Side Salad

Statistics are easily manipulated. So when it comes to my brand of feminism, I’ve rejected measuring equality by things like “the wage gap.” Instead, I will believe that women have achieved par when three things are true: Average office temperatures are above 72 degrees, half of the passengers in first class on airplanes are women, and tampons can be found in every public restroom. I also believe that if men were charged with carrying babies, we would have invented a laundry machine-sized gestational pod before we landed on the moon.

But what does any of this have to do with politics? Because there’s lots of reasons to think women will be overtaking men economically and professionally in short order. The fact that women are 60 percent of college graduates kinda tells you everything you need to know about where this is all headed. Finally! Affirmative action for white men!

But what will this mean for voting behavior and the gender gap? Maybe not much at all. Check this out:

In short, all things being equal, all things aren’t equal. Women don’t do housework because they’re stay at home moms or because husbands work longer hours. They do it because … they’re women. There’s lots of non-sexist reasons why this could be the case. The most obvious to me is that the person who cares whether there are dirty dishes in the sink is more likely to clean the dirty dishes in the sink. Men are, on average, more disgusting than women, therefore women are more likely to be motivated to keep their home tidy. I can think of plenty of sexist reasons too.

Which is all to say—I don’t expect the gender gap to decrease as women take over the industries that were traditionally male-dominated and start outearning their male counterparts. If anything, we might see the gender gap increase because women’s preferences are largely unrelated to their earnings but as they earn more they may be able to express those preferences more strongly within the political economy.

A Large Pizza

There are a lot of frog-in-boiling-water phenomena in politics in which the sudden or immediate distracts us from the slow-moving trends that will actually shape our politics for the decades to come.

As Jonathan Kennedy argues in his new book Pathogenesis, a lot of major world events are more attributable to pathogens than to human causes. American Revolution? Sure, that Declaration of Independence was nice and George Washington was a good guy, but the real reason America came out on top was … malaria! (The book goes into greater detail, but in short British troops had no immune protection from pathogens in the southern colonies so were disproportionately killed off—not to mention the effect on morale.)

I’ve often talked about Trump in these terms. It’s easy to get caught up in the hour-by-hour news cycle of Trump outrage and Trump voters to find causes like a fractured 2016 GOP field, Trump’s universal name ID, angst over increases in illegal immigration, culture war fights over wokeness, etc. But when I step back, those are probably better classified as symptoms.

Any explanation that seeks to account for Trump and Trumpism also has to explain why we’ve seen similar nationalist/populist movements in so many other Western democracies all popping up at the same time. I think the answer to that is pretty clearly the continued fallout from the 2008 financial crisis—a worldwide phenomenon that pitted the elites (by income but also often by education) against a working class that had more often been aligned with the liberal parties (think Labor Party and Democrats, for starters). When you start from there, some form of Trumpism—at least—was inevitable.

Of course, America had unique political causes as well. Top of my list, of course, is weakened political parties that can no longer maintain control over their standard bearers. That in turn was caused by (or at least accelerated by) campaign finance reform that gutted the main power source of the modern parties—access to money and large-dollar donors with money—and empowered candidates who could maximize their share of small dollar donors, which in turn incentivized simpler, more outrage-inducing messaging.

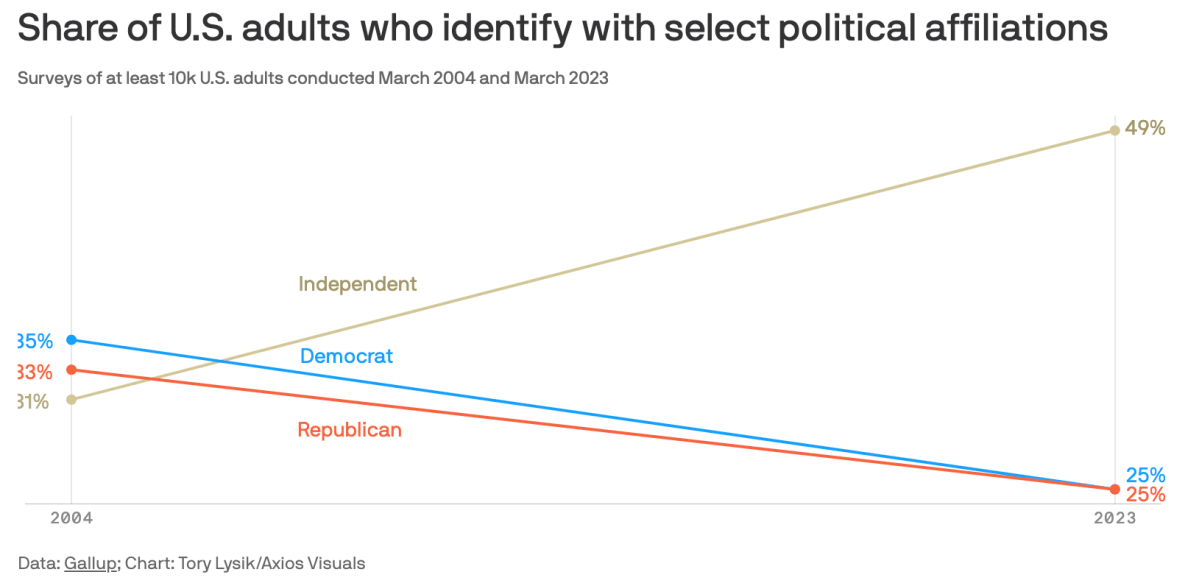

But I digress. My point is that, proportionally speaking, we spend way too much time talking about the president’s approval numbers or the head-to-head polling between DeSantis and Trump and not nearly enough time talking about this:

This trend has been relatively constant over the last 20 years. Every year, more people disaffiliate from the major political parties and are left wandering the earth as a remnant of their own sort. I’d venture to say nearly everyone reading this newsletter identifies with this phenomena to some extent. I’d also argue that 49 percent isn’t a remnant anymore. It’s a plurality and next year will be the majority of voters. But this raises all sorts of questions and problems both in the short term and the long term.

First, it’s not that this 49 percent is some huge chunk of moderate voters. They’re all over the place politically. In fact, as these voters have left the two major parties, their voting behavior hasn’t actually changed. So what’s going on? For a lot, they’re embracing the tribalism of parties without wanting a leader of the tribe. Think about the people who attack the “GOP establishment.” They’re often talking about the Republican National Committee—or its perceived allies. This further weakens the parties as they try to hold on to these voters by chasing them instead of controlling the levers of power that attract people to a party structure in the first place.

Second, look at that 25 percent that is left working within the party structure. It’s a well-studied phenomenon that groups of like-minded people end up taking more extreme positions than the average like-minded individual acting alone. Why? As one set of researchers helpfully put it: “A fundamental problem with political discussion in groups of like-minded individuals is that the ideas and opinions that thrive within this context escape reasonable criticism based on other points of view. Hence, such groups may end up with extreme, or at least very narrow, views.”

Political parties, then, that represent large swaths of people with varying attachment to—and sometimes contradictory—policy positions are going to have trouble polarizing themselves. But as we shrink the group down to the voters that feel the most attachment to and benefit from the party, it’s easy to see how each party will become more extreme over time.

And indeed … they have.

Americans surveyed believe both parties are now equally “extreme.” And Pew Research Center now finds that “Democrats and Republicans are farther apart ideologically today than at any time in the past 50 years.” Here’s a helpful visualization:

And what strikes me most about all of this is that it’s not clear which factor is driving which. Causal possibility 1: The parties became more extreme because extremism helped boost turnout among higher likelihood voters in the base. The people who felt left out left. And the result was that they left behind a higher percentage of like-minded people, driving the parties to become more extreme. Causal possibility 2: People left the parties as they became weaker and felt less relevant. The smaller group tended to be more committed to party politics and more likely to want to be like-minded. That resulted in more extreme policies, which pushed more people out.

Regardless of which explanation you think is more likely, it doesn’t matter because once the cycle starts, it’s hard to see what internal forces will stop it.

Third, and most glaring to me, half of American voters may no longer identify as R or D, but 84 percent of congressional races were decided by more than 10 points, which means they were decided in the partisan primary that these people feel no attachment to and in some states would be barred from participating in. As a result, we’d expect the two candidates in general elections to be less and less representative of their constituents. As we discussed above, this will drive Congress further to the extremes. But it also could alienate more people from voting at all. Except we’ve seen the exact opposite in recent cycles—voter turnout in general elections has been sky high. Why? Because that 49 percent may not want to identify with either political party but they also believe that one of the two “extremists” is an existential threat to their way of life. Yikes!

Fourth, and this is the one you’ve all been waiting for, doesn’t this mean there’s an eager audience for a zillion third parties—or even just one? Eh. I’m not convinced. Like I said, there’s not a lot of evidence that those in the 49 percent agree on much of anything. And the two-party system is hard to disrupt because they constantly work toward equilibrium. Ie as soon as one party loses ground to its rival, it changes course to get back to 50 percent and if a potential third party pops up, the party most threatened by it will try to absorb its most attractive qualities. This is how the two political parties have morphed so dramatically from, say, their policy positions at the turn of the century … or even the 1950s.

Plus there’s the history. There’s really been only one successful third party in the United States since the two-party system solidified: the Republicans. And that party had the distinct advantage over other third parties because the actual party it was replacing—the Whigs—had already ceased to exist. It also helped that shortly after the dissolution of the Whigs, incumbent Democratic President James Buchanan decided to break his own party in two, which meant that one of the Whig babies was in a prime position to win the presidency.* So in the four-way race of 1860, a third party won and that party has been one of the two major political parties ever since.

(There’s also a decent argument—one that I’m admittedly partial to—that the Republican Party was never a third party and was always just the largest splinter of the Whig Party destined to reconstitute itself in some form around the issue of slavery.)

Regardless, it’s not the situation we have today in which both parties, umm, exist and have a stranglehold on ballot access to boot. It’s also relevant, in my view, that there isn’t a policy issue that has become the singular focus of national attention a la slavery that would allow new parties to get a foothold.

But there's certainly a lot of turbulence in and around the two parties these days. Still, I think the current third parties’ focus on presidential politics is a non-starter for me at this point. On the other hand, I’d be very interested in a third party that is focused on local races where I think there’s arguably more room for these types of candidacies.

Milkshake

Some things are true through generations. In fact, many things are.

*Correction, April 18: Because of an editing error, this piece misidentified the president who divided the Democratic Party before the 1860 election. It was James Buchanan, not Franklin Pierce.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.