Senators have revived an effort to allow more international students who earn advanced science, technology, engineering, and math degrees at American universities to stay in the United States, saying it will boost critical sectors and make America more competitive.

Lawmakers are looking to the Senate’s upcoming debate on the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) as their chance to pass the measure. The amendment, introduced last week by Illinois Democratic Sen. Richard Durbin, would exempt foreign graduates of American institutions with advanced STEM degrees—master’s degrees and higher—from annual green card limits. Admissions would be contingent upon applicants receiving offers to work for a U.S. employer in a field related to their degree.

“America should always be focused on maintaining a strong STEM workforce because it strengthens our economy and enhances our ability to compete on the world stage,” Durbin said in a statement shared with The Dispatch. “By denying international students with STEM degrees from U.S. universities the opportunity to continue their work here, we are losing their talents to countries overseas and won’t see the positive impacts of their American education.”

Sen. Mike Rounds of South Dakota, a Republican, has also signed onto the amendment as a cosponsor. His office did not respond to requests for comment.

Former and current national security officials have been lobbying Congress to pass such a bill, citing a scarcity of workers for important defense industry positions. “The U.S. remains the most desirable destination for the world’s best international scientists and engineers—a feat that China, despite extensive investments, has not come close to replicating,” a coalition of former senior officials, lawmakers, and industry representatives wrote to congressional leaders in May. “Bottlenecks in the U.S. immigration system risk squandering this advantage.”

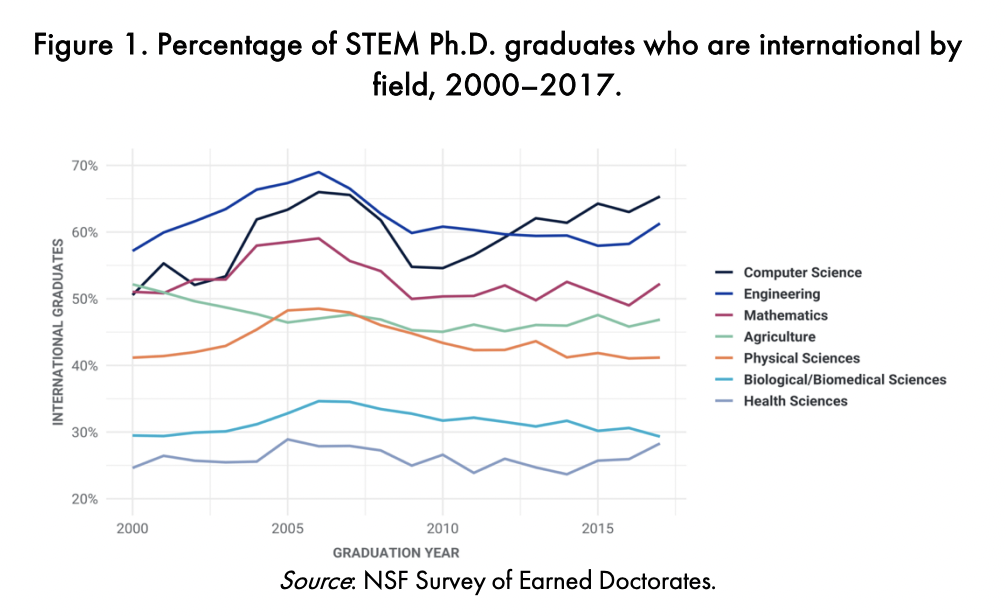

They also noted that nearly two-thirds of U.S. graduate students in artificial intelligence and semiconductor-related programs are born abroad. A 2020 report from Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology underscores the trend and includes data for various degree fields between 2000 and 2017.

Congressional limits for annual employment-based green cards bar applicants from any single country from making up more than 7 percent of recipients each year. In practice, applicants from populous countries like India and China face massive backlogs and decades-long waits.

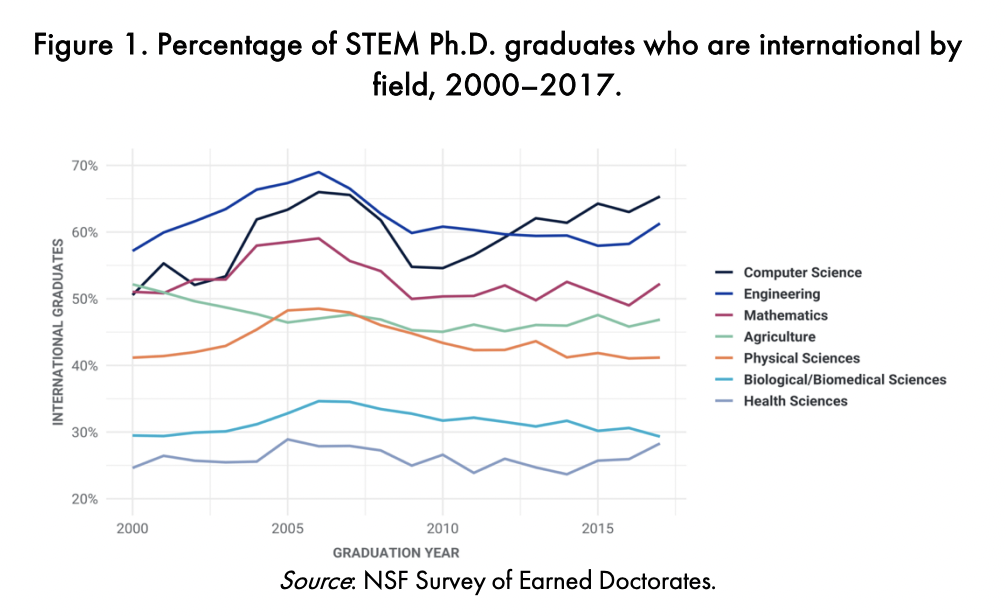

Here’s a different chart from the libertarian CATO Institute visualizing the backlog’s recent growth.

The nonpartisan Congressional Research Service reported in 2020 that nearly 1 million foreign workers and their family members had been approved for and were waiting to receive lawful permanent resident status. That number has only grown since and is projected to double by 2030.

The backlog comes as commercial demand for these workers is high.

“The U.S. immigration system has not kept pace with the changing needs of the economy and national security,” Emerging Technologies Institute Director Mark Lewis and Federation of American Scientists fellow Divyansh Kaushik wrote in an opinion piece last month.

They added that more than 80 percent of defense companies have reported “difficulty in finding qualified science, technology, engineering, and math workers.”

Those shortages, proponents of the bill say, harm America’s “onshoring” efforts to bring advanced manufacturing and key industries to the United States. Lawmakers from both parties have emphasized the need for robust critical supply chains in sectors like medical equipment, technology, and other defense capacities.

The bill has faced Republican opposition and time constraints. Top sponsors and advocates agree its odds of passing are highest with the current Democratic-controlled Congress. And without pre-election politics at play, the lame-duck session after November’s midterms could present the best opportunity to pass it for a while.

Legislation to exempt advanced STEM degree holders from green card limits passed the House earlier this year in a broader China competition package, but negotiators scrapped it from a compromise version with the Senate after Sen. Chuck Grassley, an Iowa Republican, said he would oppose all the House’s immigration provisions because he believed they were “completely unrelated to countering China.”

Grassley’s office did not respond to requests for comment about the new NDAA amendment.

Another attempt to pass the measure failed in July.

The Senate NDAA debate could present new hurdles to passing the bill. Senators would have to find enough buy-in to add it to a revised version leaders will introduce, or they would have to convince leadership to allow a standalone vote on an amendment.

Still, Durbin’s statement sounded optimistic: “This amendment represents a bipartisan, common sense idea that the Senate should take seriously as it considers the NDAA.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.