Welcome once again to The Collision, where we know that, despite events global and domestic, there’s always something unexpected going on in our little corner of the news. This week’s remarkable moment came earlier this morning, when onetime Trump lawyer Sidney Powell took a nice little plea deal just before her trial in Fulton County, Georgia, was set to begin. We’ll get into that, as well as the gag order issued by Judge Tanya Chutkan in the D.C. election-interference trial, a little later.

The Docket

- Donald Trump’s civil trial for fraud in New York continued this week, and the former president made his second courtroom appearance on Wednesday. According to CBS News, Trump appeared “frustrated” and was “shaking his head, throwing his hands in the air, [and] whispering” during the testimony from a real estate executive who said an appraisal of a building the Trump Organization claimed had been provided by him was “inappropriate and inaccurate.” The presiding judge encouraged everyone in the courtroom to be quiet.

- Bizarre drama seems to follow Trump everywhere, including into the courtroom in Manhattan. A spectator at the trial Wednesday stood up in the middle of the proceedings and began to walk toward the former president. She returned to her seat and was later escorted out and charged with contempt of court. One more weird wrinkle—the woman was apparently an employee of the court system.

- What does it mean if a large number of Americans think both parties’ leading presidential candidates might be crooks? The latest Fox News poll, conducted between October 6 and 9, suggests that’s the case, with 52 percent of registered voters saying they believe Trump did “something illegal” regarding either his efforts to overturn the 2020 election or his retention of classified documents. Another 23 percent said Trump did something “wrong but not illegal,” while just 24 percent said he did “nothing wrong.”

- Not quite as many respondents to that same Fox News poll were willing to say President Joe Biden did something illegal related to his son Hunter’s business activities, but 40 percent did—an all-time high since Fox began asking the question in December 2022. Hunter Biden, however, fared just as badly as Trump: 52 percent of registered voters said they thought he had done something illegal.

- A couple more quick looks at the toplines from the Fox News poll, which has a stellar reputation among pollsters that’s independent of the network’s overall credibility: Biden has a 41 percent approval rating, near the lowest mark he’s received in this poll; Trump still holds a strong lead in the GOP primary, boasting 59 percent support nationally to Ron DeSantis’ 13 percent and Nikki Haley’s 10 percent; and Biden and Trump are neck-and-neck in a hypothetical general election matchup, 49 percent to 48 percent, respectively.

The Kraken Pleads Guilty

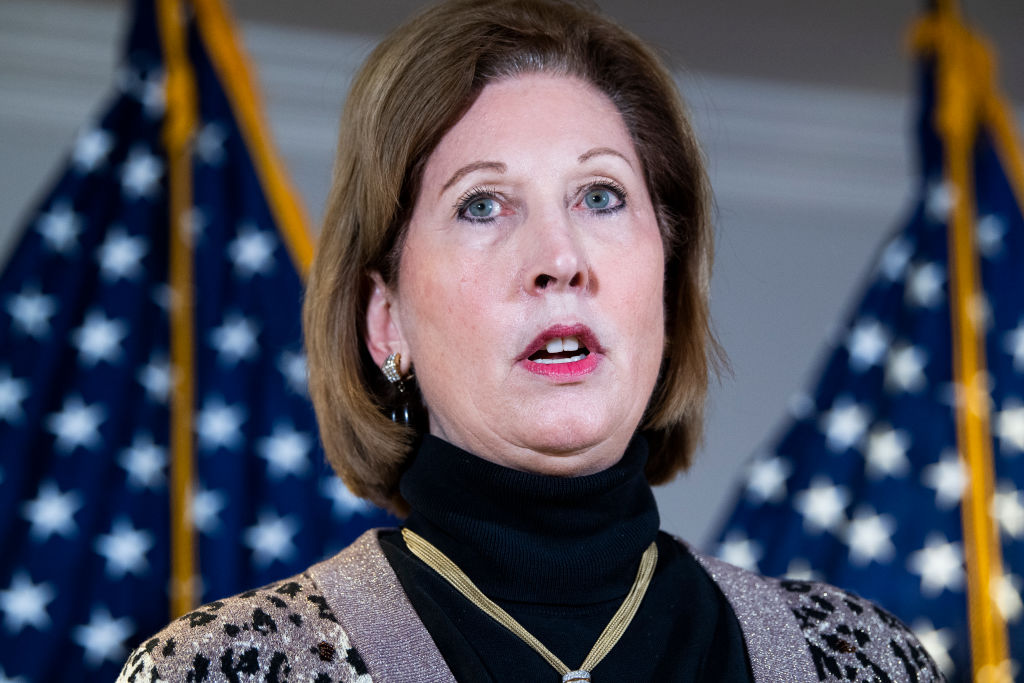

Sidney Powell burst onto the American political scene in late 2020 as perhaps the most bombastic purveyor of Donald Trump’s false claims that the election had been stolen. Her repurposing of the Clash of the Titans battle cry—“Release the Kraken!”—quickly went from a catchphrase for those who believed Trump would be vindicated to a joke after Powell’s claim that there was overwhelming evidence of voter fraud collapsed.

The Kraken is now thoroughly tied up, with Powell pleading guilty in Fulton County, Georgia, to charges she conspired with other Trump supporters—and Trump himself—to disrupt the 2020 election proceedings in the state. Powell received a pretty good deal by agreeing to plead guilty, with the original felony racketeering charges she and her co-conspirators faced being reduced to the aforementioned misdemeanors.

“As part of the deal, she will serve six years of probation, will be fined $6,000, and will have to write an apology letter to Georgia and its residents,” the Associated Press reports. “She also agreed to testify truthfully against her co-defendants at future trials.”

The move wasn’t entirely surprising, since Powell had already gotten her trial severed from Trump’s and sped up. But this is a win for Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis, who has now gotten plea agreements from two people she indicted in August. (The other is Republican poll worker Scott Hall, who pleaded guilty last month as part of a deal with prosecutors.)

The next question is what happens with Kenneth Chesebro, another Trump attorney who was indicted and was going to be tried alongside Powell starting next week. Chesebro may or may not take a similar plea deal, but those conversations were almost certainly happening in parallel to those Willis was having with Powell’s legal team.

“If they offer him straight probation, it might be hard to turn down,” Andrew Fleischman, a Georgia-based defense attorney, told The Dispatch.

All eyes will be on Chesebro, especially after the New York Times reported this week on some correspondence in late 2020 that appears to undercut one of Trump’s own defenses for his actions involving Georgia’s election. While the former president’s lawyers have insisted that he pursued his efforts to overturn Biden’s victory based on legal advice he was receiving from Chesebro, Powell, and others, one email Chesebro reportedly sent during some internal deliberation about whether to file a lawsuit in Wisconsin indicated he viewed his contribution as “political,” as opposed to strictly legal, advice.

Gag Me With a Spoon

Let’s turn to the federal election interference case in Washington, where earlier this week, Judge Tanya Chutkan issued a gag order preventing Trump from disparaging witnesses, prosecutors, and court staff in the run up to his trial, which is currently scheduled to start in March. So what does this actually mean and what does it do? And is this normal?

Let’s start with that second question. Gag orders aren’t that unusual in high-profile trials; there’s a reason you’ve probably heard of the term. In 1997, the judge overseeing the trial of Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh issued a gag order to all lawyers involved in the case, preventing them from publicly discussing evidence or even what was happening during the trial proceedings. That order was extended to all local law enforcement during the trial of McVeigh’s co-conspirator, Terry Nichols, after both legal teams complained that local law enforcement officials had been leaking information about the trial’s security provisions.

The purpose of these gag orders is typically to prevent either the defense or the prosecution from using the media to sway public opinion to their side before a jury is selected—or “taint the jury pool.” A judge, for example, may issue a gag order to prevent the prosecution from releasing evidence to the press that is inadmissible at trial—like a confession or a failed polygraph test. He or she could also prevent the defense attorneys from holding press conferences to cast doubt on the integrity of the prosecution’s evidence. The point is to have a fair trial.

Less typical, however, is for a gag order to be directed at the defendant—and a defendant running for public office no less. A judge tried it in 1987, attempting to prevent Rep. Harold Ford Sr.—who had been charged with fraud—from “sharing his opinion of or discussing facts of the case.” But before long, an appellate court lifted the order, holding that it “unfairly prevent[ed] him from responding to attacks from his political opponents and block[ed] his constituents from hearing the ‘views of their congressman on this issue of undoubted public importance.’” Lower courts have upheld some gag orders despite their First Amendment implications, but those orders have been narrow and deemed necessary to the fair administration of justice.

Chutkan’s order bars Trump from attacking witnesses and specific prosecutors in the trial, but it does allow Trump to criticize President Biden and the Justice Department as a whole to claim his criminal prosecutions are politically motivated. Trump is also allowed to attack Mike Pence—his former vice president and current rival for the GOP nomination—“as long as the attacks [do] not touch on Mr. Pence’s role in the criminal prosecution.”

Trump called the order “unconstitutional” and has said he will appeal, but Chutkan held that “First Amendment protections yield to the administration of justice and to the protection of witnesses.” Trump’s presidential candidacy, she continued, “does not give him carte blanche to vilify … public servants who are simply doing their job.”

Chutkan’s order—which came in response to a request from Special Counsel Jack Smith—seems to be driven less by concerns about tainting the jury pool than worries about witness intimidation. But as Trump’s legal team has argued, it’s difficult to say Trump is intimidating witnesses from testifying when several of those potential witnesses have written books—or launched presidential campaigns, in Pence’s case—criticizing the former president for the actions with which he is being charged. It’s illegal to tamper with witnesses, of course, but gag orders are not an end-around when there isn’t enough evidence to bring witness tampering charges against a defendant.

So given all that, is this order against Trump likely to survive? It’s hard to say. Appellate judges certainly like to defer to trial judges on how they run their courtrooms. But this gag order does seem unusually broad—and all the more so because it involves presidential candidates in the heat of a primary campaign.

Verbatim

Here’s a bit from the gag order itself, which helps demonstrate why Trump is a defense attorney’s worst nightmare:

Since his indictment, and even after the government filed the instant motion, Defendant has continued to make similar statements attacking individuals involved in the judicial process, including potential witnesses, prosecutors, and court staff. … Defendant has made those statements to national audiences using language communicating not merely that he believes the process to be illegitimate, but also that particular individuals involved in it are liars, or “thugs,” or deserve death.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.