Welcome back to Techne! This week I have been listening to Aphex Twin, the nom de plume of producer and artist Richard James. I recently watched this video about the technology that Aphex Twin used to make music. It made me appreciate his work even more.

Why Western North Carolina Spurned Flood Control Measures Decades Ago

The July 17, 1916, edition of The Asheville Citizen could have easily been reprinted late last month and maintained its relevance: “Asheville today is absolutely isolated from the outside world, is a city of darkness void of ordinary transportation facilities, and finds herself helpless in the grasp of the most terrible flood conditions ever known here.”

Both Hurricane Helene and the storm of 1916 moved in from Florida’s Gulf Coast and worked up to North Carolina, inundating the region, which had already been pummeled with rain for days before. In both cases, the French Broad River crested at more than 23 feet, and in both cases, there was widespread flooding, damage, and death.

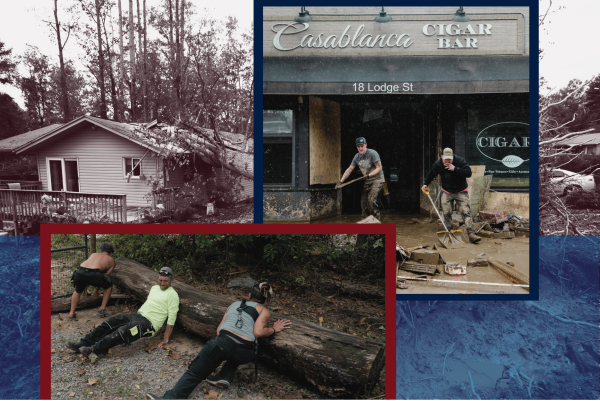

Helene was the deadliest hurricane to hit the U.S. mainland since Katrina in 2005. More than 220 people have died, including 95 in North Carolina. The storm took out essential power infrastructure, with some 370 substations knocked out by the hurricane, and in many places, the infrastructure will have to be entirely rebuilt. Water treatment facilities have been overrun, and homes have been washed away. Lives have been dramatically impacted.

Still, I cannot help but wonder if some of these impacts could have been prevented. Asheville is prone to flooding due to its location on the French Broad River. Major flooding happened in 1916, then again in 1949, in 1961, and in 1964. It happened this year and it is bound to happen again.

The last serious effort to mitigate flooding was stopped in the 1960s by a coalition of land owners and grassroots organizers united as the Upper French Broad Defense Association. Aiding their cause was the newly created National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), a sweeping law I wrote about last month.

Eventually, this group got the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and local authorities to drop the flood plan. But halting the project came with tradeoffs. Without those flood control measures, Asheville remains vulnerable to the same forces of nature that devastated the city in 1916 and again this year.

Today, the work of the Upper French Broad Defense Association is viewed as a significant win for the environmental movement and evidence that environmentalism could unite diverse groups, as recounted in a 2018 article in the journal Environmental History:

Republicans, sharing a common enemy and a genuine concern for the environment, aligned with environmentalists and helped found the Upper French Broad Defense Association. Together, green conservatives and liberals joined forces. They marshaled a local battle with little outside assistance to halt the march of high modernism in the rural Sun Belt.

Given the history, it’s inconceivable to think anyone would want to pick up such a project again. It is simply outside of the political conversation to talk about damming a river to prevent another flood.

Dam opposition.

TVA was established in 1933 as a government-owned corporation under the New Deal. Originally, it was intended to provide general economic development to the region through hydroelectric power generation, flood control, navigation assistance, fertilizer manufacturing, and agricultural development. But since the Depression, it has largely operated as a major power utility and covers parts of Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia.

The French Broad River provides the headwaters for the Tennessee River, so it lies on one of the edges of TVA’s authority. Asheville was built in a bowl that has been carved out of the mountains by the river, so it is especially prone to flooding. In 1961, a major flood devastated the area as rainwater surged beyond the river’s banks. In response, a local planning commission recommended investing in projects that would be built and managed by the TVA to address the flooding issue, protect the area, and improve its economic potential. After another devastating flood just three years later in 1964, the interest in flood countermeasures was reignited.

In 1966, a design was unveiled by TVA: “Located in Buncombe, Henderson, Madison, and Transylvania counties,” as explained in an article in WNC Magazine, “the dams would immerse 19,200 acres under water and create 6,700 acres of lake area and 183 miles of shoreline. The projected cost of the project was $96 million (or $800 million today, adjusting for inflation).”

Initially, civic organizations and government leaders supported the project and in 1967, Congress allocated $3.3 billion to construct the dams. However, opposition quickly mounted, as the plan would flood over 18,000 acres of mostly private land, displacing roughly 60 families.

One of the most vocal critics of the dam proposal was Jere Brittain, whose family’s farmland would have been submerged. Brittain organized a grassroots movement of “dam fighters” who wrote letters, held protests, and demanded public hearings to voice their concerns. The opposition was driven by a combination of environmental concerns, worries about displacement, and skepticism about the TVA’s motives, right as the national environmental movement was kicking off.

In May 1971, the Upper French Broad Defense Association sent a delegation to Washington, D.C , to testify against the TVA proposal. The group’s efforts gained momentum when the recently established NEPA mandated public hearings. The meetings, held in Asheville in August, were heated, with residents donning yellow scarves in protest and voicing their fears about the potential economic and recreational impact of the dams in a 25-hour public comment period.

In the end, the TVA abandoned its plan to build the dams. TVA Chairman Aubrey “Red” Wagner was among those who attributed the decision to the prevalence of local opposition. As he noted in the official announcement, “an assessment today indicated that adequate local support and commitment no longer exists.”

But the decision not to build the dams had consequences. When Helene struck, the flood-prone French Broad River had no major barriers to hold back its waters. While we truly don’t know what would have happened, the dam system that was never built was intended to deal with this type of event.

While it is far from perfect, TVA has repeatedly proven its ability to manage large-scale flooding events. In 2020, Tennessee experienced record rainfall, with over 70 inches of rain and intense runoff threatening parts of the state. TVA’s system of dams and reservoirs was able to avert an estimated $1 billion in flood damages by managing water levels and storing excess rainfall in the Watauga and Douglas reservoirs.

This is not an isolated incident. During Hurricane Helene, Tennessee’s flood control infrastructure was tested once again. Though river levels reached historic highs, TVA dams performed as designed, preventing widespread flooding. Darrell Guinn, a TVA official, explained:

Douglas [Dam] is catching a lot of the rain that Ashville saw. Throughout the system though, the dams performed just exactly like they were supposed to. … We stored the maximum amount that we could at Watauga and Douglas. Those are the reservoirs that received the heaviest rainfall from the North Carolina side of things, and so those are the reservoirs that really kinda filled up to capacity.

There was destructive flooding in Tennessee to be sure, and there was loss of life, which is awful. Many reached their absolute limits, but the dams held. Still, the era of dam building is over, so it is unlikely that a massive water management program to mitigate these floods will ever be put into place. Still, I think it is worth considering one theory for why that’s the case.

Has anything changed?

A former professor of mine, Andrew Rojecki, got me thinking about shifts of optimism in political speech. He was intrigued by the lack of discussion about flood management following the tragedy of Hurricane Katrina. Why was there so little coverage of the levee and dam failures, he would ask in class. The result was “Political culture and disaster response: the Great Floods of 1927 and 2005,” a study that compared the flooding in 2005 to a similar storm in 1927.

Rojecki finds that there was a dramatic flip in support over that time period for flood control projects: “two-thirds of press coverage on the aftermath of the 1927 flood was optimistic [for flood control], a near reversal of that in 2005.” Because of “the absence of a vigorous solutions oriented discourse, attention turned to the scope of the damage and fault-finding.” I think we are seeing something similar today. The lack of a “vigorous solutions oriented discourse” means we end up bickering over the fault.

To me, this is the enduring success of the environmental movement: An entire class of solutions are just off the table. The Overton window has been narrowed. We aren’t even talking about dams and flood management. Has anyone seriously proposed revisiting the 1960s TVA project for the French Broad River? I am having a hard time even finding details about the original project. There is a big gap in the discourse, and it is a technical one. Very little of the coverage of Helene’s aftermath that I’ve seen discusses the technical aspects of the flooding and what might be done to limit it in the future.

In theory, I agree with the build more crowd, and with Thomas Hochman’s critique of this agenda, linked below in the Notes and Quotes section. Public policy should focus on building hard infrastructure. But think about what is not being said about Helene: Even now, when a big water management program could be palatable, there’s simply no talk about a flood management system. That’s telling.

Until next week,

🚀 Will

Notes and Quotes

- For the first time in history, SpaceX returned a space launch vehicle to its launch mount after liftoff. The company successfully recaptured Starship, the world's largest rocket at 400 feet tall, using the launch tower's metal arms. Doing this in the future will save time getting the massive launcher back where it needs to be before another launch, paving the way for quicker, more efficient missions.

- The Nobel Prize in Economics has been awarded to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson “for studies of how institutions are formed and affect prosperity.” For the past couple of years, the Nobel Committee has provided a technical companion giving an overview of the laureates’ work: “First, Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson have made significant progress in the methodologically complex and empirically difficult task of quantitatively assessing the importance of institutions for prosperity. Second, their theoretical work has also significantly advanced the study of why and when political institutions change. Their contributions thus entail substantive answers as well as novel methods of analysis.”

- Thomas Hochman at the Foundation for American Innovation wonders if the abundance agenda has the right political coalition behind it.

- The Department of Justice (DOJ) has proposed remedies in its antitrust case against Google, which I detailed previously in Techne. Adam Kovacevich, founder and CEO of the Chamber of Progress, outlines the feasibility of some of the DOJ’s proposed remedies.

- A federal court ordered Google to open its Play Store and banned Google from entering revenue sharing agreements with app developers. Is this good? Mario Zuniga has a thread.

- The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has issued final rules on pre-merger reporting and notification under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act (also known as HSR). FTC Commissioner Melissa Holyoak explained, “It does not align exactly with my preferences but is a dramatic improvement over the proposed rules.”

- A cyberattack that targeted U.S. broadband provider networks, including Verizon Communications, AT&T, and Lumen Technologies, potentially accessed sensitive information from systems used for court-authorized wiretapping requests. The security breach was tied to the Chinese hacking group Salt Typhoon.

- The U.S. tech sector has no comparison in Europe.

AI Roundup

- California Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed Senate Bill 1047.

- In a bid to secure energy for data centers, Google announced the world’s first corporate agreement to purchase nuclear energy from a suite of small modular reactors, which will be developed by Kairos Power.

- Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, lays out ideas on how AI might transform our world for the better.

- Policy wonks Neil Chilson and Adam Thierer offer a sensible approach to AI regulation in the states.

- In August 2021, Daniel Kokotajlo, formerly of the governance team at OpenAI, wrote an “AI timeline” predicting the state of AI until 2026, and it looks pretty accurate.

- Geoffrey Hinton, known as the “godfather of AI,” just won a Nobel prize in physics.

- My American Enterprise Institute colleague John Bailey alerted me to this new National Bureau of Economic Research paper: “The ABC’s of Who Benefits from Working with AI: Ability, Beliefs, and Calibration.”

- Microsoft launched a free 18-module course on GenAI.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.