Kettle Corn

Matthew Yglesias over at Slow Boring had a nice little piece on the ubiquity of “misinformation” across the political spectrum—even though misinformation is often more readily seen as a problem on the right:

Most people really are very poorly informed about politics and policy. A lot of campaign messaging is pretty misleading. A lot of media coverage is sloppy and propagandistic. It’s also true that as a result of education polarization, over the past few cycles, Democrats have mostly done worse with relatively uninformed demographic groups (poor white people, working-class Hispanics) and better with relatively well-informed high-SES whites. This is to say that if you set out to find misinformation among people voting Republican, it’s not hard to do so. But it’s a totally unprincipled inquiry unless you take a systematic look at misinformation, in which case you’ll see it’s hardly confined to Republicans.

He highlights climate change as being the most obvious area for misinformation on the left, but I appreciate his specific callout to the Michael Brown shooting in Ferguson in 2014. David French and I have talked about the two DOJ reports that came out about that event as a prime example of counternarrative information simply not penetrating.

One report found that the Ferguson police department was motivated by revenue generation and that “many officers appear to see some residents, especially those who live in Ferguson’s predominantly African American neighborhoods, less as constituents to be protected than as potential offenders and sources of revenue.” It also found that “supervisors and leadership do too little to ensure that officers act in accordance with law and policy, and rarely respond meaningfully to civilian complaints of officer misconduct.” Not great, Bob.

But the other report found that there was no evidence to substantiate the claims that Michael Brown had his hands up and was saying “hands up, don’t shoot.” In fact, that report found that “the physical evidence suggested that Brown reached into Wilson’s car during their physical altercation and, very likely, attempted to grab the officer’s gun. … All this was corroborated by bruising on Wilson’s jaw and scratches on his neck, the presence of Brown’s DNA on Wilson’s collar, shirt, and pants, and Wilson’s DNA on Brown’s palm.”

I don’t know whether I’d call the “hands up, don’t shoot” narrative misinformation. It is, but “misinformation” as we have all been using it implies a certain willfulness. In fact, most people just believe something that turned out later not to be true, and they never got the new information. We’ve seen this play out a thousand times—an initial, salacious tweet gets 50,000 retweets and the more accurate, updated tweet gets 23. You’d be forgiven if you never saw the corrected tweet.

But it also elides an important part of the misinformation conversation. The reason the corrected information didn’t get any traction is because it didn’t touch that same nerve and motivate action. I’ve talked about this in the small-dollar donor context. “I’ve got a 37-point plan to fix Social Security” is unlikely to get the cash rolling in the door. “Look at this BAD PERSON who is trying to shut down your church and take your guns” is. Why? Anger, fear, and outrage motivate. Nuance and deep breaths rarely do.

Michael Brown was killed on August 9, 2014. The Department of Justice didn’t release its reports until March 4, 2015. “Hands up, don’t shoot’ is a short phrase everyone can understand. The Department of Justice reports total 191 pages, and no single narrative emerges. The police department as a whole acted badly at times, but that individual police officer didn’t.

And that’s the dynamic that allows misinformation of the type we’re talking about here to continue without being checked.

So what’s the remedy? Clearly, we haven’t found one yet. But I’d start by not using the word misinformation anymore. In my view, it's a breaking news bias where we are all absorbing so much so quickly about what is going on in the world and rarely revisit the thing we “learned” last week.

The other thing I try to remember is that very few people are genuinely evil and even fewer believe they are the bad guys. (Note: Some are and they tend to eat people.) So when you see a story in which there are very clear good guys and bad guys, it’s worth taking a moment to wonder what might be missing. Like all of us, the bad guys are probably the good guys in their own story, so what do they know—or think they know—that we don’t?

That all being said, this can lead to its own form of bias. I often discount stories in the moment that turn out to be true or wait a long time to weigh in on breaking news until we’ve got more facts only to find that outrage was in fact warranted.

Life isn’t a courtroom where we can all wait for all the facts to come out six months later in a 200-page report. What do you think motivated the need for the report in the first place? There’s a reason that we are biologically programmed to react positively to anger, fear, and outrage. It has been of evolutionary benefit to our ancestors.

So where does that leave me? Heading into a summer of election coverage trying to be more thoughtful about misinformation, including the kind I am most likely to fall for—when it turns out the initial reports were true.

Hot Dog With Mustard. Because Ketchup Is Gross.

And this brings me to another piece that a smart person wrote that is rattling around in my head. Patrick Ruffini over at Echelon Insights took a deep dive into the GOP primary swing voters. I’ve been saying for a long time that there is no path to the Republican nomination with only voters who don’t like Donald Trump. Ron DeSantis’ people know this. When I talk to them, every bit of their Iowa-to-New Hampshire strategy comes down to picking away Trump voters from Trump. But which voters are ripe for picking? Here’s Ruffini:

If the race does ultimately boil down to Trump vs. DeSantis, the pivotal voters will be the most conservative ones in the GOP. In other words, don’t expect the party to become friendlier to suburban moderates, at least not until the general election starts in earnest.

I’ve got questions on what it means to be the “most conservative” at this point—especially when pollsters tend to ask voters to describe themselves. There’s a tail wagging the dog aspect to that description. Maybe the “most conservative” voters describe themselves that way because that’s how they like to see themselves. To put it another way, if Trump suddenly came out as pro-choice, pro-spending, and pro-big government and told his voters that they are the ultra conservatives, we’d expect polls to show that the most conservative voters all are voting for Trump, but the term “most conservative” would have lost all meaning.

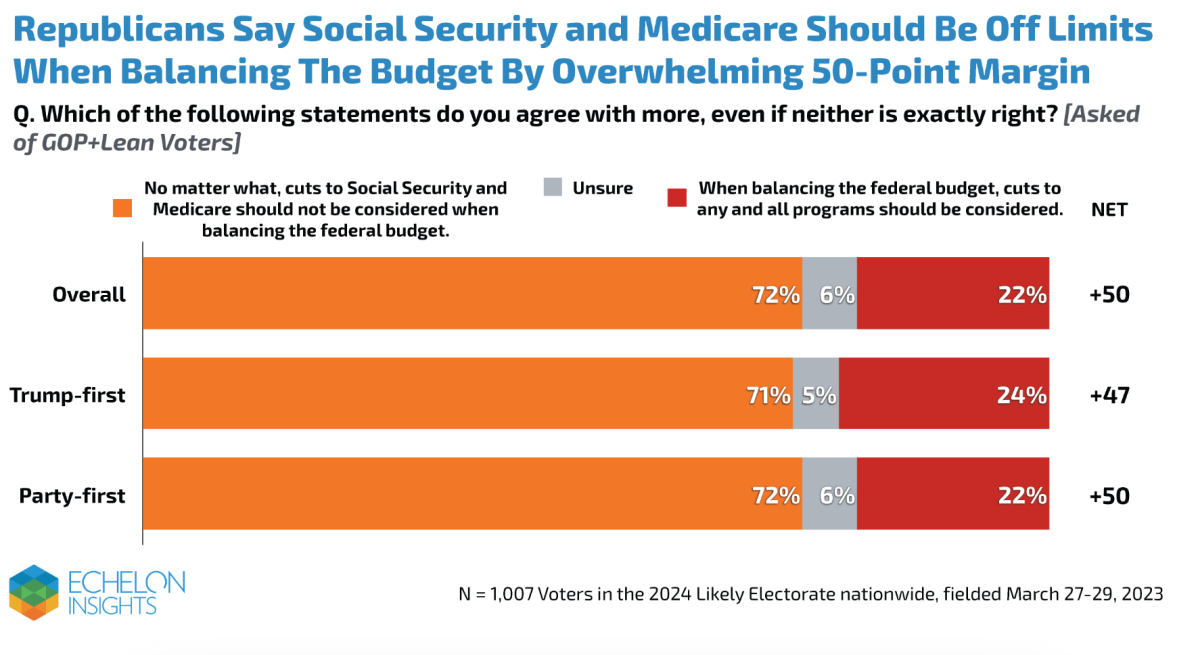

Indeed, Echelon has looked into this problem and found—not surprisingly—that the GOP is shifting. Take entitlement reform. The orange represents the “new” GOP position and the red represents the “old” GOP position. So when voters describe themselves as “very conservative” do they mean under the old definition or the new one?

What’s also interesting here is that there isn’t much of a distinction between “MAGA” voters—the ones who say they are first and foremost Trump supporters—and GOP voters—who say they are first and foremost Republicans. This lends at least some support to the idea that Trump didn’t remake the Republican Party but that Trump effectively tapped into a shift that was already happening within the GOP that other elected Republicans didn’t fully appreciate.

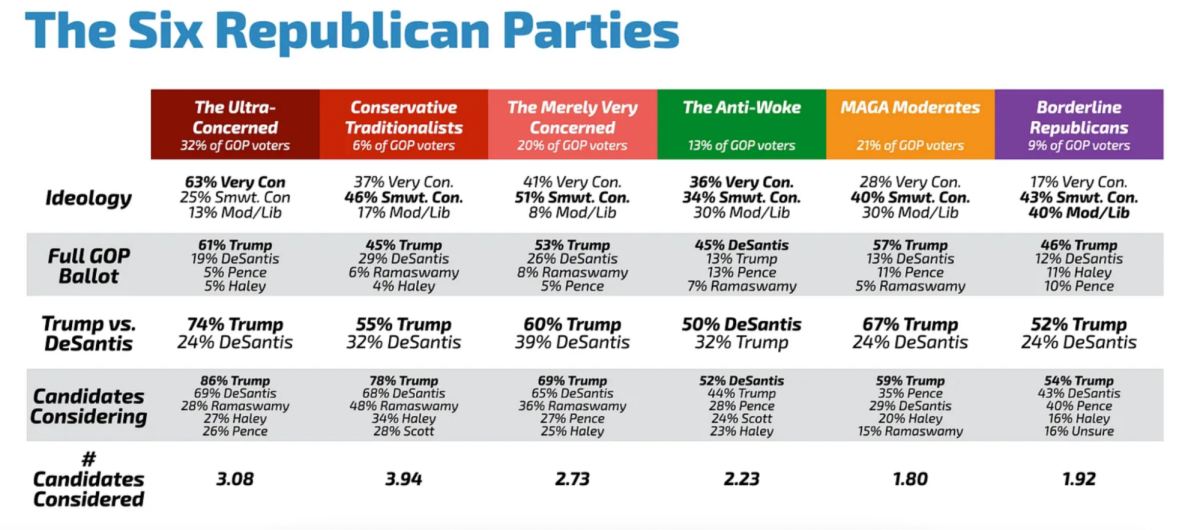

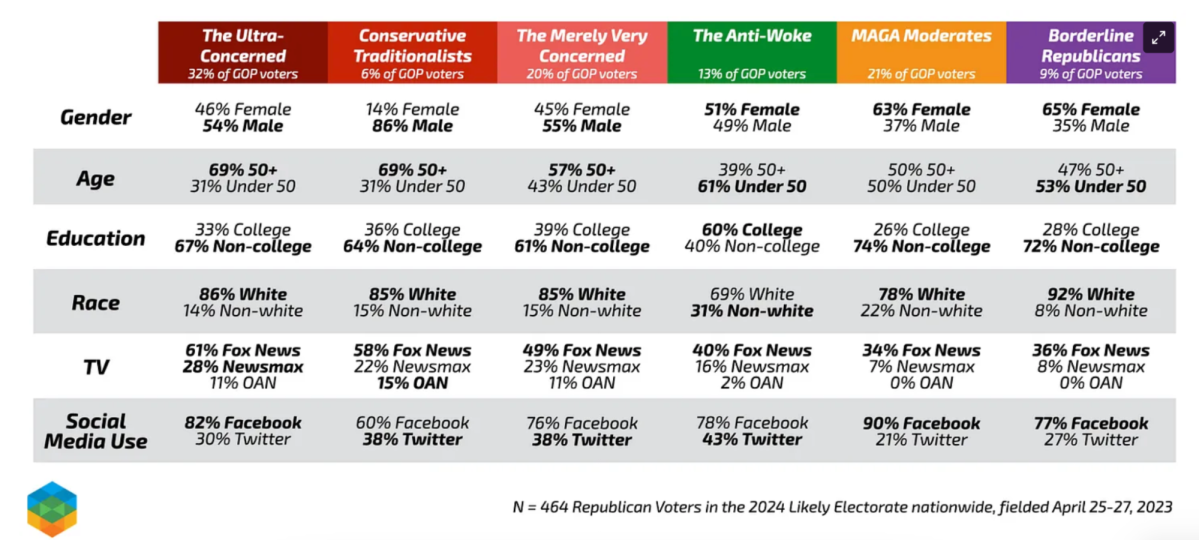

But we digress from our mission of identifying GOP primary swing voters. Here are Ruffini’s six categories:

Let’s say you’re a DeSantis operative. Which of these groups do you focus your attention on?

So first of all, check out the green “anti-woke” group. They’re 13 percent of the primary electorate, they’re the biggest contingent on Twitter, and they’re the only group that currently is going for DeSantis. Wondering why DeSantis did that whole announcement on Twitter? Here’s a good peek into why. There is no path without holding onto what he’s already got.

But he needs more. So who is next?

You might be tempted by the “conservative traditionalists” or the “borderline Republicans.” Trump’s support is lowest in those groups so maybe they are more apt to conversion. But they’re both very, very small—6 percent and 9 percent respectively. It’s not clear the borderline conservatives will even show up to vote and the conservative traditionalists who break from Trump look just as likely to fracture toward Haley or Pence as DeSantis. I’d pass.

Ruffini thinks the “ultra-concerned” are where it’s at. They make up the largest group and are clearly very engaged/outraged about everything, meaning they should be pretty easy to reach on any given issue. Two-thirds are still considering DeSantis even if Trump is their first choice right now. It’s a target-rich environment and there’s probably some ways to slice that group up into some smaller subsegments that could be even more fruitful.

But I’m also interested in the “merely very concerned.” Here’s how Ruffini describes them:

Trump and DeSantis post nearly identical consideration scores (69% and 65%) but Trump has a two-to-one lead on the ballot. Ramaswamy posts his highest ballot support in this group, at 8%.

Here’s what I like about this group: They’re looking at both DeSantis and Trump in equal numbers, but Trump is way in the lead. Why? And they’re clearly still shopping for something different if Ramaswamy is pulling 8 percent. Interestingly, they are disproportionately less interested in the CRT stuff. I’d definitely want to get a focus group together to understand why that is. But I like that demographically it looks like my green, “anti-woke" stronghold—lots of women and skewing a little bit younger. The big difference is that my green stronghold is largely college educated and this group is flipped. But at 20 percent of the party, I can move some numbers if I focus my fire here and learn to tailor my message to a non-college educated audience.

Watermelon

Speaking of rage-inducing, a few years ago I read the book, Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men. The author is clearly a hardcore feminist of the old school variety. That would have put her to the far left a couple decades ago, but today … perhaps not. The book radicalized me in any number of respects, but then I saw this over the weekend:

The crash tests that regulators use to rate vehicles’ safety don’t use female test dummies in the driver’s seat in a key test, and in the tests where they are used, the dummies are less-accurate, scaled-down male versions. Advocates say the discrepancy means that hundreds of women needlessly die in crashes every year.

STILL!?!?!?!??!!?

Women are 73 percent more likely to be injured—and 17 percent more likely to die—in car crashes. We’ve known this for decades. And the reason is very simple—the damn things aren’t designed for our safety because nobody bothered to think about our safety. And that’s not even thinking about the millions of pregnant women driving cars out there where we know the car isn’t made to protect either one of us in the driver’s seat.

In almost all areas of scientific study, men are the default and women are the other. We design cars and drugs and public safety announcements about heart attacks for the default.

Why do we bother having women in Congress if we can’t get this very small, very obvious thing fixed?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.