Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

Most everyone is familiar with Thomas Jefferson’s views on cities. “I view great cities as pestilential to the morals, the health and the liberties of man,” he wrote to fellow Founding Father Benjamin Rush in 1800. Years earlier, Jefferson said that the “mobs of great cities add just so much to the support of pure government, as sores do to the strength of the human body.” Instead, Jefferson set out an agrarian vision for the young republic, where republican virtues would be nourished not in overcrowded cities, but among the open lands of a growing nation. Likewise, government should be small and restrained, to allow the protection of individual liberties.

Jefferson’s opposite was Alexander Hamilton, whose vision was decidedly urban and commercial. Their dueling visions fueled the first great factional fight in American history, between Hamilton’s Federalists and Jefferson’s Democratic-Repubican Party. This divide continues to be relevant in our own fractured and fractious age. The red state/blue state divide is the most obvious manifestation of this in 2025—but so is the rural/urban divide, first embodied by Jefferson and Hamilton. American cities—even in many red states—have leaned even more in the direction of the Democratic Party, while the further away from cities one travels, the more Republican the area becomes. Urban and metropolitan areas with higher percentages of college graduates lean Democratic, while exurban and rural areas with smaller numbers of college graduates lean Republican.

This divide is, of course, nothing new. In the late 1800s, the short-lived Populist Party fought for the rights of farmers and other rural Americans. Populists lashed out at the economic powers located in eastern cities, who they believed were throttling the livelihoods of farmers. Their movement was anti-urban and anti-commercial, criticizing bankers and corporations. The fight over Prohibition featured another largely rural-urban breakdown, with cities opposing bans on alcohol while more rural areas tended to be more sympathetic to temperance. The Scopes Trial of the 1920s over the jailing of a Tennessee teacher for teaching evolution likewise saw a division between more rural supporters of teaching creationism in schools, and more urban sophisticates who mocked religious beliefs and attacked opponents of evolution.

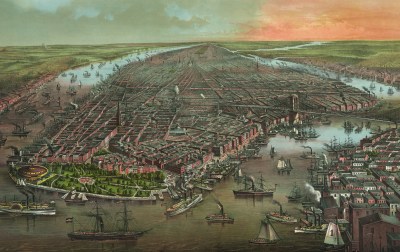

Hamilton’s adopted hometown of New York is usually featured as the central city villain in these divides. Since its founding in 1625 by the Dutch as New Amsterdam, New York has been a polyglot city devoted to commercial and financial endeavors by those, according to the standard narrative, less concerned with religious values and more interested in simply making a buck. It has been an open city where immigrants from other countries, like Hamilton, or those who arrived from small towns across the nation, come to either remake themselves or make a better life for their families.

Ironically, both New Yorkers and those who live far from the city often share a common view of Gotham. They see the city as standing apart from the rest of the country, not really part of America. Many New Yorkers view themselves as cosmopolitans with a jaded view of what they see as the backwardness of the rest of the country. Many living outside of New York see the city as also standing apart from America, representing a set of values foreign to the American republic. Of course, there is also a good deal of exaggeration to this view of New York exceptionalism. Brooklyn was long known as the “City of Churches,” and historian Jon Butler has shown that religiosity and spirituality have a long history even in Manhattan.

Whatever people may think, New York embodies much of what defines American history, from finance capitalism to immigration to arts and music. It would be easy to say that Hamilton has won the argument against Jefferson. In the 21st century, America has very much turned into the kind of nation that Hamilton envisioned: a commercial enterprise that has produced a dynamic economy that has in turn created vast wealth and lifted millions out of poverty. New York, and much of the rest of the country, has welcomed millions of immigrants whose dreams add to that dynamism. Defenders of the Jeffersonian vision in our day, largely those suspicious of both big government and big cities, will not see either of these disappear in our own time. American cities are not going away. They have come to define the modern civilization that began with the Industrial Revolution of the late 1800s and continue to embody what America is today.

Yet cities like New York also continue to struggle with deep-seated problems, some of them Jefferson hinted at: higher crime and disorder, high poverty rates, a greater divide between the rich and the poor. For those who think urban income inequality is a new phenomenon, back in 1885, Protestant minister Josiah Strong wrote a jeremiad against cities. “The rich are richer, and the poor are poorer, in the city than elsewhere,” he noted, “and, as a rule, the greater are the riches of the rich and the poverty of the poor.”

If anything, the rise of mass suburbia in the mid-20th century was a meshing of the Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian visions. Suburbanites could live within close proximity of cities and make use of the economic and cultural advantages that urban living provides, while at the same time exist in a more pastoral environment more conducive to raising families and building communities.

Suburbanization led to the decline of many cities in the post-war era; some, like St. Louis and Detroit, have lost more than 50 percent of their population since 1950. The post-World War II decline of cities and “white flight” led to a sense that traditional big cities were a relic of a dying industrial era. But the 1990s brought a revival of urban living as crime declined and young people discovered the advantages of city life over their suburban upbringings. Journalist Joel Garreau wrote in the early 1990s about the rise of “edge cities” like Tysons Corner in Virginia and the Route 128 Corridor in Massachusetts, which sprouted up outside of traditional cities and provided city-like shopping and entertainment alongside more suburban environments.

Still, in places like New York and Boston, the urban revival has only exacerbated income inequality and led to greater concerns about “affordability” in cities, an idea that Zohran Mamdani has cleverly played to his advantage in his bid to become New York City mayor. And although crime still remains low in most cities when compared to the period before the 1990s, public disorder is on the rise.

While Hamilton’s urban vision praised the kind of economic dynamism found in places like colonial New York, he would be surprised today to see “blue cities” like New York today that are increasingly hostile to capitalism, where high taxes and regulation dampen the economic dynamism that cities are supposed to foster. As urban studies scholar Joel Kotkin has shown, both capital and people are fleeing certain blue cities for places more favorable to business and middle class living—for example, Florida and Texas.

In this environment, Jefferson’s critique of cities persists. And with it, the enduring ideological conflict remains. One group of Americans remains deeply suspicious of blue, progressive, urbanized areas, while another group of Americans sees rural and small-town places as bastions of regressive beliefs. When Hillary Clinton called out the “basket of deplorables” and Barack Obama talked about Americans who “cling to guns or religion,” the not-so-hidden subtext was that they were criticizing less-enlightened, non-urban conservative Americans. It is doubtful that we are heading for any kind of civil war in the near future—despite what some pundits say—yet the cultural and social divide is most certainly real and oftentimes quite bitter.

Historians sometimes have a habit of dismissing contemporary social and political concerns by saying that whatever the concerns are, they are nothing new. As annoying as that habit might be, it is often rooted in truth. Our current polarization owes much to the long-simmering Jefferson-Hamilton divide within America’s cultural DNA, and part of the American genius of these last almost-250 years has been the ability to balance both sides of this ideological divide, to live with the contradiction embedded within a nation that claims both Jefferson and Hamilton as Founding Fathers. How we manage that divide going forward will say much about the health of America as it moves into the next 250 years.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.