Re: the indictment of Donald Trump, a private citizen and resident of Florida—I am perfectly happy to leave the legal questions to the lawyers, and, since The Dispatch has such excellent legal contributors, I will gladly indulge my personal disinclination to wander off into those particular weeds, and I will think of doing so as a passive contribution to journalistic excellence. Though it does not come natural to those of us who write and talk for a living, the old cowboy proverb deserves heeding: “Never miss a good chance to shut up.”

Those caveats issued, a few observations at a comfortable level of generality.

My first instinct is to say, “Let the law be the law—the same for obscure citizens far from the corridors of power as it is for officeholders, former officeholders, and those seeking office.” That is how things should go in a republic, and I do not imagine that very many people of good faith, whatever political allegiances, would disagree with it. If there is to be any variability, it should reflect that those who exercise power or seek it should be held to the highest standards of behavior, both legally and ethically.

There was some video footage making the rounds not long of a DUI stop in which the driver informs the officer who pulled him over that he is a police captain, to which the officer responds: “I have taken an oath to uphold the law. I don’t show favoritism to anyone, regardless. I don’t care if you’re a gangbanger or the president of the United States.” And that is how it should be.

The best case against the case against Trump is that if Trump were some nobody, then the Manhattan district attorney would not be pursuing a case against him. My lawyer friends—including my very anti-Trump lawyer friends—almost to a man believe that this is so, and that is worrying, though there is much about the case we do not know.

There is a legal problem here that isn’t really a legal problem, and not really even a political problem per se, but a civic problem: the problem of discretion.

Police have more work than they can do, and giving them the resources and the mandate to aggressively investigate every possible crime from sea to shining sea would be incompatible with real civic freedom. So, police have discretion about which situations to investigate, which apparent offenders to arrest, etc. And it is good that they have such discretion: We probably don’t want to fine everybody who drives 55.3 mph in a 55-mph zone, we probably don’t want to arrest every teenager arrested with a little baggie of marijuana, etc. While we have in many jurisdictions erred many leagues too far on the side of liberality, we don’t want the maximum possible police response in every shoplifting case, every vagrancy case, or every public intoxication case.

On top of that police discretion is prosecutorial discretion. There is case-by-case discretion and there is policy-level discretion. Both of these can be abused: When a prosecutor decides not to pursue a case against a political ally in the service of his own political interests, that is corruption; when the president of the United States of America decides not to pursue cases against a class of political allies in the service of his own political interests, that’s Barack Obama’s immigration policy—equally corrupt as a moral matter, but not in a way that can be charged as a crime. And, of course, there is a level of discretion on top of that, in effect, at the pre-codification level: Legislators write the laws in such a way that two very, very similar acts may in one case be a crime and in the other case perfectly legal. One result of this is uncertainty—among lawmakers and those expected to obey the law—about what is legal and what is not, as Harvey Silverglate showed in his eye-opening classic Three Felonies a Day. That uncertainty is precisely the opposite of what we are trying to accomplish by writing our statutes down in the first place.

There is a certain kind of mind that is naturally wired to think of the social world as a kind of geometric proof in which we can arrive at irrefutably correct outcomes if we put enough work into refining our principles and then applying them systematically, dispassionately, and consistently. That kind of mind tends to be susceptible to doctrinaire ideology and even fanaticism. (I myself have that kind of mind and have to work against it constantly.) This is the kind of mind that produces the term (and the idea) “social engineering,” which didn’t always express contempt or derision. (We still speak of “political science,” a pregnant phrase that says more than it may mean to say.) Another kind of mind—the kind that exhibits what George Will calls the “conservative sensibility”—understands the world as a series of particulars. That kind of sensibility embraces principles derived from experience and reason but stops short of permitting these to calcify into an inflexible system. That is a more realistic way of looking at the world—taking the world as one finds it rather than trying to hammer all of its organic forms into regular polygons.

In the real world, we need discretion.

The trouble is: Whose discretion?

Conservatives used to talk a great deal about virtue. (Strangely, many of those old virtue entrepreneurs, such as Bill Bennett, very much want you to believe that virtue requires you to bind yourself politically to the habitual liar, serial adulterer, and low-rent scam artist with the business-fraud/porn-star-payoff problem. O, tempora! O, mores!) One of the things I have been trying to communicate for many years is that civic virtue is not some airy-fairy, metaphysical, vague thing that is primarily of concern to us in the hereafter—it is, rather, an eminently practical, here-and-now, workaday consideration. It is impossible to maintain a free society without civic virtue, because a free society requires discretion. Without real civic virtue—putting the good of the republic and the institutions with which we may be entrusted over our own individual interests, at least in any public role we may serve—then discretion simply corrupts everything it touches. And free societies run on trust: If hypocrisy and alcohol are the two great social lubricants, then trust is the great political lubricant of a free society.

To take one example: We have a great deal of trouble with our Internal Revenue Service, which often fails to do the job entrusted to it, in part because people do not trust it, and that mistrust has both a private face (lack of cooperation and active subversion on the part of taxpayers) and a public aspect, in this case the financial and administrative hamstringing of the IRS, mostly by Republican lawmakers. Mistrust of the IRS did not come out of nowhere, and the IRS often has behaved in such a way as to bring discredit on itself and undermine the public trust. The IRS also has some dirt on it simply by being part of a federal government that has done a great deal to earn the distrust and contempt of the people it purports to serve: dirt by association, which isn’t necessarily unreasonable or unfair.

If I thought American prosecutors were reliably trustworthy—that they reliably put the public interest above their own political interests, not in every single case, of course, this being a fallen world, but as a very strong generality—then I would have a very different attitude toward the Manhattan prosecutor’s case against Trump. So would some Trump partisans, I suspect, though by no means most or even many of them. (They exemplify the maxim that a man cannot be reasoned out of a position he was not reasoned into.) If Americans generally trusted the IRS—and if they generally had good reason to trust the IRS—then our tax regime would be a very different one, and could afford to be a more liberal one, because there would be more cooperation and voluntary compliance.

There is a sentiment out there—and I will not pretend that I am above it—that it is somehow unjust that we should be looking to protect norms, standards, and procedures in a way that benefits Donald Trump, who has nothing but contempt for our norms, standards, and procedures, who is as morally and ethically contemptible a specimen as modern American politics has produced, who does not deserve our consideration. It is, no doubt, vexing. But the real question is not what Donald Trump deserves—it is what we deserve, and what kind of government we would have for ourselves. That is the point of all that Thomas More talk you’ve been hearing around here lately.

Maybe the saints and the sages care a great deal about virtue on the eternal timeline. My concerns are more quotidian: Having a government you can trust and institutions you can rely on saves you a hell of a lot of money, time, and trouble. The other kind ruins public life and, soon enough, private life, too. There is no escape from official discretion, and “Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?” is a question that eventually has to be answered with real people in whom we place our trust because we do trust them, because we can trust them.

And Furthermore ...

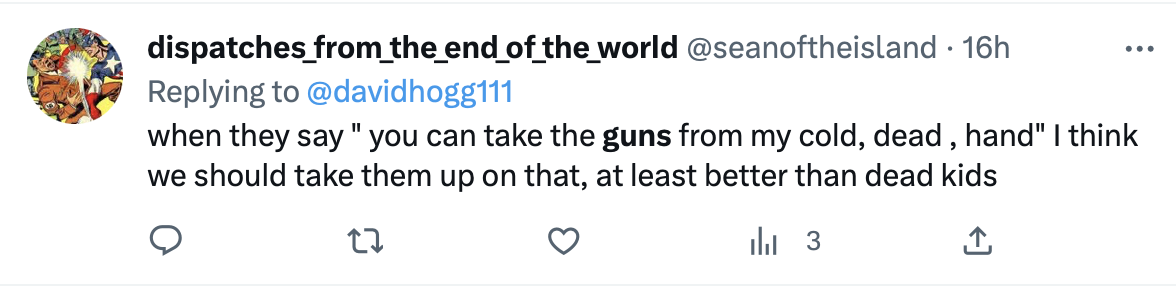

Here’s an interesting point of view: “I’m so committed to a more humane world that I’d be happy to see those who disagree with me murdered.”

Economics for English Majors

Since we are talking about trust: We have talked here in the past about transaction costs, and one group of transaction costs (broadly defined) could be bundled together in what we call compliance costs. For many individuals, families, and businesses, the cost of paying taxes isn’t just the tax bill itself—it is the tax bill plus all of the record-keeping, tax-preparation, and even legal costs involved in figuring out what the tax bill is. Tax law, like every other kind of law, is open to interpretation on certain points, and if you have to spend $500,000 to avoid paying $1 million in unnecessary taxes, then that is $500,000 well spent. But it would be better if you could avoid the unnecessary taxes without spending the $500,000—not only better for you, but better for everybody, since you presumably would either spend that $500,000 on something, in which case the people you spend it with will thank you, or else invest it a way that ultimately helps to finance some productive economic activity, or give it away to charity, etc. Something happens to the money you save, a point that sometimes seems lost on our progressive friends. And if all of the smart and energetic people who do tax-preparation work were liberated to do something more productive with their time, then that would be one more benefit of a more efficient tax system.

There are estimates that U.S.-based businesses spend more on tax compliance than they actually pay in corporate-income tax—meaning that the tax regime produces more income for tax preparers than it does for the Treasury. That is surely the mark of a very poorly designed and poorly administered system.

Every now and then you’ll hear about how the happy people of this or that European country simply get a postcard in the mail tell them what they owe in tax beyond what they already have paid, and that this is paid without any fuss—certainly without all the drama that Americans go through in the run up to Tax Day. I suspect that these stories are exaggerated, like most of the stories we hear about European administrative enlightenment—but not without some basis, either. The way they do health care in Switzerland or immigration in France is not what most Americans would expect it to be, but I suspect that many Americans would prefer more than a few European policies and systems to their U.S. equivalents. (Without going off on a tangent, I will repeat here that I do not think you can have Swiss policies without a country full of Swiss people governed by Swiss culture; likewise, American liberty isn’t necessarily what the Spanish or the Germans need or want or would most benefit from. I am puzzled by those who insist on American exceptionalism and also believe that the rest of the world should do things exactly the way we do, that exceptional America should not be an exception.) That being said, if I ended up saving $3 in compliance costs for every extra $1 paid in tax, then I would count that as a win. (Check my English-major math.) I suspect that many other Americans would feel the same way.

I am skeptical of all political radicalisms and put a little work into being extra skeptical of the libertarian Jacobinism for which I have a natural weakness—the notion that we would be best served by tearing up certain institutions by the roots, starting with the tax code. There are excellent economic and political cases to be made for a tax system that is radically different form the one we have—for taxing consumption rather than income, for example—but those are mostly the stuff of beer-drinking conversations, because we are not on the verge of throwing out the income tax in favor of a VAT, implementing the so-called Fair Tax, going back to funding the federal government with tariffs, or anything like that. There also are unknown costs and unforeseen risks associated with radical changes, and only the worst fools and fanatics imagine that all of these can be foreseen and prepared for.

With all that conceded, it would be better, I think, if we had a tax system that produced more revenue than compliance costs, which ours does not, apparently, at least in the case of corporate income tax. It would be better if compliance costs (both in terms of professionals’ fees and our own unpaid labor) were a great deal lower. And I cannot think of a way to achieve that other than simplification of the tax system: fewer brackets, fewer special cases, fewer calculations to make, etc.

I wonder what Wanderland readers think: Short of some radical program such as abolishing the current tax code and writing a new and better one from scratch, what do you think are the best ways to simplify the tax code? Let me know in the comments and I’ll write them up.

Words About Words

Homer nods: Prisoners are interned in internment camps, while the dead are interred in cemeteries. Many thanks to those who pointed out the error last week. A few readers have suggested that I include the occasional language error to see if anybody is paying attention. I would love to tell you that this is the case, but it isn’t. I make mistakes like anybody else does. If there is a difference, it is that I am interested in mistakes—including my own.

Continuing the wordiness . . .

Thanks to that Wall Street Journal poll, there has been a lot of talk about patriotism this week. David Brooks, writing in the New York Times, has been particularly poetic on the subject: “[P]patriotism gave me a sense of identity and belonging. It ripped me from the prison of the present and placed me in a long procession of Americans—the dead, the living and the unborn.”

I like that.

If you learned Latin with the same once-ubiquitous primer I did, then your first Latin sentence was: “America est patria mea.” Followed by “patria tua” and “patria nostra.” This was often parodied:

America est patria mea.

America est patria tua.

America est patria nostra.

Quicumque, paranoia.

I suppose patriarchy is built into patriotism, patria being the Latin for fatherland, or one’s own country. But as the proverb has it: In the English language, as in life, “man” embraces “woman,” and I suppose there’s a sense of that in Latin, too, not that the Romans were super-sensitive about accusations of sexism. The land of our fathers must, necessarily, be the land of our mothers.

But the sense of nationhood as a kind of corporate fatherhood was very deeply imprinted on Roman culture, as it is on our own. We may have moved past the clan as a unit of social organization (though I am increasingly unsure that we have!) but the history remains in our language.

Cicero was celebrated as pater patriae, “the father of the fatherland,” for his role in putting down the Catiline conspiracy, which you also got a load of if you had the same Latin curriculum I did. (That’s where “O tempora! O mores!” comes from, the speech invariably described as Cicero’s “vitriolic denunciation” of Catiline, a corrupt and bankrupt patrician who convulsed the republic partly out of pique and partly to serve his own financial interests—the OG populist. The Roman class system was more plastic than you might expect: Catiline was from an ancient patrician family, whereas the arch-conservative Cato was, technically, a plebian, while Cicero wasn’t even really a Roman, his people being from a little farther down the peninsula.) Julius Caesar naturally was heralded as pater patriae, as was Augustus, but it wasn’t considered an important title—Tiberius is said to have refused it. It didn’t stop with the Romans: William of Orange styled himself pater patriae, as did King Victor Emmanuel II. There are about 6,000 statues, monuments, plaques, and portraits identifying George Washington as “pater patriae,” because this sometimes purportedly Christian nation never really gave up all that pagan stuff—check out that towering Egyptian obelisk (pater, indeed!) and all those Greco-Roman monstrosities in our hideous capital city.

Pater is related to the English father and the German vater, among many similar father words in many disparate languages. One of those words is the Dutch vader, which should have really telegraphed the big reveal in The Empire Strikes Back. (The second word in Darth Vader is, however, pronounced more like the German vater than the Dutch vader, I am told. Darth doesn’t come from any particular language but instead was chosen because it sounds like dark.) Greek, Hungarian, Hebrew, Swahili—the words for father in many languages exhibit obvious signs of shared paternity. Words for mother are, if anything, even more similar across very different languages: English, Welsh, Vietnamese, Icelandic, Slovak, etc.

One of the lessons we can learn from language is that the fundamental things (including motherhood and fatherhood) really are fundamental.

Elsewhere

The Washington Post has been doing a series on the horrors of AR-style rifles. It is error-ridden propaganda, so they’ll probably win a Pulitzer for it. I have some criticism here and here. For my sins, I expect there will be more.

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

In Closing

This week, Christians around the world will observe Good Friday, the most somber day on the liturgical calendar. The word good in Good Friday expresses an older sense of the adjective: holy, rather than desirable or positive. I always recommend Father Richard John Neuhaus’s Death on a Friday Afternoon—to Catholics, to Protestants, and to non-Christian friends who want to understand more about the religion that provides the basis for the civilization in which they live, in addition to its other, more important purposes. Good Friday is not an observance for the sort of person who insists he has “no regrets.” I don’t know what you do with somebody like that. But for people who understand, even if it is only at some instinctive level, the necessity of penance and reconciliation, Good Friday can be useful and purpose-giving, if not joyous. It isn’t only the joyous things that we need.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.