Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

Four score and five years after the founding of the American republic, disunion and civil war threatened what President Abraham Lincoln called “the fate of these United States.” Akin to the Revolution of 1776, Lincoln told Congress on July 4, 1861, “This is essentially a people’s contest.”

The struggle tested two things: the very survival of a natural rights republic, and the viability of democratic self-government. On the first, Lincoln pronounced: “On the side of the Union, is a struggle for maintaining in the world that form and substance of government whose leading object is to elevate the condition of men; to lift artificial weights from all shoulders; to clear the paths of laudable pursuit for all; to afford all an unfettered start and a fair chance in the race of life.” And on the second, he declared: “The central idea pervading this struggle is the necessity that is upon us of proving that popular government is not an absurdity. If we fail it will go far to prove the incapability of the people to govern themselves.”

Lincoln was casting the American Civil War, then, as a referendum on the American Revolution. Though the Declaration of Independence gave “liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but hope to the world for all future time,” the rebellion of slaveholding secessionists set loose a national and global trial. Could the Declaration’s universal promise of liberty and equality be preserved for posterity?

As we approach the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, Lincoln’s warnings remind us that the survival of a self-governing republic still depends on our ability to preserve natural rights and equal opportunity for all.

On the same July 4 that Lincoln sent his message to Congress, the newly elected speaker of the House, Galusha Grow of Pennsylvania, delivered his maiden address. He recalled how “Fourscore years ago fifty-six bold merchants, farmers, lawyers, and mechanics, the representatives of a few feeble colonists ... [founded] a new empire, based on the inalienable rights of man.” But on its birthday in 1861, he said, the nation was facing a “rebellion for the overthrow of the best Government ever devised.” Grow even lamented that the now 85-year-old republic had exceeded the Biblical age “of the allotted lifetime of a man.” Perhaps, as in the Psalmist’s words, the United States had surpassed its earthly writ, its life now “labour and sorrow, for it is soon cut off” and destined to “fly away.”

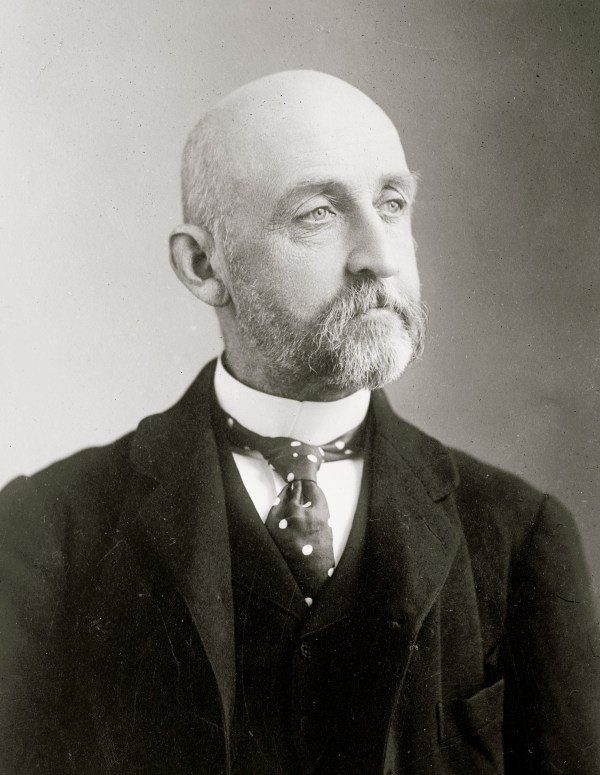

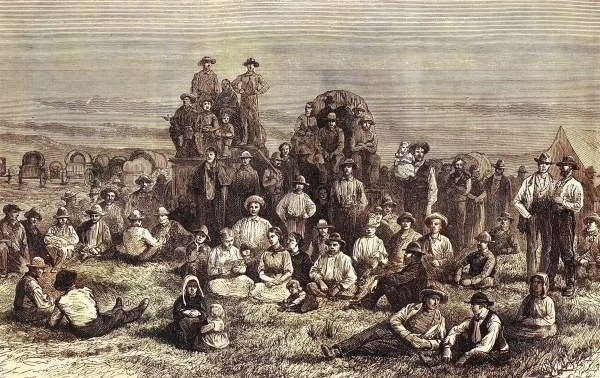

But Grow did not end on a fatalistic note. In recalling the “merchants, farmers, lawyers, and mechanics,” he beckoned a memory of 1776 that appealed to the mass of loyal citizens, themselves descendants of a common American stock. In Grow’s careful words, the fathers who penned the Declaration were neither aloof aristocrats nor populist revolutionaries: The Declaration itself was instead a collective triumph of ordinary Americans. Both the republic’s commonplace forebears and their posterity offered striking contrasts to the noble lords of the slave-driving South. Grow moved the legitimacy of American independence away from the romantic act of rebellion to emphasize the Revolution’s generational legacy: the universal, natural “rights and liberties of the people.” Though largely forgotten today, Galusha Grow’s speech resounded across the Union. Even Lincoln's conspicuous opening lines in the Gettysburg Address echoed the speaker's handiwork.

The national crisis compelled loyal citizens to claim themselves as the just heirs of the Revolutionary generation. And their Confederate adversaries were happy to oblige. Many secessionists appropriated the tradition of Washington and Jefferson in their quest of political self-determination. But the secessionist impulse, at its core, renounced founding ideals. “We do not stand where we stood anciently; we do not stand where our fathers stood upon this slavery question,” boomed the Virginia secessionist Robert M. T. Hunter. Rather than a curse, he said, the institution “is a blessing[,] a benefit to the black man and a benefit to the white.”

At its heart, the secessionists’ revolution was not a political quarrel about tariffs, taxes, or even state sovereignty. It was a repudiation of the Declaration’s pronouncement of innate human equality. So acknowledged the Confederacy’s new vice president, Alexander H. Stephens: “Those ideas … were fundamentally wrong,” Stephens said in a speech in Savannah in 1861. “They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. ... Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.”

Stephens presented the Confederacy as an enterprise in utopian perfection. Proclaiming it “the first [nation] in the history of the world” founded on the idea of racial subordination, he discarded the Enlightenment as a reckless ordeal in intrinsic human dignity, free expression, and individual consent. The prominent slaveholding theorist George Fitzhugh explained further. In “rolling back of the excesses of the Reformation,” the Confederacy was a protest against “the doctrines of natural liberty, human equality, and the social contract as taught by Locke and the American sages of 1776, and an equally solemn protest against the doctrines of Adam Smith, Franklin, Say, Tom Paine, and the rest of the infidel political economists.” In real time, Confederates reimagined history, nature, and religion itself—anticipating a glorious terminus that would end, Stephens assured, in the “disintegration in the old Union” with the Confederacy poised “to become the controlling power on this continent.”

For a Northern reaction to this philosophy, look no further than Lincoln. He denounced the Confederacy as a hubristic parvenu built to “maintain, enlarge, and perpetuate human slavery.” Its bid for continental domination signaled an “approach of returning despotism,” waging “war upon the first principle of popular government—the rights of the people.” For Lincoln, the Civil War tested whether “a government of the people, by the same people” could preserve its integrity. Secessionist triumph would render self-government a folly, transposing constitutionalism with “the essence of anarchy.” A triumphant slaveholding republic would also disclaim the Declaration’s principle of equality. Hence Lincoln warned, “The struggle of today … it is for a vast future also.”

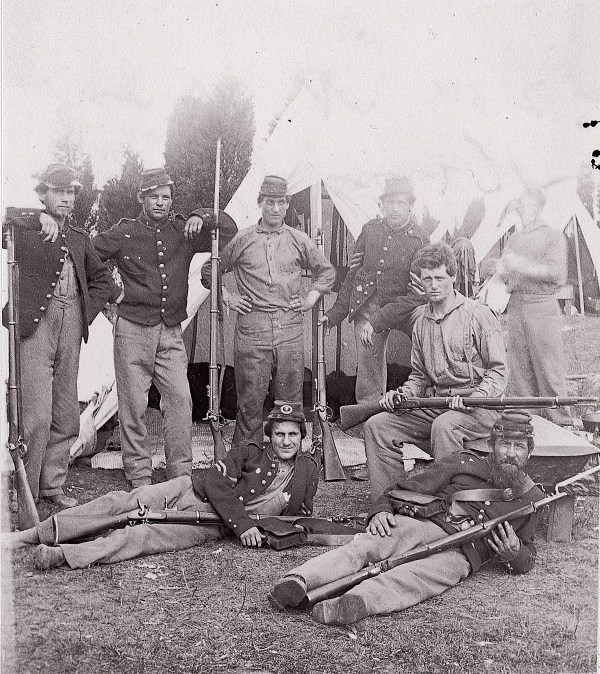

The American citizenry seemed to internalize these stakes. In the dispassionate vein of George Washington, the Union’s citizen-soldiers volunteered to uphold the very government that upheld their individual liberty. Populated by virtuous republicans who had a direct stake in the conflict, so remarked Ulysses S. Grant, “Our armies were composed of men who were able to read, men who knew what they were fighting for, and could not be induced to serve as soldiers, except in an emergency when the safety of the nation was involved.” The sentiments of Sullivan Ballou, a prosperous lawyer and a major in the 2nd Rhode Island Volunteers, echo ubiquitous refrains from countless Union soldiers. “I have no misgivings about, or lack of confidence in, the cause in which I am engaged,” he wrote his wife one week before his battlefield death in 1861. “I know how strongly American civilization now leans upon the triumph of government, and how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and suffering of the Revolution, and I am ... perfectly willing to lay down all my joys in this life to help maintain this government, and to pay that debt.”

The wartime generation of black Americans also claimed the republic, the Declaration, and the Constitution as their own. A sergeant in the 107th U.S. Colored Infantry, Charles W. Singer, called the war “a great battle for the benefit not only of the country but for ourselves and the whole of mankind,” for “While this Government stands, there is hope for the most abject, disabled, and helpless of mankind.” Though long denied political and social equality in a nation that consigned their people to bondage, African Americans also held the founding documents as the means of forming a more perfect Union. Across the nation, black Americans mobilized as free republican citizens. An Iowa delegation counted itself among those “comprehended in the Declaration of Independence,” entitled at once to life and liberty in the equal pursuit of happiness. “Colored citizens of Nashville” credited divine revelation in forming the Union on a natural-rights foundation, “based on the teachings of the Bible, which prescribes the same rules of action for all members of the human family, whether their complexion be white, yellow, red or black.” Abolitionist John Mercer Langston insisted that “the organic law of our nation,” drawn from the Declaration and sanctioned in the Constitution, did not recognize “the color theory” long deployed by slaveholders to corrupt the nation’s founding. And the greatest of his age, Frederick Douglass, saw the Civil War as a fulfillment of the Revolution. It was “a war of ideas, a battle of principles ... between slavery and freedom, barbarism and civilization,” he said after the war, in 1878.

Ballou, Singer, Langston, Douglass, and the black conventions populated the vast “people” about whom Lincoln later spoke at Gettysburg. His famous address, delivered in November 1863, reflected on the nation’s birth in 1776, though the Civil War now tested the founding propositions of natural human equality and constitutional self-government. Unlike the Confederates—and some modern cranks—Lincoln never urged abandoning the allegedly outdated or hypocritical republic of 1776. It was that nation, after all, to which those honored dead at Gettysburg gave their last full measure of devotion to preserving.

Lincoln beckoned “a new birth of freedom” to bring renewed devotion to the oldest of self-evident truths. Thus, when he pledged “that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth,” his arresting use of prepositions reinforced the founding vision of constitutional republicanism. “Of” conveys belonging or origin, the idea that government is not a distant, foreign entity, that it originates from the consent of a sovereign people. “By” bears the rule of law, routine elections, constitutional procedures, and courts of justice. “For” expresses that government exists not to gratify the noble but to protect the people’s natural liberties. Indeed, Lincoln's grammar also suggested that the Confederacy’s own prepositions might have been “over,” “under,” or “to” the people. “Over,” signifying nobility and dictatorship; “under,” denoting secessionist mobs who dissolve legitimate democratic majorities; and “to,” describing a technocratic bureaucracy that deems what will be given or rescinded to a people with little agency or consent. Such were—and are—the world’s oldest forms of tyranny. And they were thankfully superseded by a “new nation” conceived and dedicated now 12 score and nine years ago.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.