ASHEVILLE, North Carolina—So, the traffic is definitely a little weird in Asheville right now: a brace of black helicopters overhead, straight out of your favorite conspiracy theory; tight little pelotons of law-enforcement and emergency vehicles rushing down the Billy Graham Freeway with flashing blue lights; a phalanx of black SUVs for the FEMA guys strutting around in their pressed polo shirts; big silver tanker trucks with “POTABLE WATER” emblazoned on them; flatbed trucks packed with diesel generators and ATVs for bringing supplies to hard-to-reach places; trailer loads of bottled drinks and construction supplies, the trucks throwing up dust from highways covered with a thin pink sediment from having recently been underwater.

The sidewalks are pretty crowded, too.

Mindy Belz points out the World Central Kitchen operation, a long line out front feeding Asheville residents who don’t have food to cook or power or water to cook with. She’s seen scenes like this before—in Beirut, in Baghdad, in other unhappy places she worked as a longtime correspondent for World magazine, a widely read Christian periodical based in the North Carolina town. “I never expected to see them in Asheville,” she says. But after the weather reports started using words such as “unprecedented” and “catastrophic,” Belz started storing water and preparing for a rough time. Still, this isn’t what she expected.

This isn’t what anybody expected.

Mindy Belz, Asheville resident“We were completely cut off.”

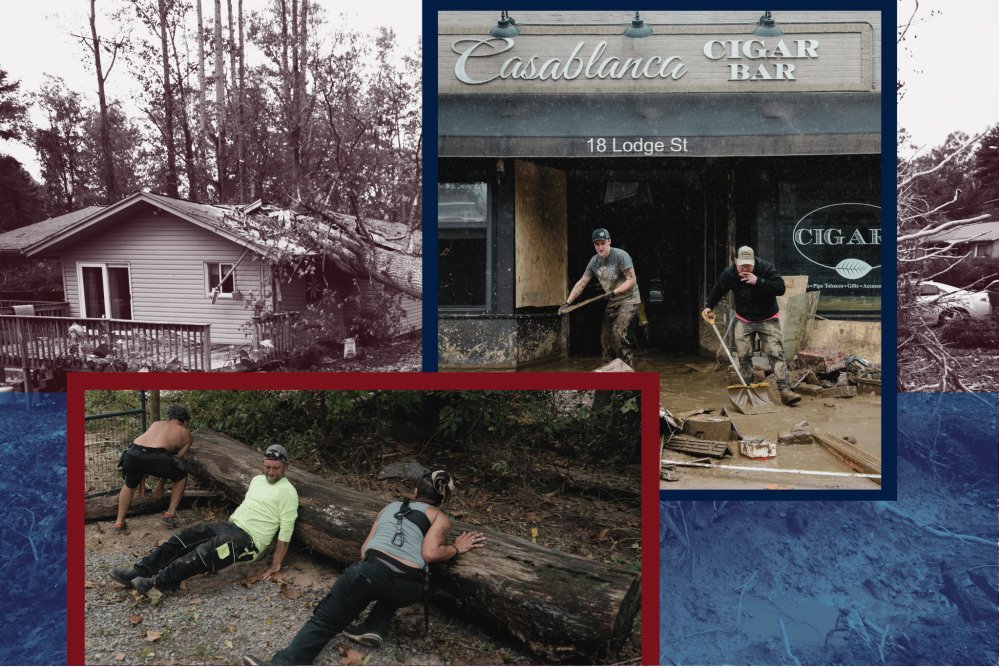

You don’t spend a lot of time planning for hurricanes when you’re up in the mountains at 2,134 feet above sea level and hundreds of miles from the coast. But Asheville was inundated, with two days of heavy rain before the remains of Hurricane Helene came rampaging across the Blue Ridge Mountains and turned the little trickle of the Swannanoa River into a mini-Mississippi, washing out bridges, sweeping away buildings, and submerging houses and other buildings far from the river’s edge.

Except for one section of downtown spared thanks to buried power lines, there’s no electricity—which means no functioning gas and diesel pumps in most of the city. There’s no running water, which means no water for drinking or cooking, for showers or for toilets. Cellular service was out for days, leaving people unable to call for help or to check on family and friends (though connectivity has been intermittently restored). “As technology has become more part of our ordinary lives, the farther you have to fall,” Belz says. “I’ve covered earthquakes. I’ve covered the Beirut port explosion. But to have all of those things at one time …”

She trails off, before adding: “We were completely cut off.”

But Belz came up with a canny workaround. In the past year, she’d spent time at the hospital about a mile away from her house, and she assumed it would have a generator and working Wi-Fi—and that her password would still work, which it did. “That was the only way I got word out to people,” she says, “sitting in the lobby of the hospital.” What the hospital didn’t have was access to usable running water, a problem that it got around with the most old-school solution possible: Workers dug a well, practically overnight.

Wells, printed signs, moving goods on handcarts: There’s a lot of old-fashioned technology that has come back into vogue in Asheville since the storm. Up in the mountains, resourceful volunteers are using pack mules to bring insulin to patients in remote homesteads.

Weird thing is: You can still get a cold beer.

And with sunny skies and temperatures in the upper 80s late last week, a cold beer was a pretty attractive proposition. At the Burial Beer Company, one of those excruciatingly hip little places with which downtown Asheville is positively thick, the owners have been bringing in ice along with the food and other supplies being provided at no charge to anybody who asks. Today, they’re making catfish and BLTs, and by the look of the bacon, they aren’t holding back the good stuff. (Which—why would they? It’s not like the refrigerators are working.) There’s a tip jar out with a fair number of twenties and at least one fifty in it, but no talk of money otherwise. (They are charging for the cold beers.) Down the street at Well Played, a board-game café—like I said: Asheville—they’re open, if not exactly open for business. They don’t have a lot of anything to sell, but they’re keeping the doors open to give people a place to go and something to do while they wait for … not normalcy, because that’s going to be a long wait, but whatever comes next.

People are cheerful and talkative, cooperative, and very scrupulously polite at intersections with dark traffic lights. It isn’t exactly a festival atmosphere, and people are already anxious about the prospects for the city’s tourism-driven economy. Drawn by the famous Biltmore Estate and the city’s proximity to the natural beauty and recreational destinations in the nearby mountains, nearly 14 million people visited Asheville (population: 95,056) in 2023. Nobody knows if they’ll come back.

All that anxiety comes out in other ways, too. Social media and the old-fashioned face-to-face rumor mill have produced thousands of imbecilic tall tales about FEMA refusing supplies or roving gangs pillaging them. There are reports of shooting sprees in the streets and gunfights at the gas stations, none of which are, as far as anybody can document, actually true. State Sen. Kevin Corbin, a Republican whose district includes much of the affected area, wrote on Facebook that elected officials are being swamped by phone calls from constituents terrified about things that are not actually happening:

The state is working non-stop. DOT has deployed workers from all over the state. Duke power has 10,000 workers on this. FEMA is here. The National Guard is here in large numbers. My Senate district is eight counties, and it takes 3 hours to drive across it in good weather. And this disaster is 25 counties in N.C.

The Donald Trump campaign, Fox News, and other opportunistic amoralists are working hard to make Helene the Democrats’ Katrina.

The contrast between the people sweating on the ground in Asheville and comfortable Manhattan media rage-merchants like Jesse Watters could not be more pronounced. In Asheville, which is about 147 percent Democratic, you have bartenders from trendy restaurants and owners of fashionable boutiques—most of them no doubt to the left of Bernie Sanders—all pulling in the same direction with cheerful and capable men whose straw hats and Shenandoah beards announce them as members of some Anabaptist sect or another. Visiting out-of-town police are helping to keep the peace at reopening grocery stores and aid distribution points. It is, by and large, a scene of Americans for once showing their better selves, from urban liberal creative types to evangelicals with one foot still on the farm.

The first person I speak to in Asheville is carrying a big sign reading: “GIVING AWAY FREE WATER + FOOD” with an arrow pointing down the street to the downtown office of City Church of Asheville, an outpost of the Associate Reformed Presbyterian (ARP) Church, a denomination with which I have some personal familiarity.

They’re an interesting bunch. Though their official history in the United States goes back only (“only”) to 1782, they trace their roots back to 17th-century “Covenanters” in Scotland. Theirs is a very, very Scottish church, one whose largest national branch is in … Pakistan. Duff James, the pastor of the City Church of Asheville, embodies something of the contradictions of the contemporary evangelical moment: He is a fit, bearded Gen-Xer with tattooed forearms (a barn swallow and a stylized depiction of the Burning Bush) and an office full of serious books who notes with evident relief that his denomination is one of the few that “went to the edge of theological liberalism but found its way back.” He looks like a man who is at home in a place such as Asheville, but his message—and his presence—haven’t always been welcome. In the early days of planting the church here, he was subjected to a profane and screaming denunciation at a local café where he had been working off and on, hammering away on his laptop among secular-minded Asheville creative types who had wrongly assumed that he was a screenwriter.

“He wanted to know why we would start a church in Asheville. He said, ‘We have a church on every corner, already.’ And I said: ‘Well, which one do you go to?’ He said, ‘None of them,’ and I said that I was here to start one that he might think about going to.”

James describes the church’s mission as the “free offer of the Gospel,” but, at the moment, there’s the free offer of food, water, diapers, and much more to think about. Supplies have been coming in from church members and from others, and there’s a 26-foot-long truck on the way from Columbia, South Carolina, loaded with supplies by a sister ARP congregation there. Potable water remains hard to come by: A woman approaches a church volunteer on the sidewalk and is offered a bottle of water, which she gratefully accepts before asking if she can have some to take with her. They offer her a case and someone to carry it home for her. There’s no sermon except the one St. Francis had in mind when he supposedly (the quotation is apocryphal) advised his friends: “Proclaim the Gospel at all times—when necessary, use words.”

City Church wasn’t ready for this, either, but they figured out a few things pretty quickly. Once it became clear that this was going to be a genuine catastrophe, they started working to account for all of the members of the church: Who was home, and who had left town? Who has a chainsaw? Who has a generator? Who has gasoline or diesel on hand? Who has extra food or water to offer? Who needs something?

Paper charts are taped up on the office walls with the relevant information noted in marker, with a legend explaining the abbreviations. For church services, City Church shares space with a Seventh-Day Adventist congregation who, owing to their doctrine, don’t need it on Sundays. But it also had a downtown office, which put them right in the middle of Asheville’s urban core. The ARP nationally has a heavily rural character—somebody brings in fresh eggs, because of course between the mountain hipsters and the hardcore Presbyterians, somebody has chickens—but in Asheville, it is very much what its name says: a city church.

Duff James, Pastor of the City Church of Asheville“These moments are an unadulterated opportunity to trust God.”

There are public housing projects nearby, whose residents complain the local housing authority has neglected. And maybe hurricane-response isn’t the housing authority’s job—but, then, hurricane-response isn’t really anybody’s job in Asheville, or wasn’t until Helene landed in the city. And so there is one more little chapter added to the great big book of Western Civilization since the fall of Rome, with the City of God picking things up after the City of Man has dropped the ball and the church showing why it remains the one genuinely indispensable institution.

“Our presbytery was mobilized,” James says. “Other churches I had worked with, too, started getting in touch. I’d been at First Pres in Columbia, South Carolina, and they’re coming up with a truck tomorrow. We have others bringing up diapers, wipes, baby products. We’re one of the only places that has diapers and baby stuff.” The nested failures of our material supports—digital communication, electricity, water, diesel and gasoline, transportation—are not lost on a minister who is inclined to see in all things the work of Providence.

“Whether it was the pandemic or Hurricane Helene, it unmoors you from the daily lie that you are self-sufficient,” James says. “These moments are an unadulterated opportunity to trust God, daily, moment by moment. We’re a church that understands that we have been shown grace and mercy by God, and we want to be a conduit of that to the people of Asheville.”

Ross Meyer, an associate pastor at the church, recently returned from mission work in London but originally hails from Tampa—hurricane country. “I’ve seen a lot of hurricanes,” he says, “but I’ve never personally witnessed this level of destruction. We’ve lost power before, but never lost power and water and cell service all at the same time. I’ve been encouraged. Every time we start to run low on supplies and start to wonder about how we’re going to replenish, somebody will pull up in a truck and start unloading pallets of food or more diapers. People are hooking up their own tractor-trailers, driving up here, bringing whatever they can, contributing whatever they have. People want to help. And as people see churches reaching out and helping and loving their neighbors, I hope that people see that as a demonstration of the love of Christ. For people outside of the church, sure, but also for people in our church. It’s been a beautiful thing to see, and we want that to stick around after the power and the water comes back on.”

In 1965, Tom Wolfe and Günter Grass were involved in a discussion at Princeton in which some fashionable radicals insisted that the United States was on the verge of slipping into fascism. Grass, a German social democrat and no fool, was having none of it, and set the students straight. Wolfe tells the story:

“For the past hour, I have my eyes fixed on the doors here,” he said. “You talk about fascism and police repression. In Germany when I was a student, they come through those doors long ago. Here they must be very slow.”

… He sounded like Jean-François Revel, a French socialist writer who talks about one of the great unexplained phenomena of modern astronomy: namely, that the dark night of fascism is always descending in the United States and yet lands only in Europe.

If you want to know why that shadow that sometimes falls across this wobbly republic has not yet deepened into the real darkness that Günter Grass knew too well, go get yourself a cold beer with the hipsters and Presbyterians in Asheville. It’s not pretty, and it’s not perfect, but they’re doing the best they can, and that is really what holds this all together, what makes this country the real and vital power it is rather than a mere parchment republic. Go have a look around and you can see both history and Providence at work, if you have the right kind of eyes. By all means, stay for the sermon.

And bring diapers.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.