Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

You’re reading the G-File, Jonah Goldberg’s biweekly newsletter on politics and culture. To unlock the full version, become a Dispatch member today.

Hey,

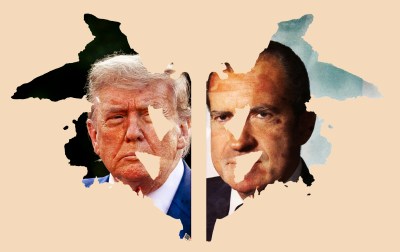

A few years ago, Charlie Cooke made a really good point (as is his wont) about how post-Trump Republican politics would work. Republican candidates would borrow a page from Ronald Reagan. In the 1970s, Reagan didn’t attack Richard Nixon on Watergate. He just avoided, as much as possible, talking about the then-recent unpleasantness because it divided the GOP coalition.

The relevance of Charlie’s observation at the time was that people were expecting too much of Republican politicians if they wanted them to forcefully denounce or repudiate the former president. It may not speak well of politicians generally, and it is certainly unsatisfying for critics of Donald Trump, never mind full-blown resistance types, but given Trump’s popularity with segments of the GOP, the wisest course of action for future presidential aspirants would be to leave most of the hard-hitting criticism to others.

Richard M. who?

I bring this up because I think the observation taps into a broader phenomenon: the giant Nixon-shaped memory hole on the right. If you have any memories of the 1970s or ’80s, the claim that nobody talked bad about Nixon might seem strange. But by this I mean the whole Nixon, not the Nixon of All The President’s Men and all those other books about the Watergate scandal.

Obviously, Watergate was a big deal. It ratified so many of the left’s obsessions, none more so than heroic narratives about journalism. It also vindicated people who hated Nixon for his anti-Communist crusades and his campaign against Helen Gahagan Douglas. It also vindicated more mainstream Democratic partisans who held onto their hatred of Nixon from the 1960 campaign.

Vietnam was the other major factor. Nixon pulled us out of Vietnam, but the way he did it infuriated opponents of the war (and many supporters!). “Vietnamization” and the bombing of Cambodia were not what the antiwar crowd had in mind. The eventual fall of Saigon was not what the pro-war crowd had in mind. But given the politics and the exhaustion with the Vietnam war, much of Nixon’s legacy got folded into a Fawlty Towers-esque “don’t mention the war” tendency.

But the most under-appreciated reason both Democrats and Republicans alike avoided a clear-eyed appraisal of Nixon: Nixon was a “me-too Republican.”

The first ‘me too.’

Forgive me for offering a little remedial political history for the young’uns and otherwise uninitiated.

The modern conservative movement was born in the wake of the New Deal. It should have been born in reaction to the Woodrow Wilson administration, but for complicated reasons, it wasn’t.

The main target of conservative ire—other than Communists—were so-called “me-too Republicans” (later dubbed “Modern Republicans” and then “Republicans in Name Only” or RINOs). These were Republicans who said “me too” to the monumental changes wrought by Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal.

Robert Taft’s forces at the 1952 Republican Convention handed out badges and pamphlets reading “No Me-Too in 1952.” Taft lost the presidential nomination to Dwight Eisenhower, who famously made the New Deal bipartisan by refusing to undo it. Conservative opposition (some of it ill-considered) to Eisenhower’s me-too-ism became the rallying cry of movement conservatives. When Barry Goldwater was asked what kind of Republican he was, he replied “not a me-too Republican.”

A message from The Dispatch

Read The Morning Dispatch Free

We’re taking our flagship newsletter out from behind the paywall this week. If you’re looking for a greater understanding of the biggest stories shaping your world, give The Morning Dispatch a try for free—because insights beat outrage.

You are receiving the free, truncated version of The G-File. To read Jonah’s full newsletter—and unlock all of our stories, podcasts, and community benefits—join The Dispatch as a paying member.

Stories We Think You’ll Like

Trump Is Nixon 2.0

And DOGE is like CREEP, but on steroids.

Vance, Without Illusions

The vice president’s continued ascent has a lot of obstacles.

A Disgraced President and America’s Pastime

How Richard Nixon headed off an umpires’ strike 40 years ago.

But, hold on—I should back up even further. When I first heard the epithet “me-too Republican,” I was in high school. I took it to mean “Rockefeller Republican” or some such. And in those days that’s basically what it meant: squishy, country club, establishment. But that’s not how it started. It was a far more a red-meat term, at least for some folks who came of age hating FDR or the Soviet Union or both.

Forget for the moment what you know, or think you know, about “right” and “left” or even Republican and Democrat. In the 1930s, right and left really didn’t have the kind of analytical and descriptive power we give those terms today. There were a lot of Republicans who sound left-wing to the modern ear, and a lot of Democrats who similarly sound right-wing (recall that the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s was essentially the militant wing of the Democratic Party).

In 1936, Missouri Sen. James Reed, the leader of the “Jeffersonian Democrats,” told a crowd of activists that Roosevelt had dragged the Democratic Party “over into Red territory.” He added, “I make the assertion that there isn’t a chemist in the world who could analyze a Russian Bolshevist and analyze the New Deal and tell which was the Bolshevist and which was the New Deal.”

This sort of thing was a hallmark of various populist demagogues. Antisemitic crank and Nazi sympathizer James True led an organization dedicated to fighting “the Jew Communism which the New Deal is trying to force on America.” Gerald L.K. Smith argued that the “New Deal is Communism in disguise.” “There can only be one Capitol, Washington or Moscow… ” he insisted, “one atmosphere of government, the clear … air of free America, or the foul breath of Communistic Russia.” Father Charles Coughlin initially supported the New Deal as “Christ’s Deal” and campaigned in 1932 for FDR, vowing that it was “Roosevelt or Ruin.” A few years later, Coughlin broke with Roosevelt. At a rally of 25,000 people, he proclaimed that “[t]he old corpses of the Democratic and Republican parties are stinking in our nostrils” and insisted that the New Deal was brimming with “atheists” and “red and pink communists.” The populist Union Party in 1936 was a vehicle for this crowd. Rep. William Lemke, the party’s presidential nominee, told the same rally, “I do not charge that the President of this nation is a Communist,” but he added, I do charge that . . . Communist leaders have laid their cuckoo eggs in his Democratic nest and that he is hatching them.”

In the 1950s, with the Cold War intensifying, there was a lot of retconning about the New Deal, and the idea that it had been a kind of—or actual!—Communist plot gained more and more traction in certain quarters, and not necessarily just on the fringe. The critique morphed more into a foreign policy argument about FDR’s stewardship of World War II, specifically his generous treatment of Joseph Stalin. This made the older argument that the New Deal was a kind of Soviet beachhead even more plausible—and more sinister.

For the record, I don’t find this argument persuasive. Yes, FDR had many Soviet sympathizers and Communist fellow-travelers (and former sympathizers of Fascist Italy) in his administration, most obviously his vice president, Henry Wallace. FDR was wrong about many things, but he was a progressive nationalist, not a Bolshevik.

I bring this up in part because a lot of the commentary about the John Birch Society, and William F. Buckley Jr.’s battles with it, often make it sound like the fever-swamp right somehow sprung up ex nihilo. But the truth is that Robert Welch, the founder of the John Birch Society, was part of a political tradition that predated by decades his claim that Eisenhower was a Communist agent. Indeed, such claims were simply the logical continuation of a narrative that suffused various populist movements in America.

A lot of historians retroactively impose the label “right wing” on all of this. But if you actually look into the backgrounds or policy proposals of these populists and muckrakers, it’s often just as easy and just as defensible to put them on the left. Their lineage can be traced through Huey Long, Father Coughlin, William Jennings Bryan, Edward Bellamy, Ignatius Donnelly, and other figures who were hardly champions of limited government, free markets, or constitutionalism as we understand it. One reason this gets so confusing is that a lot of historians, and contemporary partisans and journalists in the 1930s, simply called any opponent of FDR “right wing” even when—like Coughlin—they substantively attacked Roosevelt from his left. Moreover, as the Cold War intensified, being anti-Communist increasingly became synonymous with being “right wing” for many commentators, even though there were plenty of anti-Communist progressives, like you know, Harry Truman and Arthur Schlesinger.

Joseph McCarthy, who fed off these cultural and political currents, was definitely an anti-Communist and colloquially “right wing,” but he wasn’t exactly a traditional conservative. He was a populist rabble-rouser.

I hope this helps to explain that the charge of being a “me-too Republican” wasn’t just a complaint about being a “moderate” or a “squish.” At the same time, I don’t mean to imply that if you had a problem with the New Deal, you were an antisemite or nutjob. Opposition to the New Deal is an entirely defensible point of view—one I largely subscribe to!—and does not require holding crazy conspiracy theories about Jewish Communists running wild in the White House.

So, let’s get back to our story. When Eisenhower left office, his vice president, Richard Nixon, became the foremost “me-too Republican”, meaning that according to the understanding of the post-WWII political and ideological spectrum, he was a moderate New Deal liberal. Yes, he was an anti-Communist and law-and-order guy. But neither of those things qualified you as a serious right-winger, at least not on the actual right. More on this in a moment.

In 1960, Goldwater was dismayed over the prospect of another me-too-er in the White House. He told his friend, future Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist, “I would rather see the Republicans lose in 1960 fighting for principle,” he wrote in a letter, “than I would care to see us win standing on grounds we know are wrong and on which we will ultimately destroy ourselves.” National Review declined to endorse a presidential candidate in 1960 for similar reasons.

Nixon narrowly lost to John F. Kennedy, and the fight for control of the GOP began in earnest. Conservatives demanded A Choice, Not an Echo, as Phyllis Schlafly put in a pro-Goldwater manifesto. Nixon resented the conservatives—who had once admired his anti-Communist stances in Congress. He told reporters in 1965 that “the Buckleyites” were “a threat to the Republican Party even more menacing than the Birchers” and the biggest “threat to the parties’ rebuilding efforts.” An amusing twist: Nixon dispatched a young aide named Pat Buchanan to make peace with National Review. Buchanan would later go on to run for president and serve as a kind of harbinger of Trump’s “America First” appeals.

Nixon was elected president in 1968 and reelected by a massive landslide in 1972. He governed as a liberal Republican. His administration had an enormous number of liberals—and even Democrats—in it, including Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Leon Panetta, James Schlesinger, John Connally, and John Roy Price, who wrote a memoir of the Nixon administration, The Last Liberal Republican. No less than Noam Chomsky dubbed Nixon, “the last liberal president”—not even the last liberal Republican president.

“Probably more new regulation was imposed on the economy,” observed Herb Stein, the chairman of Nixon’s Council of Economic Advisers, “than in any other presidency since the New Deal.” Nixon was the father of affirmative action. He launched Supplemental Security Income (SSI); oversaw large expansions of Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid; and proposed far more sweeping expansions of the welfare state under his failed Family Assistance Plan. He proposed and created the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). He signed amendments to the 1967 Clean Air Act calling for reductions in car emissions. On his watch, we got the 1972 Noise Control Act, the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act, the 1973 Endangered Species Act, and the 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act. He proposed sweeping intrusions of the government into health care.

His failed Family Assistance Plan sought to dismantle aspects of New Deal welfare programs, but not out of any zeal for limited government. The plan, Nixon hoped, would cement a “new alignment” by entrenching the white working class, southern Democrats, “new liberals,” and other members of the “silent majority,” who had been moving into the Republican column thanks to perceived Democratic excesses and Nixon’s cultural appeals, particularly on “law and order.” The goal was to create a durable governing majority held together by what political scientist Scott Spitzer calls “Nixon’s New Deal.”

Republicans and Democrats, each for their own reasons, collectively decided to forget all of this. Republicans in the age of Reagan were hardly interested in boasting about any of it. And because Democrats hated Nixon so much, the last thing they wanted to do was admit that they were standing on his shoulders.

Indeed, the narcissism of small differences plays an important role here. In the 1990s, a lot of conservatives hated Bill Clinton—not so much because he was a wild-eyed left-winger, but because he was stealing conservative issues for Democratic ends, from hiring more police to supporting welfare reform. A similar dynamic plagued Democrats. Nixon “stole” their Great Society and New Deal ideas and used them to cobble together a massive Republican presidential coalition.

The relevance for today should be obvious, but it isn’t. The GOP is Nixonifying before our eyes. Leave aside Trump’s open plagiarizing of Nixon’s language and playbooks. The “silent majority” was Nixon’s thing. Attacking the liberal media was Nixon’s thing. “Law and order,” “the forgotten man,” and going after “elites” was a Nixon thing—and stemmed from similar resentments. In a taped conversation with Henry Kissinger, Nixon said, “The press is the enemy. The press is the enemy. The establishment is the enemy. The professors are the enemy. … Write that on the blackboard 100 times and never forget it.” In his 1968 acceptance speech at the Republican Convention, Nixon acknowledged “the voice of the great majority of Americans, the forgotten Americans—the non-shouters; the non-demonstrators.” Who does that sound like? It’s no coincidence that Trump has always been close to Roger Stone, who was a Nixon dirty-tricks guy from the beginning.

The GOP’s Nixonification isn’t just about branding and rhetoric. If you’re looking for a precedent for Trump’s foreign policy, Nixon is your guy. If you’re looking for a precedent for his domestic policy, Nixon is your guy. If you’re looking for legal precedents for a lot of his maneuvers, again, Nixon’s your guy.

Now, the reason I think all of this is so relevant and interesting is that some folks on the new right are starting to realize that, well, Nixon is their guy. Chris Rufo has an interesting piece arguing that J.D. Vance needs to be … a new Nixon:

How should Vance approach this challenge? To answer that question, we might recall the experience of another man who rose to the vice presidency early in life, dealt with the problems of racialism and conspiracism within the Right, and, through trial and error, learned how to manage a coalition, win the presidency, and win reelection in a 49-state landslide: Richard Nixon.

I agree with some of Rufo’s points about the problems afflicting the right. And his argument is not necessarily wrong or even implausible as political advice for Vance (I have objections). But what I find so interesting is that an intellectual architect of the new right is lionizing a politician who was so contemptuous of conservative ideology. Nixon was a liberal pragmatist, a “me-too Republican.” He was brilliant in many respects and did some truly impressive things, especially on foreign policy. But what animated him was resentment of his enemies and a concerted desire for political power. Ideas were way down on his list.

I’ve been saying for a very long time that much of the new right really isn’t about ideas, but about seeking power. I find it oddly reassuring that some of the leading lights of the new right are essentially admitting as much as they embrace the me-too Republicanism the conservative movement was created to oppose.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.