Dear Reader (Including the Jew-ish among you),

The 11 scariest words in the English language, at least in some very specific circumstances, might be: “Let’s ditch the rules and do something really off the wall.” This is simply not something you’d want to hear from, say, your heart surgeon. I imagine prostitutes don’t want to hear it from their clients, either.

And maybe it’s not something you want to hear from me, either. But there’s nothing you can do to stop me (cue maniacal laugh).

I had a weird idea occur to me while recording The Remnant podcast this morning. I want to make the Marxist case for nuclear fusion. I know what you’re thinking: “Not that dead horse again.” But, as an early draft of Castaway had Tom Hanks saying before they changed his inanimate buddy from a lacrosse stick to a volleyball, “Stick with me.”

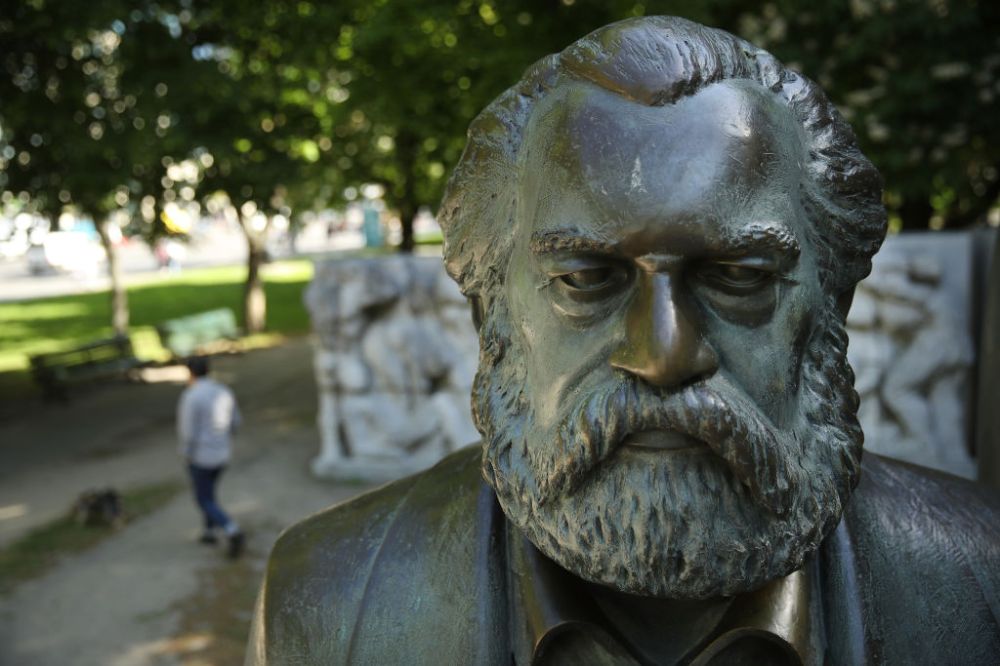

Marx the poet.

I think I’ve established my street cred as an opponent of Marxism. But that doesn’t mean Marx isn’t worth reading.

But let me make a few points up front to dispel any confusion. First, don’t get me wrong. Just because some of Marx’s stuff is very interesting and occasionally very insightful, doesn’t mean I think it’s necessarily correct or persuasive—never mind defensible.

Second, you can buy into vast amounts of Marx’s writing, and still believe that Marxism—i.e. the brand name for authoritarian policies and politics imposed on whole societies—is hot garbage. It’s sort of like how every Christian I know is willing to admit that some of the things done in the name of Jesus (never mind Paul’s!) teachings weren’t very Christian. Right now, there are Russians who insist the answer to “What would Jesus do?” is “Bomb Ukrainian children.”

I’d like to think there are very few sincere Christians who aren’t utterly disgusted by that. So it is with Marx and Marxism (also just to be very, very, clear: Marx was no Jesus). This is something pretty much all the sincere Marxists acknowledge today, in part because if they didn’t, they wouldn’t be able to bore the crap out of everyone at the co-op by shouting “Real Marxism has never been tried!”

Intoxicating ideas can make anybody drunk, but what often happens is that the intoxicant turns out to be insufficient and the idea turns into a mixer of sorts hiding the real high proof stuff: power.

Marx wrote very little on how Communism would actually work, because as Paul Johnson and others argue, Marx was really a frustrated Romantic poet. “The poetic gift manifests itself intermittently in Marx’s pages,” Johnson writes in Intellectuals, “producing some memorable passages. In the sense that he intuited rather than reasoned or calculated, Marx remained a poet to the end.”

This is one of the things that makes Marx interesting to read because it was the poetry, not the analysis, that lit fires in the minds of men.

This was George Sorel’s insight about Marx, that he should be read more as a prophet. He admitted that Das Kapital was pretty worthless as “scientific” analysis, but really useful as “myth.” It should be seen as an “apocalyptic text … as a product of the spirit, as an image created for the purpose of molding consciousness.” Sorel, by the way, was an immense influence on both Lenin and Mussolini.

For all the clever marketing involved in calling his views of history’s unfolding “scientific”—what better way to fend off criticism than to accuse your opponents as science “deniers”—Marx’s vision was apocalyptic and fundamentally religious (even if he claimed to reject religion in all forms). In his 1856 speech commemorating the anniversary of the Chartist People’s Paper, he concluded with a kind of prophecy. He dubbed the “English working men” the new chosen people for his eschatological vision. And why not? History was supposed to make its great leap forward in industrial, capitalist Britain, not in the rural backwater of Russia. These “first-born sons of modern industry” in England would lead in the liberation of their class all around the world. Marx lamented that their struggles had not been showered in the glory they deserved because they had been “shrouded in obscurity, and burked* by the middleclass historian.” But the workers would get their vengeance. On this score he invoked the medieval institution of the Vehmgericht.

To revenge the misdeeds of the ruling class, there existed in the middle ages, in Germany, a secret tribunal, called the “Vehmgericht.” If a red cross was seen marked on a house, people knew that its owner was doomed by the “Vehm.” All the houses of Europe are now marked with the mysterious red cross.

History is the judge—its executioner, the proletarian.

But what would come after the righteous slaughter of the bourgeoisie and the ruling classes, according to Marx? Good times! Specifically, a post-scarcity civilization where you could do pretty much whatever you liked and be whatever you wanted.

You see, one of the things Marx hated the most about capitalism and industrialization—necessary evils according to Marx, by the way—was the specialization of labor. He hated the idea that you had to pick a lane to earn your daily bread. A plumber couldn’t be a poet—at least not if he wanted to make a living. The capitalist system erodes all “human and natural qualities,” he wrote in his Philosophical Manuscripts. It makes workers, "both physically and spiritually de-humanized (entmenschtes),” living in hovels that are worse than pre-modern caves because they were "poisoned by the pestilential breath of civilization.” Marx was like the dorm room loser who insists he could be a great novelist, musician, or inventor—or all three—if only the “system” (or the Man, the globalists, Wall Street, Jews, or Egg Council) didn’t keep him down. He reminds me of Zach Galifinakis in an episode of Between Two Ferns when he said the Jews want to keep him fat (or something like that).

This would all end under true communism. “In place of the old bourgeois society, with its classes and class antagonisms, we shall have an association in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all,” he wrote in the Communist Manifesto.

Or as he put in The German Ideology:

For as soon as the distribution of labour comes into being, each man has a particular, exclusive sphere of activity, which is forced upon him and from which he cannot escape. He is a hunter, a fisherman, a herdsman, or a critical critic, and must remain so if he does not want to lose his means of livelihood; while in communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.

Marx put the “commune” in Communism.

Now, a lot of this is warmed over Rousseau. What Marx wants is a return to the bogus idea of the noble savage who, according to Rousseau, lived in relative solitude and peace doing what he pleased when he pleased.

As anthropology, this stuff is trash. And as economic prescription, the idea that humans—remember all humans—could live the way he imagined humans did in the past, this is more like science fiction.

Star Trek economics.

Which brings me to fusion.

Among the fundamental problems with Marxist economics is an inability to deal with the problem of scarcity. If the market isn’t allowed to work its magic at figuring out how to allocate resources by using prices and profit, it has to fall to something, i.e. someone, else to do it. That’s why you need a party and a bureaucracy to figure out who gets toilet paper and who gets back issues of Pravda. Marxists are hardly alone in believing that planners, experts, and social engineers should—and can!—figure out the best way to distribute finite resources. But Marxists went the farthest with it.

But what if the problems of scarcity can be “solved” not by planners but by technology and entrepreneurs?

I’ve never really understood the economics of Star Trek, but it always seemed to me that they weren’t as nonsensical as they seemed given that they’d invented the “replicator.” This was a doohickey that used the same technology as the transporter to rearrange molecules to make just about anything, including food and clothing. It was a perfected form of 3D printing.

Physical space was also no longer an impediment. In a universe where there are an infinite number of habitable planets, there’s real estate for everyone. Of course, all of this is only possible when you have enough energy to get where you want and replicate the materials and food you need. I’m not saying that the economics—or politics—of Star Trek actually make sense. I’m just saying they’re not as crazy as they seem. When the means of production have been truly democratized, who the hell knows what political economy would look like?

And that’s why I think Marxists—and more generic leftists—should be stoked about fusion. Yeah, it’ll be a long time before it’s commercially viable at scale, but if and when it is, all sorts of impossibilities become possible. (Jim Pethokoukis has a great primer on the state of play in Fusion World.)

There’s a rich tradition of Marxist/leftist/Green hostility to the idea of limitless, cheap, energy. Cheap energy fueled industrialization, deforestation, and all sorts of things that are at war with a “sustainable” environment. The environmental left hated oil because it was the lifeblood of capitalism before they hated it because of climate change.

But cheap energy could also fix a lot of the problems—“externalities”—that the era of fossil fuels created. Fossil fuels would be relatively easy to phase out. Hydroelectric dams, environmentally gruesome edifices, could be torn down. All of the hideous solar and wind farms could also be mothballed, returning all of that land to nature or more productive uses. Desalination is crazy expensive in part because it’s so energy intensive. Fusion could solve that. Heck, it’d be crazy to try and scrub meaningful amounts of CO2 from the atmosphere with existing technology. But maybe with inexhaustible supplies of cheap energy it wouldn’t be? I’m not sold on genetically engineered meat yet, but it seems to me you could come up with some nifty stuff at scale with limitless energy supplies. Say goodbye to factory farming.

Of course, cheap energy wouldn’t solve every problem, and it would undoubtedly create some new ones. But that’s true of every new form of energy. The question is whether the problems the new forms of energy creates are better problems than the old ones.

More broadly, while I hate most of the “metaverse” stuff, if I were of a Marxist or hyper environmentalist bent, I’d be pretty psyched by its potential to keep people from using up natural resources. More to the point, in the physical world we can’t all be the Renaissance men that Marx envisioned, but in the virtual world? Why not? There’s a hell of a lot of scarcity in meatspace: a finite number of trees to make your cabin and a finite number of Walden Ponds to put them on. But in the virtual world? You can be as much of a hermit or socialite as you like. I don’t want to be a herdsman, hunter, and critic the way Marx did. But if that floats your boat, plug into the Zuckerverse and knock yourself out.

We’re already in the opening chapter of the Dematerialization Era. As my friend Jonathan Adler writes:

What is now being observed represents a fundamental decoupling of resource consumption from economic growth, such that as mature economies grow, they not only use fewer resources per unit of output, but they also consume fewer resources overall. In short, economic growth in the most developed nations increasingly coincides with a net reduction in resource consumption. The United States in particular is “post-peak in its exploitation of the earth,” according to Andrew McAfee in More from Less: The Surprising Story of How We Learned to Prosper Using Fewer Resources — and What Happens Next

Dematerialization is a fancy way of saying that scarcity may no longer be the iron cage it once was. I suspect there will always be scarcity of some sort, not least the scarcity of human attention and time.

But what I’m getting at is that because of the Marxists’ hostility to markets and all that comes with them, they might be missing the only viable route to the Heaven on Earth the Marxists promised but couldn’t deliver.

Marxist economics is a boneheaded way to structure an economy precisely because it fails utterly to confront the problems of scarcity and the benefits of innovation. It pretends to be a “productivist” ideology but it sucks at producing the stuff normal people want, like wealth and improved living standards. Yeah, yeah, the Soviet Union delivered on this score for a while because they imposed technological advances—like replacing ox-carts with tractors— but they did that by using Western technology and killed a lot of folks in the process. And yes, the Chinese Communist Party lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty, but they did that only by embracing markets and trade.

We’ll never get to the immanentized eschaton Marx envisioned, but the great irony is that we can get much, much, closer to it thanks to capitalism. In Henry Adams’ autobiography he has a chapter titled “The Virgin and the Dynamo,” in which he postulates that the Dynamo, i.e. technology, had replaced the Virgin, traditional Christian religious notions, as the organizing passion of Americans. In effect, he was saying that “engineering,” broadly understood, was the new religion, an idea that in the Progressive Era (and perhaps today) seemed to be proven true. There’s a lot that can be said about that, but I’m running very long. Still, it does provide a nice opportunity to bring up, again, my favorite quote by Eric Voegelin:

When God is invisible behind the world, the contents of the world will become new gods; when the symbols of transcendent religiosity are banned, new symbols develop from the inner-worldly language of science to take their place. Like the Christian ecclesia, the inner-worldly community has its apocalypse too; yet the new apocalyptics insist that the symbols they create are scientific judgements.

But what I want to leave you with is the profound irony that the system Marxists and environmentalists so despise may not be what stands between them and the egalitarian romantic nirvana they yearn for but the best, and probably only, means of delivering it. Whether we should want to live in that nirvana is a subject for another time.

Various & Sundry

Way back at the beginning of this “news”letter, I put an asterisk after the word “burked.” I did that because I wanted to offer a definition but I didn’t want to break the flow. Burke is an awesome word I had forgotten. It means: “to murder, as by suffocation, so as to leave no or few marks of violence” or “to suppress or get rid of by some indirect maneuver.” So you might say, the best assassins burke their victims.

Canine update: We got very good news about Zoë. Her lipoma isn’t cancerous. We didn’t think it was, but the vets were also very concerned that it might be “intrusive” given its size and location. Intrusive lipomas can send nasty tendrils into organs. But that’s not happening. She took a while to recover from the stress of the vet and, weirdly, Pippa saw this as an opportunity to express her spaniel rage, snarling at Zoë to stay away from her and food she wanted. It’s all so strange because Pippa has been, and remains 99.9 percent of the time, the world’s most harmless dog. Heck she’s even willing to share her food and water station with Gracie, something Zoë would never do. So it’s just weird to see her get all chesty. I have no good explanation for it. Other than that, all the beasts are very happy.

ICYMI

And now, the weird stuff

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.