Alas, politics in Washington, D.C., continues.

The federal government is bracing for a shutdown, driven by Democrats in Congress itching for a fight with President Donald Trump, ostensibly over health care policy (and spending). Trump is itching for a fight with, well, everybody. In the past week, Trump demanded Attorney General Pam Bondi fire the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia—that he himself appointed—because said attorney concluded there was insufficient evidence to indict one of the president's political opponents, New York Attorney General Leticia James, a Democrat, on allegations of mortgage fraud. The federal prosecutor in question, Erik Siebert, ultimately resigned and was replaced by a Trump loyalist, Mary Cleary.

Congressional Republicans, meanwhile, are itching to avoid a fight over the saga of convicted sexual predator Jeffrey Epstein. House GOP leaders are hoping to persuade members of their party to oppose Democratic efforts to bring more evidence to light via parliamentary tactics that allow members to force a floor vote over the objections of the majority party's leadership, specifically, the speaker.

—David

Top Stories From the Dispatch Politics Team

Recent Justice Department scandals show that government lawyers are serving the president, not the Constitution.

Buried in the nearly 1,000 pages of President Donald Trump’s tax-cuts-and-spending bill was a little-noticed tax write-off change that has since drawn criticism from gambling industry interests and a bipartisan group of senators. That this change came to be included in the package of measures extending tax cuts in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act exemplifies the issues that can arise from Congress using the reconciliation process to pass legislation, especially when that legislation is packed full of so many provisions that legislators and their staffs often can’t digest everything before having to cast a vote. But it also is part of a larger conversation about the broader effects of gambling in America and whether the government should disincentivize it.

In the United States, K-12 education is mostly run as a government service. By contrast, higher education is supposed to operate more like a marketplace. In theory, that means competition should drive innovation, keep colleges responsive to students’ needs, and ensure tuition prices reflect the real value of a degree. But in practice, however, the market for higher education is hugely distorted. A few powerful forces—federal subsidies, confusing pricing, and rigid accreditation rules—distort how colleges and universities respond to students. The result is an education sector that costs more than it should, delivers uneven quality, and innovates too little.

Going to war against the Federal Reserve seems baseless when current interest rates—while above the anomalous 2010s levels—are not high by historical standards. Moreover, rates are not holding back the current economy, and they may even be too low to combat the recent inflation uptick. However, President Trump has offered an additional argument: Lower interest rates would reduce Washington’s interest on the national debt, “saving us $1 Trillion per year” in reduced budget deficits. This sacrificing of Federal Reserve independence to help the Treasury sell cheaper debt is known to economists as “fiscal dominance.”

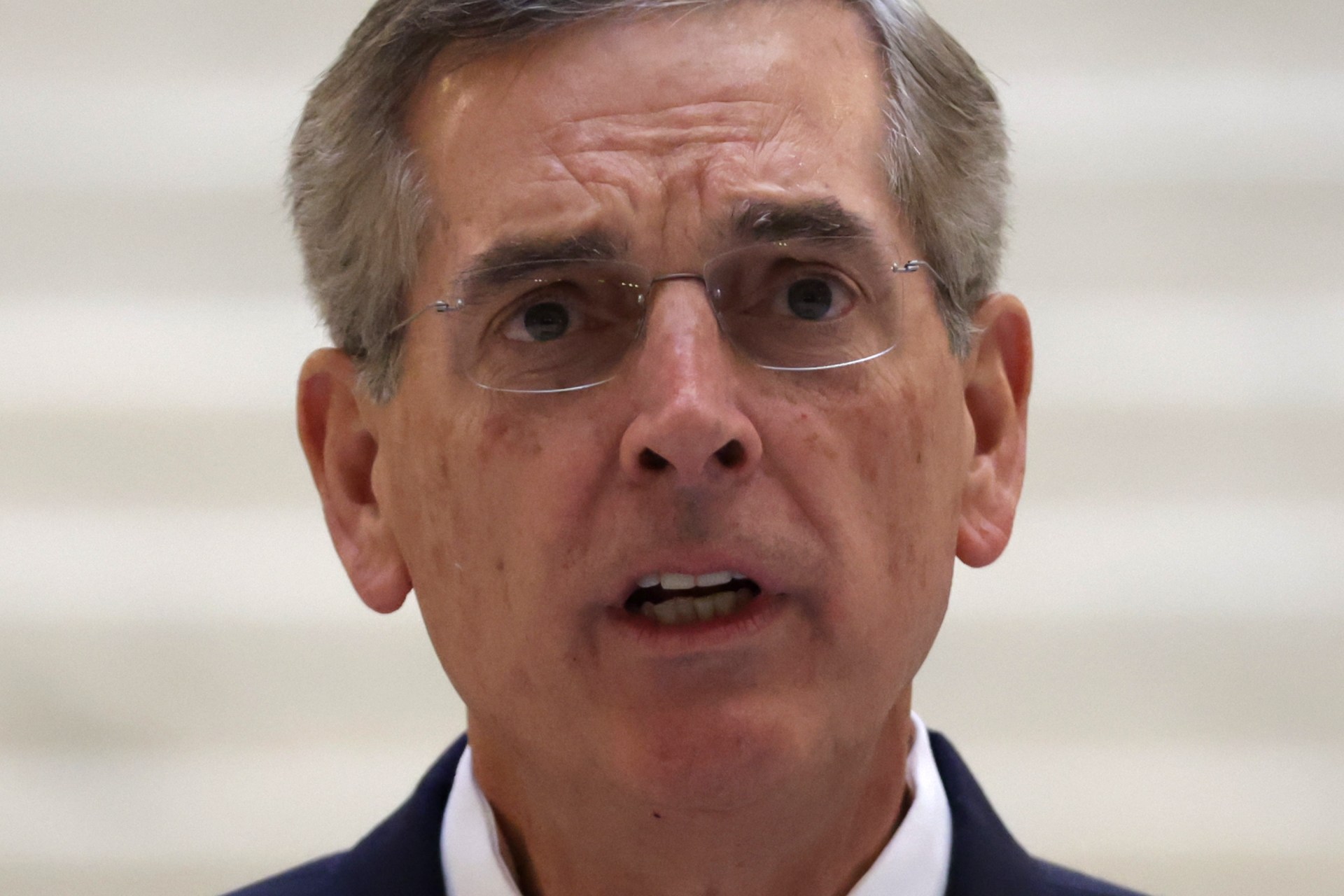

It was some time in early 2021, weeks after the January 6 riot at the Capitol, when a Republican source from Georgia told me what was then practically banal, conventional wisdom: Brad Raffensperger, the Republican secretary of state who had defied Donald Trump’s demand to change Georgia’s election results, had no political future. Raffensperger had, along with Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp, earned the wrath of the losing president and his MAGA base. Peach State Republicans were mad: mad that Trump had lost the state to Joe Biden, mad that both of its Republican senators had lost their runoff elections and handed control of the U.S. Senate to the Democratic Party, mad that Raffensperger and Kemp didn’t do anything to stop what Trump claimed was a stolen election. The question was not whether Raffensperger would announce he was not running for reelection in 2022, but when.

Enjoying our Dispatch Politics Roundup? Consider forwarding this article to someone you know who likes independent, fact-based journalism.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.