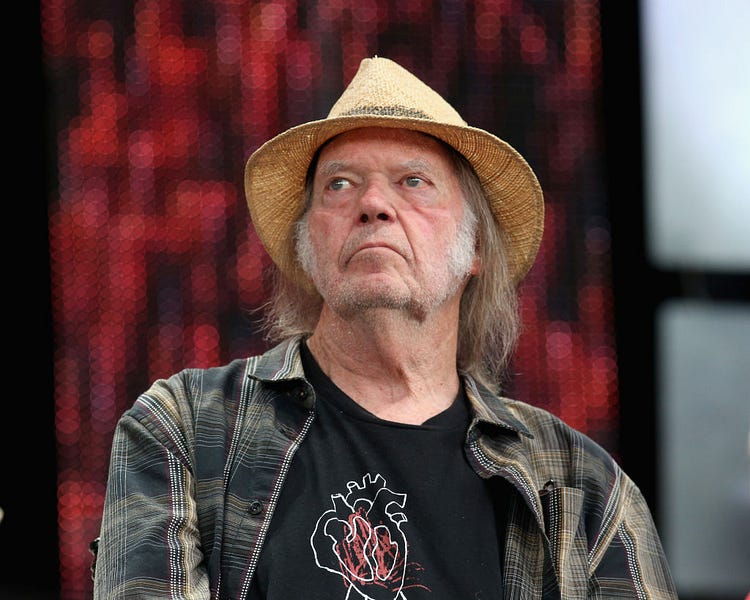

When Neil Young recorded Hey Hey, My My in 1978 with his band Crazy Horse, he was 32.

It is possible that Young knew that one day he would be most famous to a new generation as being the 76-year-old having a very public argument about medical science with a man who had previously paid people to consume horse rectums on television and despaired at the thought of living a long life.

But more likely than him being a seer is that with the lyrics, “It’s better to burn out than to fade away,” Young was talking about mortality and the changing of guard in rock ‘n’ roll. It was around the time of Elvis Presley’s death—“The King is gone, but he’s not forgotten”—and as young punk rockers were leading a frontal assault on the old rock regime, even while falling into the same traps—“This is the story of Johnny Rotten.”

We can’t know what 32-year-old Neil Young would have thought of the 76-year-old version of himself: with a mullet and a fedora that make him look like he works the early shift at a pawn shop and arguing about vaccines with the former host of Fear Factor. Even Young can’t know how the 1978 version of himself would have felt about him now. Our minds do us the favor of sanding down such perceptions over time.

At 32, Young was between the founders of the genre like Presley, who died at 42 as a bloated, cartoon version of himself; and punks like Rotten and his Sex Pistols bandmate, Sid Vicious, who died of an overdose at age 21, even before Young’s song could be released.

“It’s better to burn out than it is to rust,” is a very poignant thought for a rock star looking at middle age and wondering about his legacy and mortality after watching friends die too soon. But for one who is already rusted, it’s nonsense. Young probably enjoys his oxidized condition and feels like he is still doing important, worthwhile work. Burning out and leaving a tragically beautiful corpse would sound stupid to him now, I hope.

It should tell us something about what is wrong with American public life today that the following obviously true statement would be controversial in so many quarters: This is the best era, in the best place in human history to have been born. By the measurements of wealth, health, freedom, equality, justice and opportunity, 21st century America is the bee’s knees.

I can almost hear you out there sputtering! Yes, I know about all of our problems. Yes, I know that things were better for some things or some people at various times, but for the full-spectrum of human experience, we have it amazingly good.

And yet, American politics today is beset with a kind of crazy apocalypticism. I often feel that the various extreme factions all agree that America is doomed, but are fighting over the means of our destruction. They know the end is nigh, but they’re debating what will do us in.

The progressives and the nationalists sometimes even agree on the means, but not the methods. Will racist Big Tech companies turn us all into wage slaves in a dystopia that blends The Matrix with Get Out? Or will woke Big Tech companies turn us all into brainwashed automatons in a dystopia that blends The Matrix with 1984? At least Keanu Reeves will get royalties either way.

Apocalypticism is part of the human condition. We tend to imagine that we are always the obvious end point of human history—what that “long arc” was bending toward all along. And there’s also something satisfying about imagining the end.

The Norsemen told of the impending battle of Ragnarok, when Loki and his son, the wolf Fenrir, would break their chains to descend upon the earth in the The Ship of the Dead and then two other wolves eat the sun and the moon. Not only did that sound totally metal, it also meant that the ones hearing it were one of the final generations before the end. If the Norse soothsayers would have foretold that 1,000 years later, their descendents would be known for their enthusiasm for bicycling and delicious butter cookies, it wouldn’t have sounded as awesome. It certainly wouldn’t have gotten people in the mood for all of the pillaging. “Onward, so that our descendants can enjoy the simple comforts of hygge in the coziest socks possible!”

But this is not Ghostbusters and we do not get to choose the destructor, even if it is a marshmallow man in a sailor suit. Indeed, this fixation on our demise actually keeps us from doing the basics necessary to secure the remarkable good things of the present into the future. Apocalypticism provides us an excuse for not doing the boring, tedious work of governing and finding consensus. That’s even more true when you have identified the very people with whom you are supposed to do this work as the cause of the apocalypse. Nobody had to write an appropriations bill with the wolf who ate the moon.

The soul-sick Americans who attacked the Capitol on January 6, 2021, did not understand that they were living in a place and time where things are good and getting better. It was more appealing and dramatic to think of themselves as combatants in some kind of American Ragnarok. It’s better to burn out than it is to rust, right?

There is another option, and one that requires more courage than the choices Young offered: to build for the future. The correct response to the great blessings we have been given is to invest in institutions and relationships, to love our neighbors, and to plant the seeds for trees, the shade of which we will not live to enjoy.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.