Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

We’re actively working on improvements to better serve our community, and we want to hear directly from our readers about their experience with our content. Will you take 5-10 minutes to share your thoughts in a quick survey? Your responses will help us continue to improve your Dispatch experience.

We’re actively working on improvements to better serve our community, and we want to hear directly from our members about their experience with our content. Will you take 5-10 minutes to share your thoughts in a quick survey? Your responses will help us continue to improve your Dispatch experience.

Happy Sunday, and happy New Year to readers who this past week celebrated Rosh Hashanah. This week’s Dispatch Faith features on-the-ground reporting from Joseph Roche, who observed the largest Rosh Hashanah pilgrimage outside of Israel in Ukraine.

Though fewer Jews have traveled to Uman, Ukraine, since Russia’s 2022 invasion, the city hosted more than 35,000 pilgrims this year, local officials said. We’ll have more reporting from Joseph in next week’s newsletter as well.

Joseph Roche: Marking the Jewish New Year in a Time of War

UMAN, Ukraine—In Uman, a city in the Cherkasy region about two hours by bus from Kyiv, the sun dips toward the horizon.

Along Pushkin Street, the heart of the local Jewish community, hundreds of pilgrims raise their voices in a mournful song. Some sway in dance, others strike their chests, their arms stretching upward as if reaching for the heavens.

It marks the fourth time the pilgrimage has taken place since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022.

Every Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, this small city of nearly 90,000 hosts the largest Jewish pilgrimage outside Israel. More than 35,000 pilgrims are present this year, according to Andriy Demchenko, spokesman for the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine.

Despite the war, the celebrations stretch on for days and nights, with prayer, dancing, and singing filling the streets. Organized events, concerts featuring religious music, and communal meals punctuate the more spontaneous gatherings that break out in courtyards and alleys. Attendance has dipped since the invasion, as before 2022 numbers often reached more than 40,000 or even 50,000, but the scale remains striking given the circumstances. For Uman, the presence of so many pilgrims transforms the city into a hub of noise, devotion, and festivity, even as the shadow of war hangs over the country.

Each year, tens of thousands of Jews journey to Uman from Israel, France, the United States, and many other countries to pray at the grave of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov. The 18th-century Hasidic master is remembered for teaching that joy, dance, and song form the very heart of Jewish devotion.

Rabbi Shmuel Levy, who traveled from Paris, says Rabbi Nachman’s message is especially powerful today. “Even though you have war here, and war in Israel, and war all over the world, Rabbi Nachman teaches us to keep joy alive,” he explains. “That is why we dance, why we sing. It is our way to push back against despair.”

Since his death in 1810, his burial site has become a focal point of pilgrimage, not only for Breslov Hasidim but also for Jews of every background seeking a deeper connection to God. Unlike many other Hasidic groups, the Breslov movement did not establish a hereditary dynasty after Rabbi Nachman’s death. Instead, his teachings themselves became the unifying force, with an emphasis on personal joy, heartfelt prayer, and a direct, individual relationship with God. This openness has made Uman a destination not just for Breslovers but for a wide spectrum of Jews who find in Rabbi Nachman’s legacy a path toward spiritual renewal.

“In Uman, you find every kind of Jew,” says Yossef, an Orthodox follower of Rabbi Nachman from Créteil, near Paris. “There are secular Jews, Sephardim from North Africa, Ashkenazim from Eastern Europe, Hasidim, Breslovers, traditionalists, but here we are all united.”

Rabbi Shmuel Levy of Paris recalls that Nachman deliberately chose Uman as his final resting place to remain close to the souls of thousands of Jews slain by Cossacks during an 18th-century massacre.

Born in 1772 in the town of Medzhybizh, the birthplace of Hasidism, Rabbi Nachman was the great-grandson of the Baal Shem Tov, the movement’s founder. From an early age, he sought solitude in forests and fields, where he developed the practice of hitbodedut, a form of secluded, personal prayer spoken in one’s own words. Throughout his short life, he traveled widely, including a fateful journey to the land of Israel in 1798, which deepened his mystical teachings and gave him great stature among Hasidim.

During his final years, weakened by tuberculosis, he settled in Uman and gathered disciples around him. Before his death in 1810, he promised that those who would visit his tomb, give tsedaka (charity), and recite 10 specific Psalms known as the Tikkun HaKlali would be shielded from the torments of hell. For his followers, these words remain a spiritual guarantee, one that continues to draw tens of thousands of pilgrims to Uman more than two centuries later.

“It is for the sake of their blood that our teacher wished to be buried here,” Levy continues. “Uman is the lowest place on earth because of that tragedy, but Rabbi Nachman shows us that through prayer and dance we can transform the lowest point into a place so full of love for God that even angels envy it. That is why, year after year, we return to intercede.”

Security concerns.

In front of a small Soviet-era brick house, a couple of hundred meters from the epicenter of the festival, the dissonant chants of a dozen pilgrims rise from the courtyard. They gather beneath a dusty blue arbor, where a vine winds upward, heavy with clusters of pale green grapes.

Two rabbis lead the prayers. Clad in long white djellabas and kufis, their voices reveal their Moroccan origins.

Having come from Beersheba, Israel, the twin brother rabbis guide their disciples in song before blowing the ram’s horn, the shofar, a symbol of renewal and divine judgment. They have come with students from their yeshiva. One of them, Ador, 30, explains that this is his second time here. “In Uman, God promised to bless those who come and give them strength for the coming year if they visit Rabbi Nachman’s grave,” he says.

Divorced less than three years ago, Ador says his first pilgrimage helped him endure the suffering of his marriage ending, and he hopes for the same again this year.

Security concerns do not weigh heavily on him. “We live in southern Israel, right next to Gaza. We are used to being shot at.”

Yet in Uman, security is never far from mind. The Ukrainian authorities coordinate protection with police patrols, checkpoints, and controlled access to the pilgrimage zone—measures that predate the war and have long been part of handling the influx of tens of thousands of visitors. Alongside them, hundreds of Israeli volunteers work together with the Ukrainian police and emergency services to smooth out the flow of pilgrims and respond quickly to any incident.

Although the city is more than 300 kilometers from the southern front and approximately 500 kilometers from the Donbas, and with no decisive military facilities nearby, such precautions are seen as necessary. Uman has so far been spared direct strikes, but in a country regularly targeted by drones and missiles, visible security offers reassurance to pilgrims and locals alike.

One of Ador’s friends cuts in with irony, asking if the country is really at war. Haim, one of the group leaders, answers firmly. “The country is much bigger than Israel,” he says. “The war is far away. Here we are in the middle of nowhere, but that does not mean there is no war. Didn’t you see? There were soldiers everywhere.”

Pilgrims from France, by contrast, are more prone to worry. Yossef, 26, from Paris, came with his rabbi for the first time. “My mother cried when I left. She kept asking, ‘Why go there? There is a war.’”

Covered in charms and lucky trinkets he bought earlier in Uman, and wearing a white crocheted kippah, the symbol of the Breslov Jews, he lightens the mood with a joke but admits he was anxious at first.

“I will not lie. I was a little scared too,” he says. “But now it feels fine. The atmosphere is wonderful, and you can feel Hashem, the way observant Jews refer to God, and His love. Still, I send my mother a message whenever I can.”

Uman as a symbol of love and peace.

Dancers caught in a circle sing a song in memory of Rabbi Nachman. In front of his tomb, dozens upon dozens of faithful from around the world press together. The atmosphere is both chaotic and fervent.

Outside the tomb, men wait in line with cigarettes in hand, lighting them from a candle or another already burning cigarette. According to Jewish law, during Yom Tov, the festival days such as Passover, Shavuot, or Sukkot, one is permitted to light a flame only from an existing fire, but not to strike a new one. Once their cigarette is lit, some return to dance in the circle while others finish smoking before going back to pray at the Rav’s tomb.

“We dance for peace,” shouts one man, his face hidden behind a frizzy beard. This is the second Jewish New Year since October 7, 2023, and the subject of Gaza, the war, or Israel remains sensitive. “We are neither for Netanyahu nor for Trump, we are only for God,” explains Ador.

Moshe, who recently returned from serving in Gaza with the Israel Defense Forces’ Givati Brigade, confesses something unexpected.

“I love war. Whether in Israel or here, I like to feel the atmosphere of war. I like to see soldiers around,” he said before complimenting the Ukrainian army and saying he thinks it’s “more advanced than ours in many fields, especially in drones.”

Shimon, an Orthodox Jew from Paris, takes the opposite view, lamenting the situation in Gaza. He explains that his one dream is to be able to dance with Arabs. “Only if we can all be here together, Jews, Arabs, and Christians, dancing for Hashem’s love. But one day it will happen. When the Messiah comes, we will all dance together.”

More Sunday Reads

- Can you define “religion,” at least as far as legal protections are concerned? For SCOTUSblog earlier this month, Richard Garnett examined a case from the Supreme Court’s previous term that required the justices to take up that task, at least partially. “It seems likely that, to paraphrase Justice Potter Stewart’s 1964 observation about pornography, when it came to ‘religion,’ they ‘knew it when they saw it,’” Garnett wrote. “An ancient derivation is from the Latin word religare, ‘to bind fast.’ St. Augustine endorsed this etymology, and perhaps early Americans did, too. Probably, they would have reflexively and comfortably agreed with James Madison’s characterization, in his now-famous 1785 work ‘Memorial and Remonstrance,’ of ‘religion’ as ‘the duty which we owe to our Creator and the manner of discharging it.’ Protestant Christianity was, no doubt, front of mind for most, but they were aware of other religions and definitely didn’t imagine that the Constitution’s religion-related rules encompassed Christianity only. More than two centuries later, we lack a constitutionalized definition.” Garnett continued: “Some may argue that this specialness is fading. And it is true that the ‘rise of the nones’ is a now familiar, even if not completely understood, phenomenon. But the fact, at least for now, that more people than previously are reporting no religious affiliation or belief does not undermine the importance—indeed, the urgency—of continued, resolute devotion to the legal protection of religious freedom and of the appropriate independence of religious communities and institutions. This project was, and remains, essential to what John Witte calls ‘the American experiment’ and it still adds, as Madison predicted it would, ‘lustre to our country.’ That the task of defining ‘religion’ is tricky—especially given our twin commitments to religious neutrality and respect for pluralism—cannot be an excuse for giving up on respecting and protecting whatever it is.”

- In the Washington Post, Kim Bellware, Michelle Boorstein, and Rachel Hatzipanagos report on how some black pastors in the U.S. are addressing the assassination of Charlie Kirk, who shared their faith but often made provocative comments on race. “In interviews over the past week, Black pastors said they were offended by Kirk’s takes on diversity, including describing the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 as ‘a huge mistake,’” the reporters wrote. “On an episode of his podcast, Kirk criticized United Airlines’ 2021 announcement that 50 percent of graduates from its flight training academy would be women or people of color, saying, ‘If I see a Black pilot, I’m going to be like, boy, I hope he’s qualified.’ Later, Kirk said that his remarks were meant to illustrate that ‘DEI invites unwholesome thinking’ and that he thought ‘anybody of any skin color can become a qualified pilot.’ … Esau McCaulley, an associate professor of the New Testament at Wheaton College in Illinois, said he is trying to strike a delicate balance when addressing Kirk’s death before the multiracial congregation at the church where he is founding pastor. The activist’s words were likely to have been hurtful to many members, McCaulley said, but his death robbed Kirk of a chance to grow in his understanding that empathy is ‘a Christian superpower.’ ‘I believe that no matter who you are or what you’ve done, you have the potential to grow and change to be better. And for that reason, anyone’s death is a tragedy,’ McCaulley said. ‘It’s sad if someone dies in the middle of their story and we never get to see how the rest of it changes, because you never know what God could do in someone’s life.’”

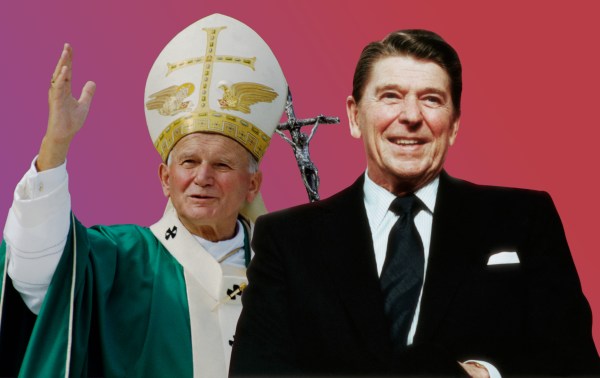

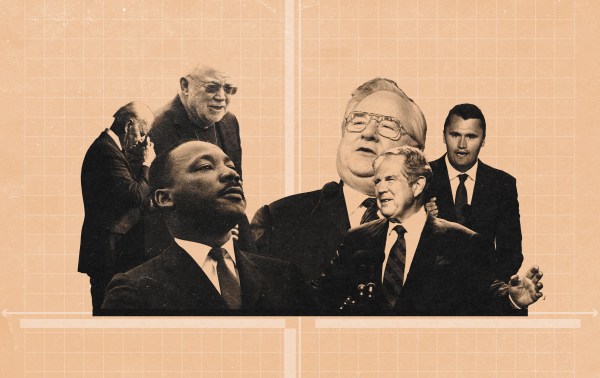

Religion in an Image

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.