Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

You're reading the G-File, Jonah Goldberg's biweekly newsletter on politics and culture. To unlock the full version, become a Dispatch member today.

Hey,

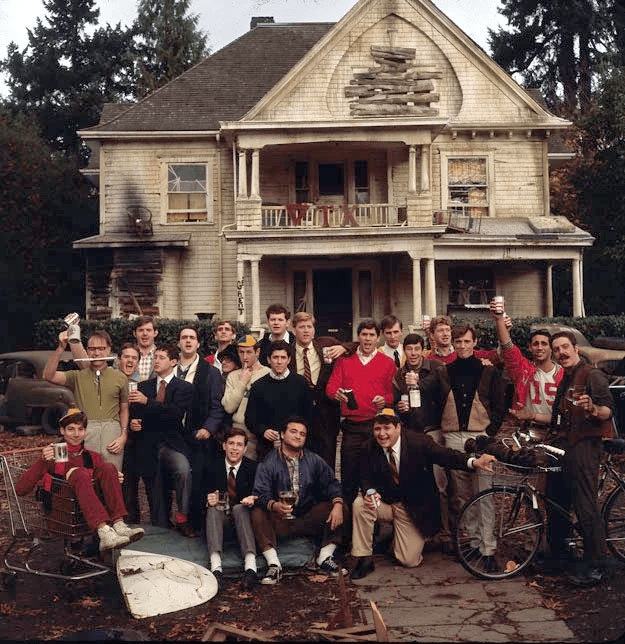

Twenty-four years ago, I wrote a silly G-File addressing the pressing question: “What is the most Burkean line from National Lampoon’s Animal House?”

Rereading it now fills me with feelings—nostalgia most of all. It was a simpler time! Sid Blumenthal and Jesse Jackson jokes! There’s also a smattering of pride. That kind of stuff helped National Review Online—and yours truly—find a distinctive voice. “You got the chocolate of pop culture references in the peanut butter of conservative philosophy!” And, there’s a bit of wince-inducing embarrassment at the jocularity and juvenilia of it all.

But none of that is important right now, save as an introduction to the most pressing question of the moment: “What is the most Madisonian line from Animal House?”

You are receiving the free, truncated version of The G-File. To read Jonah’s full newsletter—and unlock all of our stories, podcasts, and community benefits—join The Dispatch as a paying member.

As Leo Strauss never observed, it should not surprise us that some of the contenders for the most Burkean line would also be in the running for most Madisonian line. Burke and Madison were both nuanced advocates for small-r republican principles, sharing an understanding of the flawed nature of man. As Madison famously said, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary.” Burke was less pithy, but was getting at much the same idea in “A Letter to a Member of the National Assembly”:

Men are qualified for civil liberty, in exact proportion to their disposition to put moral chains upon their own appetites. . . . Society cannot exist unless a controlling power upon will and appetite be placed somewhere, and the less of it there is within, the more there must be without. It is ordained in the eternal constitution of things, that men of intemperate minds cannot be free. Their passions forge their fetters.

In Federalist No. 55, Madison notes that just as “there is a degree of depravity in mankind which requires a certain degree of circumspection and distrust, so there are other qualities in human nature which justify a certain portion of esteem and confidence. Republican government presupposes the existence of these qualities in a higher degree than any other form.”

One can draw a not-entirely-straight line from these observations to Dean Wormer’s deployment of “double-secret probation.” At the same time, as the villain of the tale, Wormer is distinctly un-Madisonian. When he says, “The time has come for someone to put his foot down. And that foot is me,” he typifies the kind of political leadership Madison abhorred. Or as D-Day declares in a moment of despair, “War’s over, man. Wormer dropped the big one.” In our Madisonian system of checks and balances, there is no final foot, no unilateral “big one.” The people always have an avenue to counter tyranny and rectify injustice.

Still, it would not be right to say that Madison would consider the members of the Delta Tau Chi fraternity to be heroes either. Madison would reject Eric “Otter” Stratton’s defense of Delta House’s depravity:

The issue here is not whether we broke a few rules, or took a few liberties with our female party guests — we did. [winks at Dean Wormer] But you can’t hold a whole fraternity responsible for the behavior of a few, sick, twisted individuals. For if you do, then shouldn’t we blame the whole fraternity system? And if the whole fraternity system is guilty, then isn’t this an indictment of our educational institutions in general? I put it to you, Greg — isn’t this an indictment of our entire American society? Well, you can do whatever you want to us, but we’re not going to sit here and listen to you badmouth the United States of America!

The whole point of Madisonian institutionalism is to contain error at the lowest level possible. The sins of Delta House are not the sins of the United States of America. Such demagogic guilt-by-association is decidedly un-republican. As Madison says in Federalist No. 10: “If a faction consists of less than a majority, relief is supplied by the republican principle, which enables the majority to defeat its sinister views by regular vote: It may clog the administration, it may convulse the society; but it will be unable to execute and mask its violence under the forms of the constitution.” The Greek council may have been run by an officious impotent schmuck in the form of Greg Marmalard who was too besotted with the executive. But by expelling Delta Tau Chi it was nonetheless exercising the republican principle. “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition … ” Madison insists. “The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place.”

For this reason, I think a powerful contender for the most Madisonian line comes from Otter when he tells Flounder, “You f—ed up, you trusted us.” For Madison, the fallenness of man is a permanent fixture of the human condition. Put not your faith in princes. Don’t trust people—put your trust in structures, institutions, rules that channel man’s nature in productive ways.

I’d say that wins the contest, save for the fact that the real point of this “news”letter—at long last—is to once again crap on Congress, the institution nearest and dearest to Madison’s heart and the linchpin of our constitutional order.

I know I’ve been doing that a lot lately, but this Wall Street Journal article sent me into a rage that burns brighter and hotter than the kiln explosion that tragically took Fawn Liebowitz’s life. From the Journal:

Inside the White House, top advisers joke that they are ruling Congress with an ‘iron fist,’ according to people who have heard the comments. Steve Bannon, the influential Trump ally, likened Congress to the Duma, the Russian assembly that is largely ceremonial.

I wish Bannon’s contempt for Congress wasn’t so apt. Congress has rendered itself into a studio audience for the Trump show. Trump has made things worse, but the trend predates him by decades.

I’ve said a million times that perhaps the biggest mistake the founding fathers made was assuming that Congress would remain a zealous guardian of its own rights and privileges, i.e. its power. Madison’s belief that ambition would check ambition is the only way this thing can work.

You know the type of person who is a kind of fanatic about the First or Second Amendment? Some people are like that about civil rights. I mean the sort of absolutist who has a knee-jerk defensive response to even rhetorical incursions into the sanctity of their inviolable rights. Yes, they can be annoying sometimes. But those sorts of people play a crucial function in our system. They are an early warning system, canaries in the coal mine. They spot a potential threat on the horizon and leap to the slippery slopes that will follow if the threat is not quashed immediately.

This attitude used to be much more widely held. As Burke said, “In other countries, the people, more simple, and of a less mercurial cast, judge of an ill principle in government only by an actual grievance; [In America] they anticipate the evil, and judge of the pressure of the grievance by the badness of the principle. They augur misgovernment at a distance; and snuff the approach of tyranny in every tainted breeze."

Well, as an institution, Congress used to be like this—not necessarily about free speech, or guns, and certainly not civil rights or the 10th Amendment. But its members were like that about their own power and authority. That might seem grubbier than lofty convictions about inalienable rights. But our system depends on Congress protecting its rights and privileges every bit as much as it depends on the Bill of Rights.

When members of Congress take an oath to uphold the Constitution, that doesn’t just mean they shouldn’t violate it by passing laws that infringe on the Bill of Rights. It means they are honor-bound—by an oath most of them took on a Bible—to play their role. And their role is to uphold the role of the Congress in the constitutional order. That is why they are there, not to raise money for the next election or to land a gig on TV or K Street.

Their role requires them to insist that taxes originate in the House, that the executive seek approval from the Senate for treaties (which Barack Obama refused to do with his nuclear deal with Iran), to guard their exclusive authority to, among other things, declare war, allocate taxpayer dollars, and, more broadly, to produce legislation after extensive debate and deliberation. In other words, the job of Congress is to be Congress, and that means it is supposed to assert its centrality in the constitutional order and the processes that flow from it. Allowing the president to defund agencies and programs Congress lawfully funded is pure cowardice. Allowing the president to wage war without congressional approval is cowardice. Applauding false rhetoric about insurrection, sitting quietly by as Cabinet officials mock senators during constitutionally required oversight hearings, is cowardice. Refusing to object as the president simply appropriates both the power of appropriation and taxation while sometimes hoping—sometimes not—that the courts will defend Congress when Congress is too scared to do so is cowardice.

I don’t want to go all AP American History on your posterior, but that’s what Congress used to do. Here are a few examples for those interested (for those who aren’t you can just skip ahead to find out the most Madisonian line from Animal House).

Those were the days.

When George Washington signed the Jay Treaty, his supporters in the Senate ratified it. But opponents of the treaty in the House, led by James Madison (again, sort of an expert on the Constitution), argued the president and Senate having exclusive authority to sign and ratify treaties didn’t bind the House to fund the damn things. “The House of Representatives ought to be equally careful to avoid encroachments on the authority given to other departments,” Madison explained, “and to guard their own authority against encroachments from the other departments.”

If the president and the Senate could approve a treaty with Britain or anyone else and by doing so require the House to fund its requirements then, Madison explained, the House “would be the mere instrument of the will of another department, and would have no will of its own.”

Andrew Jackson ordered deposits be taken out of the Second Bank of the United States, but only after firing William Duane, the treasury secretary, for refusing to do so because it was unlawful, reckless, and a usurpation of congressional authority. He replaced Duane with the Lindsey Halligan of the day, the more pliable Attorney General Roger Taney, who followed Jackson’s order. Congress censured Jackson for his actions. “Resolved, That the President … has assumed upon himself authority and power not conferred by the Constitution and laws, but in derogation of both.”

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the House routinely insisted that all tariffs “originate” in the House because only the House can raise taxes. (Sound familiar?)

In the “Rules revolt” members argued—rightly—that the power of Congress resides in the members, not in the House speaker’s office.

When Teddy Roosevelt smeared Congress in an address, suggesting that the Secret Service should be able to investigate the legislative branch and that Congress feared such investigation because of its corruption, Congress replied with a decorous F— You. A series of resolutions stated that Congress would henceforth ignore any communication from the president that lacked the required respect and deference. One member declared, to applause, that if Congress didn’t pass the resolutions, “it would not only convict itself of a lack of proper self-respect, but it would indicate a degree of supineness [sic] which would make it contemptible in the eyes of the people of this country, and even in the eyes of the President himself.”

Sen. Burton K. Wheeler, of whom I am not a particular fan, helped expose the Teapot Dome scandal. When the Department of Justice subsequently investigated Wheeler for corruption, he framed it as executive payback (highly debatable) and an encroachment into the Senate’s autonomy (more plausible). Wheeler demanded the Senate itself investigate him. It did and exonerated him. The spirit of “we police our own” won the day.

And that brings me to the most Madisonian line of Animal House.

A Congress of Flounders.

The members of Delta House don’t particularly like one of their freshman pledges, Kent Dorfman, aka Flounder. But he’s a legacy, and they need the dues (and, as Otter had pointed out earlier, it’s not like the other members have much ground to stand on). So, they admit him. Later, when the officious bully Doug Neidermeyer is humiliating Flounder on the ROTC parade grounds, Otter and Boon take great offense. “He can’t do that to our pledges. Only we can do that to our pledges.” They are not claiming Flounder is beneath contempt; they are protecting him from the unjust contempt of another faction, another branch. And so they launch a golf ball at a literal horse’s ass to sanction a figurative horse’s ass.

That is how Madison would have wanted it.

A lot of people, particularly lawyers and those who play them on TV, love to talk about the Constitution as a legal document. I get it; it lays down the skeleton of our legal system. But a purely legalistic interpretation not only ignores the muscle and sinew of the system, it misses the soul too. The most glaring example of this is during presidential impeachments, when an explicitly political trial adopts the legalisms of a criminal court so that the members can dodge their republican obligation to consider issues larger than mere criminality.

As Yuval Levin laid out in brilliant detail in his 2024 book on the subject, the Constitution is a covenant. Covenants are contracts, but they aren’t mere contracts. The Constitution is a covenant because it obliges Americans, and particularly elected and judicial officeholders, to a form not just of government, but governing. In many of the examples I cited, Congress didn’t always have the best arguments or the best facts on its side, but it did have a conviction that Congress—the supreme branch—wasn’t supposed to be bossed around because Congress—not the presidency and certainly not the courts—is the branch of government that most represents the people. And here, the people rule.

When Congress is treated like a prop of, or foil for, the executive branch, when members of Congress consider loyalty to a man or a party more important than loyalty to the institution they are stewards of, when they ignore their obligations under the Constitution to play the role assigned to them by it and dole out their responsibilities to the executive or the courts like a bunch of Tom Sawyers getting out of painting the fence, they are violating the spirit of their oath every bit as much as they would be if they took a bribe or voted to make the president a king.

And when Congress lets the executive humiliate it by taking its rights and privileges from it because politically that’s the most expedient path to mere reelection to the American Duma, they are collectively a profile in cowardice.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.