Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

We’re actively working on improvements to better serve our community, and we want to hear directly from our readers about their experience with our content. Will you take 5-10 minutes to share your thoughts in a quick survey? Your responses will help us continue to improve your Dispatch experience.

We’re actively working on improvements to better serve our community, and we want to hear directly from our members about their experience with our content. Will you take 5-10 minutes to share your thoughts in a quick survey? Your responses will help us continue to improve your Dispatch experience.

Hi and happy Sunday.

This weekend the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is meeting for its biannual General Conference, a time for members to hear teachings from church leaders. It’s the rare occurrence when the church is meeting without a president, after Russell M. Nelson’s death late last month at age 101.

The church is facing a bit of a crucible, following Nelson’s death, a deadly church attack in Michigan, and the assassination of Charlie Kirk last month in Utah, which touched on so many dynamics related to the church.

It’s in this context that writer Bryan Gentry, a member himself, argues the rest of the country can learn a lesson from a particular story in the Book of Mormon.

A message from The Dispatch

Stay Ahead of the Curve With Dispatch Energy

The Dispatch’s newest weekly newsletter will dive into the politics, policy, and innovation shaping America’s energy future, presented by Pacific Legal Foundation. Featuring a rotating roster of contributors who are experts in their respective fields, each edition will feature incisive analysis on everything from oil and gas and permitting regulations, to renewables, climate, and the grid.

Bryan Gentry: How to Stop Teaching Our Children to Hate

The killing of Charlie Kirk shoved my church into the national spotlight without warning. Many of the people surrounding the Utah incident―from students gathered to hear him speak to the young man accused of shooting him to the governor who took front stage in the manhunt―are or have been members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

It’s not the type of spotlight anyone would audition for, but the show went on: 18 days later, a man with a decade-long anti-Mormon grudge attacked one of the church’s congregations in Grand Blanc, Michigan, killing four people and torching the building. This happened mere hours after Latter-day Saints had learned that our president and prophet Russell M. Nelson had died.

One of the strangest comments I’ve heard during this season was Steve Bannon’s tangent about Utah being “the bluest of the red states,” seeming to lay Kirk’s death partly at the feet of an insufficiently MAGA church. He said, “The shooter’s Mormon, comes from a Mormon family. What is going on out there and why is the Mormon Church not stepping up here in a bigger way?”

Bannon said this at a time Republicans continuously blamed liberal hatred for Kirk’s death. “Violence and murder are the tragic consequences of demonizing those with whom you disagree,” President Donald Trump said. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene wrote on X, “They hate us. They assassinated our nice guy. … Then millions on the left celebrated and made clear they want all of us dead.” Of course, we have seen similar rhetoric among people on the left who accuse Republicans of racist, homophobic or class-based hate. Sometimes it feels like polarized Americans are locked in a contest to prove that the other side hates them more.

Ironically, some of the Book of Mormon stories that Kirk murder suspect Tyler Robinson likely heard growing up could teach Americans of all faiths something about what happens when our politics focuses on the other side’s hate. While we don’t know how much stock Robinson ever put in these stories, the lessons could help illuminate and heal the fault lines that Kirk’s killing expanded.

Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints consider the Book of Mormon an ancient American testament of Jesus Christ, a companion witness to the Old and New testaments. The story begins with a family of Israelites who sail to somewhere in the American continent. The family and their friends split up into two groups, each following one of two brothers, Laman and Nephi, who have a feud similar to Jacob and Esau or Democrats and Republicans. They form two separate nations named Lamanites and Nephites and often go to war.

At the beginning of one skirmish, the story explains that the Lamanites had nurtured a grudge for generations, telling themselves that the founder of the Nephites had repeatedly snubbed his older brother, usurped his authority, and stolen property. According to the story, “Thus they have taught their children that they should hate [the Nephites] … murder them, and …. rob and plunder them, and do all they could to destroy them.”

Kirk’s murder came one day after the Foundation for Independent Rights and Expression’s annual survey showed that one-third of college students believe that violence is acceptable to stop a campus speech, at least in rare circumstances. Some conservatives assumed that attending college radicalized Robinson, and concluded that colleges are teaching their children to hate, so to speak.

The FIRE data doesn’t necessarily indicate that the College Democrats want to shoot you, though. The survey also shows that conservative students support violence more than they used to. A separate survey by political scientist Kevin Wallsten showed that generational factors are at play. Only about 60 percent of Generation Z believes violence is never acceptable to stop a speech, compared to more than 90 percent of boomers who reject violence.

Who taught these children to hate?

Back in the Book of Mormon story, a deeper reading warns us about zooming in on someone else’s hatred. It turns out that the key statement, “they have taught their children that they should hate,” is not part of the scripture’s narration. Nor was it said by a prophet or spiritual leader. It is what a Nephite military leader told his soldiers as they prepared for war. It was his way of inspiring soldiers to kill Lamanites in battle.

A few generations after this particular war, the Book of Mormon tells about a group of Nephites who converted to a belief in Jesus as the coming messiah. They decided to preach repentance to the Lamanites, perhaps like Kirk going onto a college campus to share his views. But many in their society mocked the plan, saying that the better way of dealing with the bloodthirsty, stiffnecked Lamanites would be to go to war and destroy them.

In other words, after generations of telling themselves that the Lamanites were teaching their children to hate, hunt, and destroy the Nephites, the Nephites were prepared to hate, hunt, and destroy the Lamanites. To commit genocide. It turns out that telling your children that someone else hates them is an effective way to teach your children to hate.

Perhaps that explains why both liberal and conservative students are more willing to condone violence—maybe even celebrate it on social media. A high school senior today has no memory of an America that was not extremely polarized. Social media algorithms have fed Americans hyper-negative views for these children’s entire lives. After years of political and cultural leaders doubling down on political division and casting opponents as hateful enemies, young people have learned how to hate very well. One survey found that sizable minorities in each political party thought the world would be better off if many members of the opposing party suddenly died. In the aftermath of Kirk’s shooting, MAGA influencers have said “we’re at war” and called for retribution, and mentions of “Civil War” spiked on social media. The cycle of hate is real.

Those Nephite missionaries in the Book of Mormon could inspire an alternate path for America today, not only for their willingness to engage thoughtfully rather than lead an attack but also for the effect they had on others. The group walked into Lamanite territory and split up. One of them volunteered to serve the ruler of a minor Lamanite kingdom. The king eventually listened to his message and had what you could call a born-again experience, leading thousands of other Lamanites to be converted.

When the new converts discovered that a hostile group was preparing an attack, they buried their weapons as a commitment that they would never kill again. To them, this was “a testimony to God, and also to men, that … rather than shed the blood of their brethren they would give up their own lives; and rather than take away from a brother they would give unto him.” Instead of fighting, they prayed. The attackers cut down some of them until the brutality and depravity of the act sickened them. Some of the attackers swore peace, too.

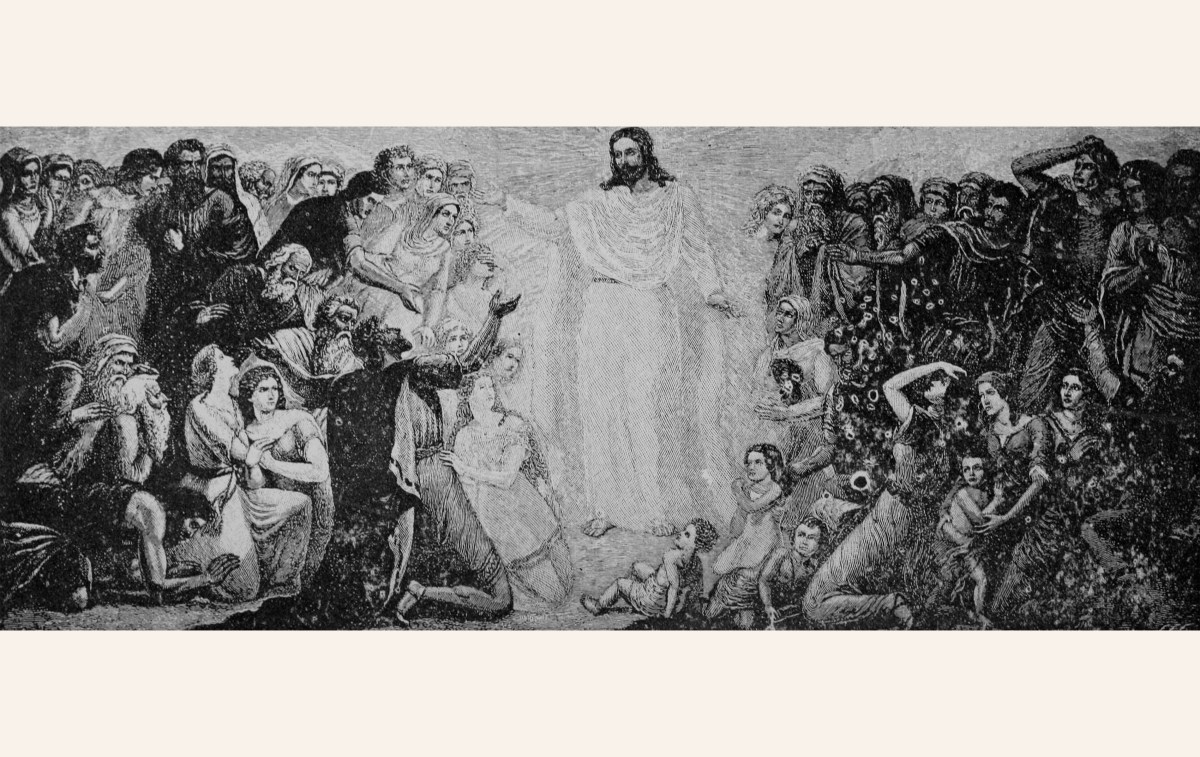

There is a lot more to the story. Eventually, these converted Lamanites flee to the Nephites for protection. Decades later, the Book of Mormon says, Jesus appears to these nations and teaches his gospel, including a version of the Sermon on the Mount: love your enemies, turn the other cheek. His teaching ushers in two centuries of peace. The scripture states, “There was no contention in the land, because of the love of God which did dwell in the hearts of the people.”

One could argue that one central theme of the Book of Mormon is that fostering hatred becomes cyclical, until even someone who otherwise follows the Prince of Peace is willing to take up the sword to stop someone else’s hate. The evidence presented against Tyler Robinson suggests a similar dynamic; prosecutors say he texted his roommate, “Some hate can’t be negotiated out.”

The scripture teaches that the only thing that stops the cycle is someone being the first to lay down their weapons. In today’s divided America, that means checking our own heated rhetoric rather than condemning only the other side’s hatred. Nelson, the church’s leader who died September 27, implored disciples to follow the example of those Lamanites. “Now is the time to bury your weapons of war,” he said in a 2023 talk during the church’s global conference. “If your verbal arsenal is filled with insults and accusations, now is the time to put them away.” He echoed these themes in a Time article marking his 101st birthday a month ago.

I’m not arguing that more peaceful politics depends on massive numbers of Americans accepting the Book of Mormon as scripture. Neither am I suggesting that anyone on either side of politics should accept political violence against them, nor that we must reject moral clarity by ignoring evil acts. The Old Testament Isaiah wrote, and the Book of Mormon quotes him, “Wo unto them that call evil good, and good evil.”

But the core lessons of this narrative matter to America today. Like the two nations in the Book of Mormon, American liberals and conservatives share a common heritage that you can trace to America’s founding, but we have split off into warring factions. Peace does depend on the willingness to set aside poisonous rhetoric that dehumanizes those who disagree. It requires that we be willing to turn the other cheek, to love our enemies, to bless those who curse us.

We must resist the temptation to paint all our political opponents to be just as evil as prosecutors will paint Robinson, as though our opponents, too, are on trial—otherwise, we might teach even more children to hate.

Joseph Roche: The Struggle and Survival of Jewish Life in Ukraine

Last week, we featured Joseph Roche’s on-the-ground reporting on how Jewish pilgrims in Ukraine were celebrating Rosh Hashanah. This week on the site we’re publishing a second installment, in which a handful of native Ukrainians ask: “Are we Jews first or Ukrainian?”

Between neoclassical buildings shaded by overgrown trees, the traveler may glimpse the glorious memory of what Jewish writer Isaac Babel once called “the star of exile.” “From its founding in the 18th century, Jews from all over the Russian Empire, particularly from Brody in Galicia, settled in Odesa and contributed to the city’s development,” explains Isabelle Nemirovski, a scholar of Jewish and Hebrew studies at INALCO in Paris and author of History, Memory, and Representation of Odesa’s Jews: An Old Intimate Dream. “Before the [Holocaust], a third of Odesa’s population was Jewish—about 200,000 people.”

Two hundred years later, after World War II, the Holocaust, Stalinist terror, and the fall of the Soviet Union, what remains of Odesa’s Jewish community struggles to survive. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, which included Odesa as one of Russia’s targets, seemed once again to mark the end of Jewish life in the port city. In the war’s first weeks, the community organized the evacuation of thousands of its members to Israel and Germany. “We went from 35 percent Jewish in Odesa before the [Holocaust] to less than 3 percent today,” Chatrin says with a sigh.

Rabbi Wolf, whose life has been dedicated to strengthening Jewish life in the city, reluctantly agrees with his right-hand man’s analysis. “It’s true,” he admits, “no one will return.” Yet paradoxically, the community is now more determined than ever to maintain its traditions and identity. “The specter of war has created a kind of shock and a survival instinct for what remains of Odesa’s small Jewish community,” Nemirovski explains.

More Sunday Reads

- In a piece for our site on Saturday, Beatrice Scudeler contemplates the virtue of mercy and what many in our current age misunderstand about its nature. “The question is not whether we should respond to someone’s distress—we obviously should—but rather what we consider acceptable means of doing so. Within the Christian tradition, virtues such as charity, justice, and mercy cannot exist separately from each other, but must all be balanced against one another. Yet secular society, though it has not rejected the Christian tradition of the virtues wholesale, has begun to pick and choose which virtues remain ‘virtuous.’ So, we find ourselves in a cultural moment when we highly value the eradication of pain—no matter the cost. As theologian Oliver O’Donovan put it in The Desire of the Nations (1996), ‘compassion for suffering has become an all-important virtue … [it] is the determination to oppose suffering; it functions at arm’s length, basing itself on the rejection of suffering rather than the acceptance of it.’ The risk is that we then place undue weight on the belief that immediate action must be taken to eliminate pain, even if it comes at the expense of destroying a human being in the process. Other virtues—such as the humility to know that we should not make life-and-death decisions, or the patience required to suffer alongside those who are in pain—are forgotten.”

- On Friday, the Church of England voted to name Sarah Mullally as the first woman to be its head as the archbishop of Canterbury. Her being a woman and some of her positions on social issues will be controversial (see this BBC piece for a helpful look at how theologically conservative Anglicans in Africa and Asia see this decision). But in the New York Times, Mark Landler provides important background information on Mullally’s past political stances. “In addition to her role in the church, Archbishop-designate Mullally has a seat in Britain’s House of Lords, which she first secured as bishop of London. If she follows the example set by Archbishop Welby, she could emerge as an important voice on issues like immigration and assisted dying. She has already spoken out against new legislation that would allow terminally ill people to request assistance in ending their lives, a position that she has said is informed by her training as a nurse. Archbishop Welby navigated a bitter, yearslong debate in the church over how to treat same-sex marriage. The Church of England allows priests to bless same-sex couples, though it continues to debate a more formal recognition of these unions. Archbishop-designate Mullally subscribes to the church’s position that marriage is between a man and a woman, though she favors blessings and has urged a more inclusive tone.”

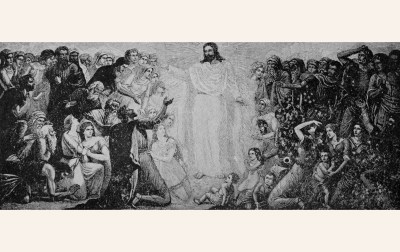

Religion in an Image

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.