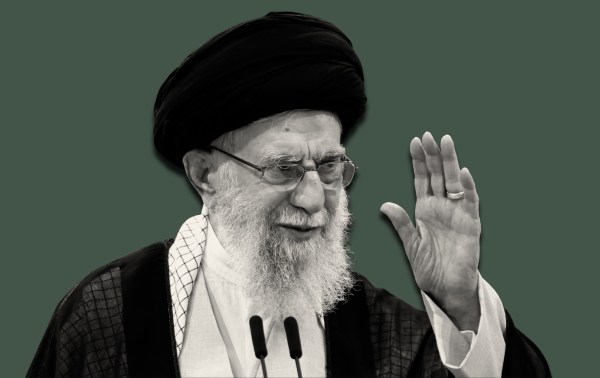

Photograph by Jeff Gritchen/Digital First Media/Orange County Register/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.