Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

Here at The Dispatch, we’re dedicated to cultivating the next generation of thinkers and leaders—that’s why we’re proud to provide low-cost, high-quality Dispatch memberships to students looking to stay informed, think critically, and better engage with the world around them

With your help, we can offer these students free Dispatch memberships and ensure they’re engaging with content that promotes the core values that make our country great—individual liberty, pluralism, patriotism, and capitalism.

Your support can help provide a new wave of young conservatives with better journalism, more thoughtful dialogue, and—hopefully—a brighter outlook on our future.

I’m the first to admit that Capitolism talks about trade too much, but, in my defense, the president keeps forcing my hand. Our latest motivation comes in the form of 25 percent tariffs on sofas and kitchen cabinets, which officially take effect next week and ratchet even higher next year (to 30 and 50 percent, respectively). Admittedly, at this depressing point in 2025, another 25 percent tariff on another consumer product isn’t exactly major news, but what makes these tariffs extra special is how they were imposed and what they say about U.S. tariff and trade policy today.

All of it, as you might imagine, is very bad.

Furniture Tariffs for ‘National Security’?

Maybe the tariffs’ most absurd aspect is that they’re being imposed on wood products for supposed “national security” reasons, pursuant to Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. That law, you may recall, is also the foundation for Trump’s tariffs on steel, aluminum, automotive goods, and copper, as well as pending cases on semiconductors, drones, minerals, heavy-duty trucks, and a range of other products that have at least a plausible connection to the production of U.S. defense goods and military preparedness more broadly. Those cases have major practical and economic flaws, but one could say they pass a “smell test” for some sort of security-related nexus.

As I explained when the wood tariffs case was first announced, however, there’s no plausible case for wood imports to be a national security risk:

If war broke out tomorrow, there’d be zero concern about American “dependence” on foreign lumber or furniture, and domestic sources would be quickly and easily acquired. (We have lots of trees, and these industries neither involve advanced technology nor are highly capital intensive.) Furthermore, nearly half of total US lumber imports come from Canada, a longstanding military ally and close trading partner.

The new Federal Register notice announcing the tariffs reinforces this conclusion. It simply asserts that wood imports are a threat because they’re used by the “Department of War” and in “critical infrastructure sectors” that, if destroyed, “would have a debilitating effect on the national security, economic welfare, or national public health or safety of the United States.” Yet, even leaving aside my initial point (and that freer access to low-cost wood from Canada and elsewhere would actually boost U.S. rebuilding efforts), the FR notice’s very next paragraph acknowledges that “the United States possesses ample raw materials and industrial capacity to meet domestic wood products demand.” In other words, even granting the absurd premise that wood imports might be a security threat, American companies are currently providing the wood the nation (supposedly) needs.

The threat, apparently, is—in the government’s view—threefold: 1) the U.S. wood industry is “underdeveloped” (whatever that means), 2) wood imports are rising, and 3) “Foreign subsidies and unfair trade practices are eroding the competitiveness of the United States wood products industry and disincentivizing investment and modernization.” But the government’s assertions raise another substantive problem: These exact trade issues are addressed by other U.S. laws (namely, the “trade remedies” laws for dumped or subsidized imports or “Section 301” for other unfair trade practices)—laws that have been repeatedly invoked to apply duties on Canadian lumber, Chinese cabinets, and other wood products. Thus, again, even granting the Trump administration’s baseless assertions about the trade threat here, there’s no case for using “national security” tariffs to fix it. They’re just an easy way to get around pesky limitations on the president’s tariff powers—limitations like, you know, the facts and the law.

The baselessness of the government’s assertions—ones used to impose blanket taxes on wood and stuff made with it—reveals the next set of problems, which rest with the law itself. First, Section 232 doesn’t explicitly define “national security,” so it can basically mean whatever the president wants it to mean. Second, the law mandates a report summarizing the government’s findings and conclusions about the alleged security threat at issue (and input from the defense secretary on the same) but doesn’t require publication of these important documents. So, the public—including all the businesses now on the hook for millions in new taxes—has no actual evidence of any real security threat. We just have to take Trump’s word for it (even though he promised these tariffs before the investigation was even begun).

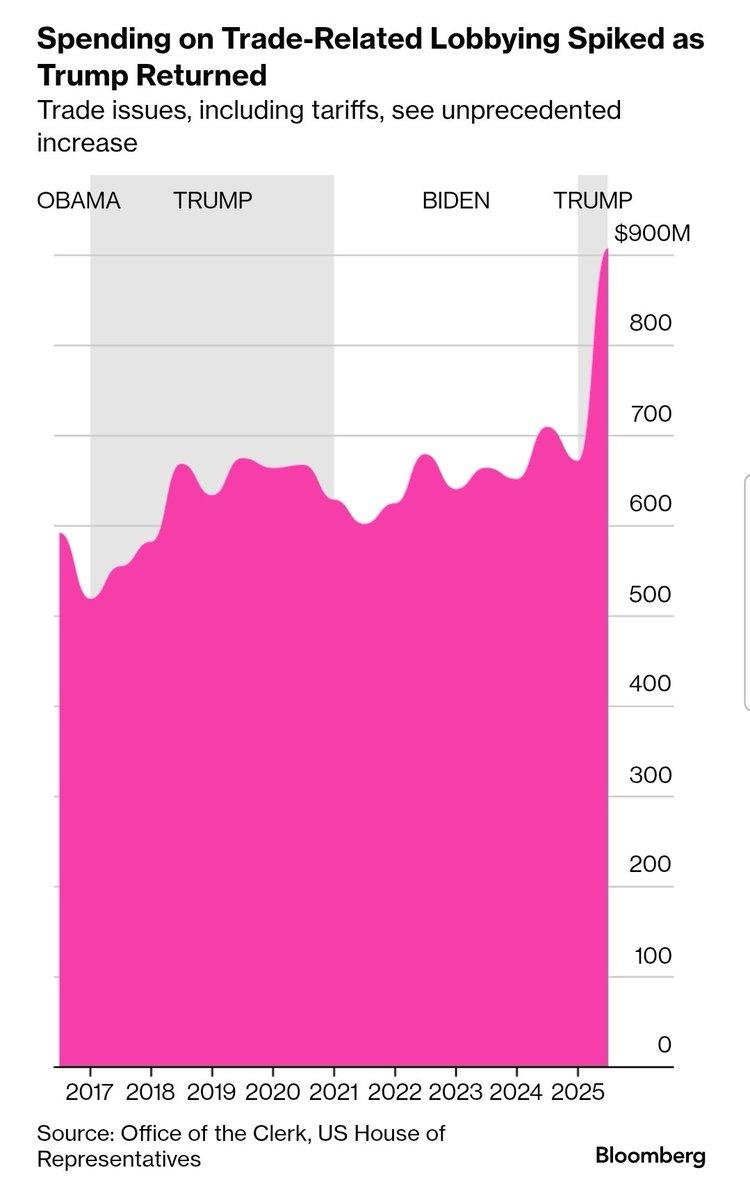

Third, the law’s open-ended mention of “derivatives” lets the administration expand the wood tariffs to cover cabinets, sofas, and other things made from the “threatening” imports at issue—and not just when the tariffs are first imposed. In fact, the Trump administration just used this “tariff inclusion” process to effectively double the scope of steel and aluminum tariffs that Trump first applied way back in 2018. And they plan similar expansions for all the other goods subject to (or soon subject to) Section 232 tariffs—a recipe for endless uncertainty and, of course, lots of cronyism (see Charts of the Week below).

To top it all off, federal courts have (thus far!) been highly deferential to the executive branch in legal challenges involving Section 232, including on things like derivatives. When you put it all together, you get “national security” tariffs on “subsidized” wood, kitchen cabinets, and furniture based on a secret report that not even Congress has seen and despite the existence of other U.S. laws specifically designed to address the problems supposedly identified. It’s insane.

As I said back in March, the wood products case “reveals just how broken both Section 232 and the underlying ‘economic security is national security’ approach to US trade relations are today.” Since then, that conclusion has only gotten stronger.

The Moronic Economics

The wood tariffs’ economics are arguably just as bad. First, there’s the obvious hit to U.S. consumers and the broader housing market, which I explained back in March:

[N]ew tariffs or other import restrictions on lumber and other wood products would mean higher prices for those things in the US market—a particularly heavy burden for already-struggling American homebuilders and homebuyers. Contrary to President Trump’s frequent assertions, Americans paid the tariffs he imposed in his first term, and research we commissioned in 2022 found that US “trade remedy” tariffs (i.e., anti-dumping and countervailing duties) on lumber and other construction materials lead to a persistent increase in their domestic prices—costs builders often passed on to homebuyers.

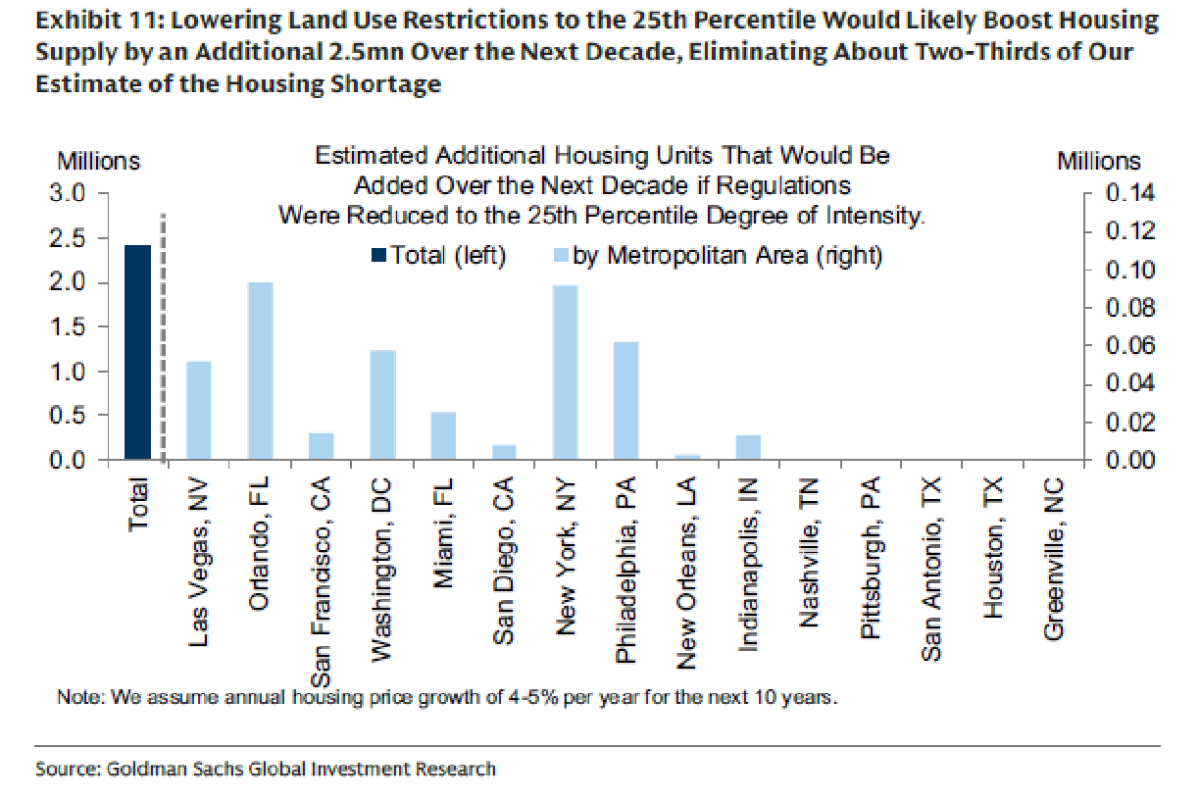

Research from UBS indicates that the new Section 232 tariffs on wood products will add another $1,000 to the cost of building a home, on top of the $8,000 in tariff costs we’ve already seen this year. That might not sound like a lot, but—as we discussed last year—it can have an effect on the margins, discouraging the construction of lower-end starter homes (where costs matter more) or pushing buyers out of certain local markets entirely—especially when coupled with land use, labor, permitting, and other policies that further boost U.S. construction and housing costs. As the New York Times notes, the hit will be particularly bad for lower-income consumers “who buy premade cabinets, vanities or mass-market furniture from the Home Depot and other big-box stores” and in California, where “so many homeowners are rebuilding after devastating wildfires.” And, as usual, the tariffs directly contradict another Trump administration priority: boosting homeownership and housing affordability.

I guess the White House will stow that “national housing emergency” they’d been considering.

The tariffs’ ability to resuscitate the domestic furniture industry and boost U.S. manufacturing jobs is also suspect. As Capitolism has discussed repeatedly, the U.S. furniture industry has evolved over more than a century, with the bulk of labor-intensive production moving first from northern states to the South and then out of the country. That’s left a U.S. industry focused mainly on services like design, marketing, and sales, but with continued production in certain niche areas like custom upholstery that don’t face much direct import competition but do feel the pain of tariffed inputs like wood and metal and of any broader slowdown in the housing market that’s caused by tariffs on construction materials. (These furniture companies also sometimes lobby for targeted tariffs against their U.S. competitors who import from other sources, but that’s a fun story for another time.) The biggest impediment to expanding U.S. furniture manufacturing, meanwhile, isn’t import competition but labor—something tariffs can’t fix (and immigration restrictions hurt). And even communities hardest hit by import competition have long since moved on from an economy dependent on furniture production (see, for example the officially delightful Hickory, North Carolina, where unemployment remains below 4 percent).

Given these well-known facts, it’s no surprise that a big coalition of U.S. furniture companies—both importers and manufacturers—submitted comments to the Trump administration opposing new tariffs on wood products. Along with noting that the original executive order contained multiple errors (LOL), the group argued that neither wood nor furniture products “are in the least bit related to the national security of these great United States,” and that tariffs would actually “harm manufacturing still being done” here by raising production costs and U.S. home prices. They even explained that tariffs would exacerbate manufacturers’ already “severe” difficulties in attracting workers (i.e., “the single biggest challenge for the furniture factories that remain open in the United States”). Their conclusion: “Tariffs cannot reopen factories that no longer exist, bring back thousands of workers who retired or moved on to other industries, nor reverse the interests and inclinations of today’s younger workers, who are attracted to higher-paying trades and the burgeoning tech industry.”

Other informed observers agree with the U.S. producers’ conclusions, and foreign furniture producers apparently do, too. Reuters reported this week, for example, that Vietnamese furnituremakers had no plans to move production to the United States due to our labor challenges and high production costs (which, of course, the tariffs exacerbate). Instead, they’ll just raise prices in the United States and look to sell into other markets. Hooray?

What Are We Even Doing?

More broadly, the wood tariffs show a major flaw in Trump’s bazooka-style use of trade policy to “reindustrialize” the United States: broad and indiscriminate tariffs, especially on inputs, could end up giving us precisely the type of low-skill manufacturing we don’t want—and do so at the expense of the advanced manufacturing we do.

Recent research shows why.

First, a new paper from economist Joseph Steinberg shows the short- and long-term effects of various tariffs on U.S. manufacturing jobs. He finds that blanket tariffs can modestly boost industrial employment overall (under certain ideal conditions and in the long run after a painful adjustment period), but they do it primarily by shrinking many advanced manufacturing industries (e.g., automotive, pharmaceuticals, chemicals—which Steinberg calls “steel” and “cars” as shorthand) and by expanding more basic and lower-skill ones (e.g., paper, textiles, consumer electronics—called “oil” and “toys”). Wood products unsurprisingly fall into this latter category, and the chart below shows the effects for blanket tariffs (“all”) like the ones we’re getting:

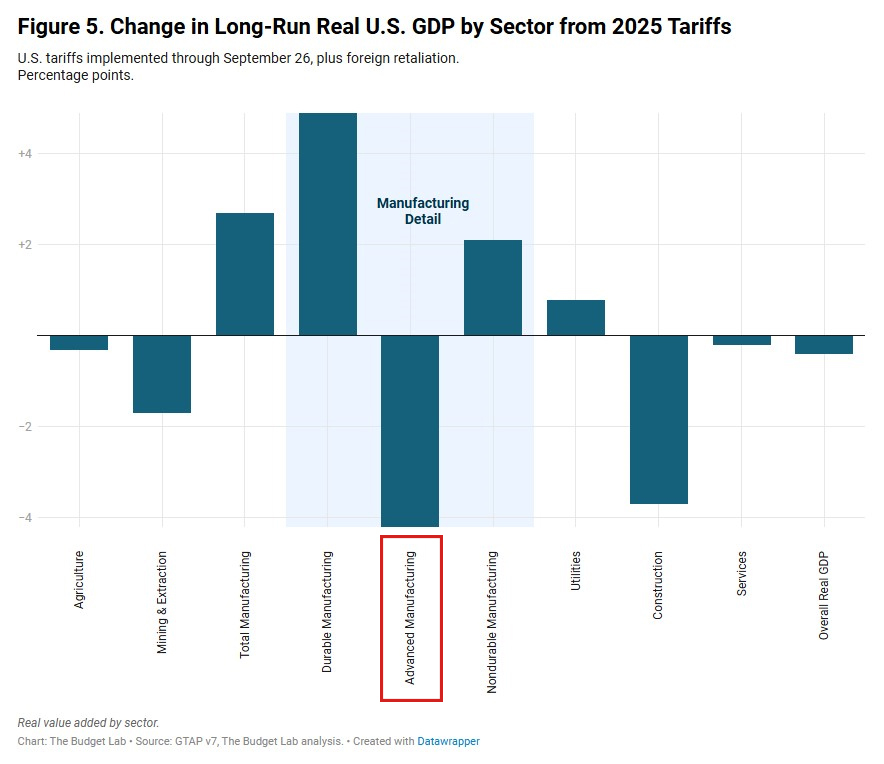

Research from the Yale Budget Lab shows similar effects based on current U.S. tariff levels: Total U.S. manufacturing output indeed goes up (eventually), but advanced manufacturing goes down:

As Steinberg put it on Twitter, “Tariffs can ‘reindustrialize’ the U.S.” eventually, but this growth is painful and “masks reallocation away from advanced manufacturing to downstream consumer goods” like furniture (his "toys"). That result makes perfect sense in a dynamic U.S. economy facing real constraints on industrial resources like labor, materials, machinery, and capital, but, Steinberg adds, it’s a far cry from what modern protectionists are promising us.

This result also makes perfect sense given the modern U.S. manufacturing sector’s global integration—a longstanding trend (and Capitolism topic) that new research again demonstrates. In particular, the Economic Innovation Group’s Jason He and Connor O’Brien examined Bureau of Economic Analysis data on U.S. manufacturers’ purchases of intermediate inputs (i.e., what firms use to produce final goods) and investment in capital equipment (i.e., the tools and machinery the firms deploy) to measure various industries’ reliance on imports. As shown in the chart below, the authors find that “advanced manufacturing is particularly reliant on production inputs and equipment from abroad,” and that high-tech U.S. manufacturers mostly source their products from allies, not China. Thus, they conclude, blunt tariffs will harm the high-tech industries we should want in the U.S. economy—and national security along the way.

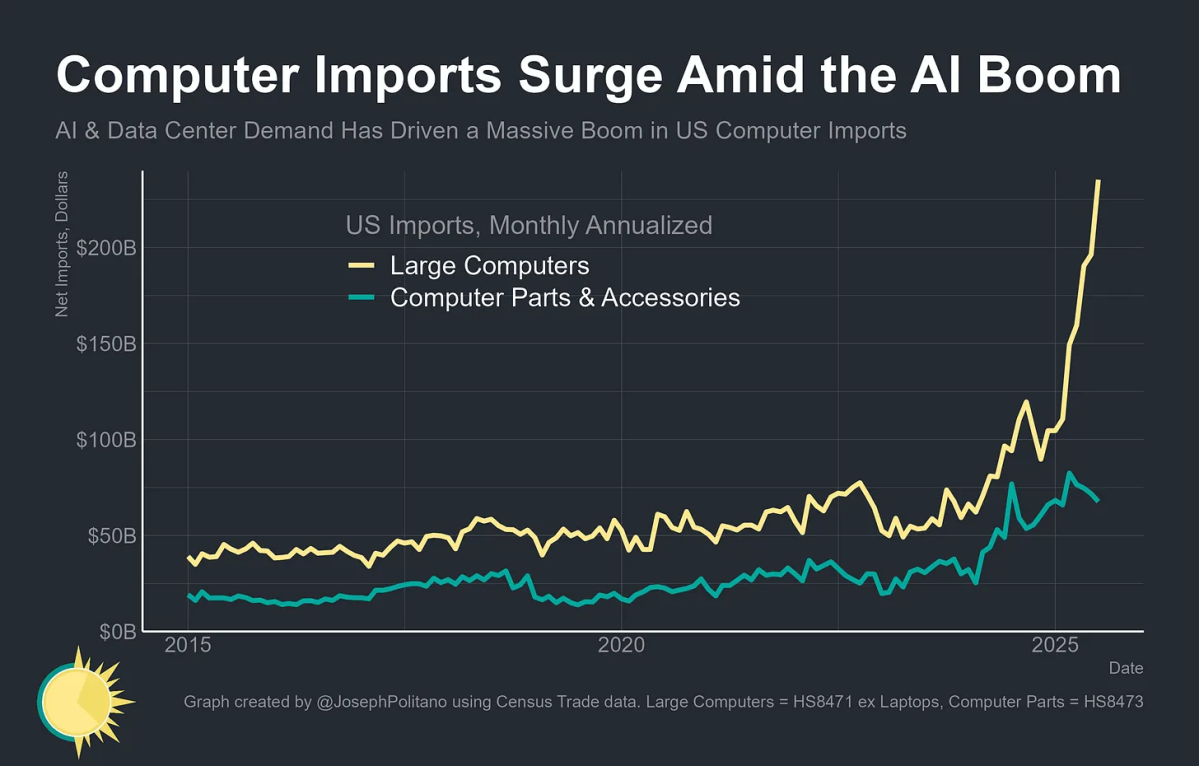

Whether intentionally or not, the Trump administration seems to understand this reality at some level and for some products. As O’Brien and He note, for example, recent trade deals with Japan and the European Union apply lower tariffs on pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, and aerospace parts “[l]ikely in recognition of advanced manufacturing’s dependence on global supply chains” (and U.S. companies’ lobbying efforts). Similarly, economist Joseph Politano finds that the single biggest product excluded from Trump’s tariffs are computers and related equipment, boosting some advanced U.S. manufacturers and helping to fuel the datacenter and AI booms that are keeping the U.S. economy afloat:

Keeping tariffs off these critical goods has undoubtedly been good for the U.S. companies and industries involved, but it raises the obvious questions of why other advanced manufacturers (e.g. automakers) haven’t enjoyed similar treatment and how much they’re being hurt by current U.S. tariffs on the stuff they need. As Politano notes, moreover, the exemptions also contradict the administration’s supposed “reindustrialization” strategy and its clear disdain for freer trade—as Trump’s furniture tariffs make clear:

Paradoxically, the White House is unwilling to use tariffs on the technologically valuable industries because those tariffs come with much larger short-term pain. Domestic electronics production is obviously more important to US national security than furniture production, but America is currently imposing 50% tariffs on kitchen cabinets and 0% tariffs on data center computers because the electronics tariffs would kill the AI boom and furniture tariffs will only raise prices for consumers…. The US is at the technological forefront of a rapidly expanding industry because of the free trade policies that this administration ostensibly despises. It’s just tragic that this privilege is not extended to businesses outside Silicon Valley.

Tragic, yes, but—given who’s undoubtedly lobbying for the tariff exemptions—utterly predictable.

Summing It All Up

The Trump administration and its advocates have long sold tariffs as a smart and necessary way to reindustrialize the country, bolster national security, and revitalize the economy more broadly. In practice, however, they put tariffs on cabinets and sofas for “national security” reasons, exempt others because of potential political blowback, and do all sorts of other things that likely undermine the economic and security objectives the administration says its tariffs are achieving. And they do it all with little regard for the facts, economics, or law.

Throw in some foolish nostalgia (contra the president, furniture manufacturing is today a tiny share of North Carolina’s economy and workforce, and we’re totally fine with that), and the furniture tariffs make for an almost-perfect example of the canyon between protectionist rhetoric and U.S. tariff reality. The only thing preventing perfection is that there isn’t a “national emergency” or fake “fiscal crisis” attached. But we have those tariffs too, of course, and plenty more time to write about them.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.