Dear Capitolisters,

Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in.

Ok, maybe that’s a bit too dramatic, but it’s most definitely how I felt last week when hearing about the latest tariff proposal from former President (and still-GOP-frontrunner) Donald Trump. In particular, multiple news outlets reported last week that the Trump campaign is actively considering a “universal baseline tariff”: a 10 percent “ring around the U.S. economy” that would automatically apply to all imports, regardless of source—and, presumably, above and beyond all the current tariffs already in place. The plan’s details are unsurprisingly non-existent, but Trump did gleefully confirm the idea in a subsequent interview.

If Trump is reelected, of course, the United States likely has bigger problems than tariff policy. (Understatement, I know.) But since economic nationalism remains a bipartisan trend, since nobody on the GOP debate stage seems eager to buck that trend, and since somewhat-more-serious people have floated a similar global tariff plan or defended Trump’s proposal, it’s arguably worth discussing. So, instead of me writing about fun things like Applebee’s or expiration dates or rent control, I get to write about tariffs. Again.

Anyway, as you can probably imagine, I view the Trump tariff plan as economically ignorant, geopolitically dangerous, and politically misguided. And, per those same reports, plenty of other economists, diplomats, lawyers, and trade wonks tend to agree. So, apparently, does the Biden White House. But underdiscussed—if discussed at all—is how the last several years have paved the way for precisely the type of unilateral tariff mayhem that Trump just proposed, and how the Biden administration itself has greatly contributed to the problem.

Newsflash: Tariffs Remain Terrible Policy

Back in this newsletter’s early days, I reviewed the economics of tariffs and the United States’ experiences with them before and during the Trump era, and I’ve done deep dives on China and related tariff stuff both here and elsewhere. So, I won’t dig too deeply into the basics again today. A few points do, however, warrant elaboration in light of recent events and new research.

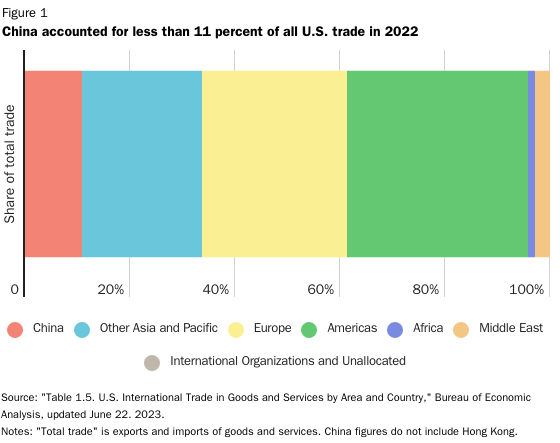

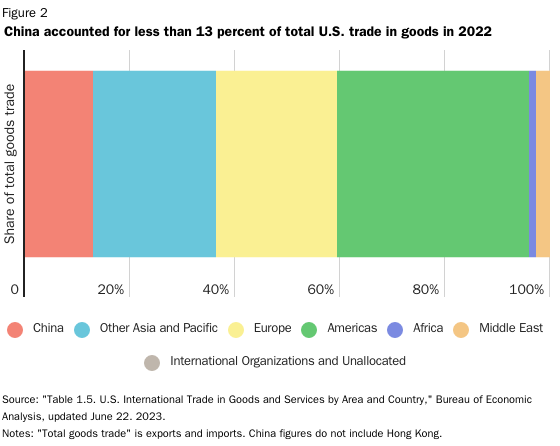

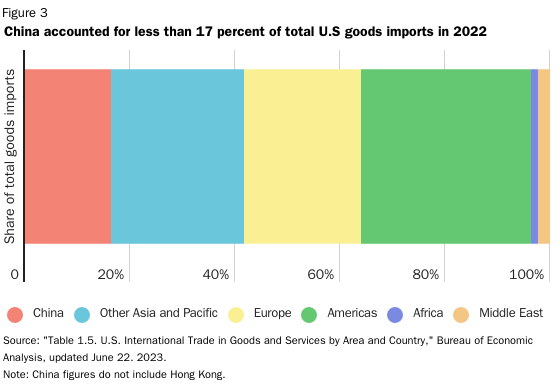

For starters, it’s important to note up front that—contrary to so much of the protectionist spin you read these days, including from the White House itself—the vast majority of U.S. trade (goods and services; imports and exports) involves countries other than China. According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, for example, not-China countries accounted for more than 89 percent of all U.S. trade last year.

The numbers for goods trade (i.e., what would get caught up in any global tariff war) are a little different, but tell the same general story: China is a big U.S. trading partner, but the vast majority of U.S. trade in goods in 2022 involved other countries.

Also contrary to what Trump said last week, the tariffs would have nothing to do with “dumping” (which has a precise meaning and process under U.S. law). Instead, this is just a flat tax on fairly traded imports—mainly from countries other than China. (Indeed, these tariffs could actually make China more competitive vis-à-vis competitor countries, as higher tariffs recently did for certain developing country products that lost preferential access to the U.S. market.)

Second, and contrary to what Newt Gingrich might tell you, the United States’ use of tariffs during the 19th and early 20th century is hardly some sort of ringing endorsement for its use today. As I briefly noted a few weeks ago, research shows that the “American system” of protective tariffs didn’t fuel rapid U.S. growth and industrialization during the 1800s (that was mainly from population growth), but it did fuel rampant political corruption and cronyism in the federal government. (For more on that last point, see this relatively new paper on how lobbying—not economics—determined tariff levels in the infamous Smoot-Hawley era.)

Even more obvious, however, is the absurdity of the still-popular idea that 19th century policy somehow translates to the 21st century global economy. As I explained in a 2017 paper:

We live in a strikingly different world today than the one inhabited by supposed protectionist champions such as Alexander Hamilton and Abraham Lincoln. Trade among nations was far less developed; trade barriers were generally higher everywhere; national economies were much less diversified, reliant mainly on agriculture and only later on some basic manufacturing; communications and shipping were inefficient and costly; and there was no rules‐based multilateral trading system for countries to commit to trade liberalization and for adjudicating disputes. Finally, tariffs were the United States’ only source of revenue, thus limiting legislators’ ability either to zero them out or to make them real and broad‐based barriers to imports.

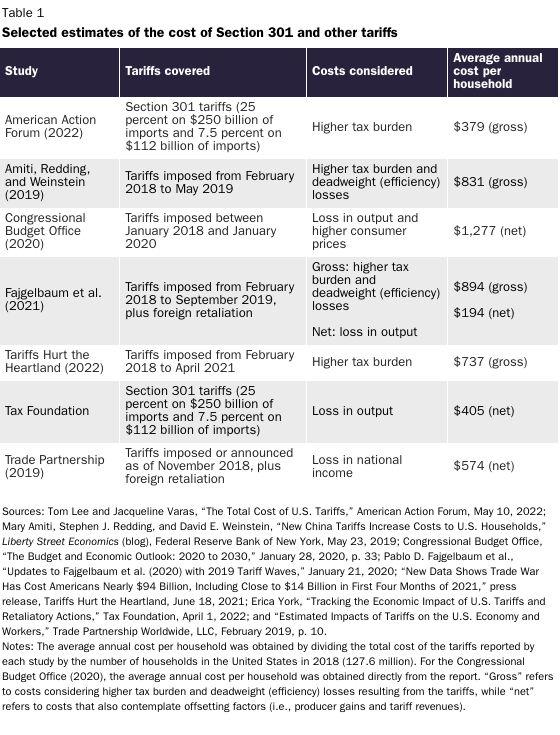

We also, of course, have reams of economic literature and actual experience with tariffs in the modern era—showing not only significant harms but also why 19th century trade policy doesn’t work today. On Trump’s tariffs on steel/aluminum (“Section 232”) and imports from China (“Section 301”), in particular, a recent paper of mine provides a handy summary of this research and the tariffs’ big costs:

Since then, there have been a few important updates. Most notably, the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) published a big report earlier this year on the economic effects of the Trump-era tariffs. Confirming the results from the reports noted above, the USITC found that these tariffs 1) were paid by American importers and consumers (not “China” or foreign exporters); 2) increased U.S. prices of both imports and domestically produced goods; 3) hurt American manufacturers in industries (automotive, machinery, appliance, etc.) that rely on tariffed inputs; and 4) actually reduced overall U.S. manufacturing output by billions of dollars per year, because these downstream harms far outweighed benefits to protected U.S. companies.

A year earlier, a group of International Monetary Fund economists examined how recent U.S.-China tariffs affected trade and economic welfare in today’s more integrated world of interlinked multinational supply chains (i.e., not the 1800s). They found that “tariffs higher up and further down in the value chain depress value added, employment, labor productivity and total factor productivity to varying degrees,” while providing “no benefits for the sector that enjoys additional protection.” The harms were magnified by the existence of global supply chains—something that didn’t really exist 150 years ago. The only beneficiaries were countries not involved in the trade war (who replaced tariffed products with their own). And just this week, a group of academic economists found that Trump-era tariffs likely caused many U.S. importing companies to exit the market altogether while also reducing these globally-integrated firms’ exports (because they had higher input costs).

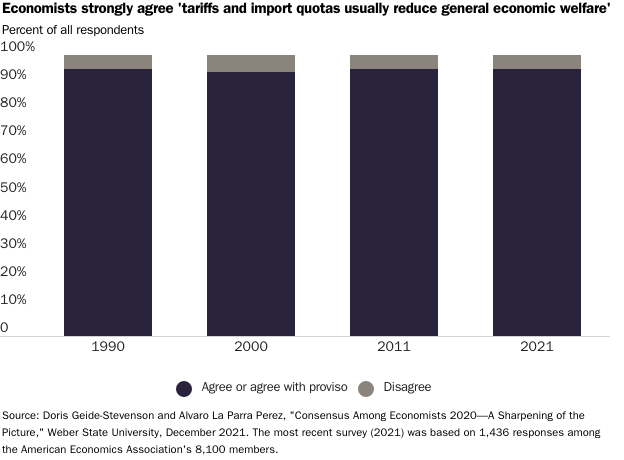

Throw this new research onto the mountain of other research showing tariffs’ harms and complicated history, and hopefully you can see why endorsing global tariffs today because certain early American heroes liked them is pretty silly. We have plenty of receipts, and things have changed. A lot. And, as I noted a few years ago, these facts are a big reason why economists almost uniformly view tariffs as welfare-reducing policy—“strong agreement” once again confirmed in this recent survey of more than 1,400 of members of the American Economics Association:

Experts Have Unsurprisingly Panned Trump’s Tariff Plan

Given the research and history, it’s unsurprising that Trump’s global tariff idea was met with immediate disdain by trade-policy experts on the left, right, and center. George Mason economist Don Boudreaux called the proposal’s motivations an “utter mystery.” Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, said the “horrifying” proposal was “lunacy” that would harm U.S. consumers, import-using industries, and exporters while undermining Washington’s credibility around the world. Paul Krugman (who remains a good trade economist, for all his other warts) said much the same thing. Dartmouth’s Doug Irwin (who wrote the book on the history of U.S. trade policy) focused on the painful retaliation other nations would inevitably pursue (as they did when Trump imposed his other tariffs) and suggested it’d kill the already-crippled World Trade Organization. Playing off Irwin’s comments, trade economist Bob Koopman pointed to his latest research, showing how this kind of global trade fragmentation would be bad for the U.S. economy, but really, really bad for smaller, poorer countries that have yet to fully reap the benefits of open trade and globalization more broadly. Heck, even the deputy director of Trump’s own Domestic Policy Council, Paul Winfree, panned the tariff proposal, saying it “would impose a massive tax on the folks who it intends to help.”

Adding up these harms, the Tax Foundation’s Erica York calculates that the Trump tariff “ring” would amount to a $300 billion annual tax hike, reducing the size of the U.S. economy by 0.7 percent and eliminating 505,000 jobs. She notes that—again consistent with plenty of research and recent history—these harms would occur through a combination of higher prices for companies and consumers and a stronger dollar (which would offset some consumer pain but in the process make U.S. exports less competitive abroad). And if the rest of the world retaliated in kind (as most of them would), U.S. GDP would shrink by another 0.4 percent, and an additional 322,000 jobs would be lost. York thus concludes:

We know from decades of experience and evidence that tariffs reduce employment, productivity, and output. The past five years have demonstrated that reality all too well. During his term, Trump imposed nearly $80 billion of tariffs on steel, aluminum, solar panels, washing machines, and thousands of products from China. President Biden has largely maintained them. The result? They have destroyed U.S. manufacturing jobs, harmed U.S. farmers, raised prices for U.S. consumers, and alienated our allies—all without changing China’s unfair trade policies or reviving protected domestic industries. It appears the lesson has not been learned.

So here we are.

The Biden White House’s Criticism—And Responsibility

The Biden White House has also criticized the Trump tariff proposal: Because it’d “hurt hardworking families with higher prices and higher inflation” and “stifle economic growth,” a spokesman said, the president “strongly opposes” a global tariff and will instead continue to “work with allies” against China and other trade scofflaws.

It’s nice to see President Biden’s words acknowledge these realities; his actions, on the other hand, leave much to be desired.

As we’ve discussed, for example, the Biden administration has barely touched Trump’s Section 232 and Section 301 tariffs, even though the president could remove them all with the stroke of a pen. The White House has also doubled down on protectionist Buy America rules, the Jones Act, and new domestic content mandates and subsidies for federally funded renewable energy and infrastructure projects—none of which target just China, by the way. And, far from being embarrassed about these actions, the administration—even Biden’s trade representative!—is bragging about them in advance of the 2024 election:

But the president hasn’t just endorsed and implemented specific protectionist laws during his first three years in office; he’s also actively worked to give himself—and any future president—even more protectionist power under these same laws.

First, the Biden administration has vigorously defended Trump’s tariffs in U.S. courts. As I explained in recent papers on the Section 232 tariffs and the Section 301 tariffs, the Trump administration cut procedural and substantive corners—often blatantly—when implementing and modifying the tariffs between 2018 and 2020. In one particularly egregious example, Trump unilaterally doubled the Section 232 tariffs on Turkish steel long after the statute’s deadlines for taking such action, and he expressly did so for reasons unrelated to those supporting the steel tariffs (to pressure the Turkish government on a diplomatic matter, not to boost the U.S. steel industry). In carrying out this shenanigan and others, the administration also exposed important flaws in both laws and raised bigger questions about whether the laws themselves were a proper delegation of Congress’ trade powers under the Constitution.

As a result, multiple U.S. companies have challenged various aspects of the tariff investigations and proclamations, as well as their constitutionality and compliance with the Administrative Procedures Act, which disciplines the actions of all U.S. agencies. And they’ve had varying levels of success in doing so—mainly losing on the substantive and constitutional cases but scoring early wins on some of the nitty-gritty procedural challenges. Many of these cases have then been appealed and were still ongoing when Biden took office in 2021.

The cases thus presented the Biden administration with an ideal opportunity to passively reduce or even eliminate the Trump tariffs by simply choosing not to defend them in court—similar to how they handled other pending court challenges to Trump-era policies (like this one on immigration). They might have even gone a step further and let the bigger legal challenges proceed unabated, thus defanging these problematic laws and protecting American companies and consumers against future presidential abuses.

They’ve done no such thing.

In fact, the Biden administration has fought essentially every U.S. court challenge to the Trump-era tariffs and the U.S. laws that he abused to implement them. They’ve done this when the government has won, and when it’s lost—fighting to keep the tariffs in place, to defend the almost-limitless discretion that these laws afford to the president to impose tariffs, and to ensure that the courts broadly defer to the executive branch’s implementation of these laws. I won’t bore you with all the details, but here are a couple quotes so you get the idea:

- November 2021: “Instead of taking his own actions to undo an unlawful order from the former chief executive, President Joe Biden had the government’s attorneys argue in favor of even greater trade powers for the White House.”

- August 2022: “The U.S. government defended additional tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars of Chinese goods imposed under Donald Trump.”

- February 2023: “The Biden administration urged the U.S. Supreme Court not to touch former President Donald Trump’s controversial tariffs on steel imports.”

The executive branch has similarly fought limits on U.S. government protectionism under existing international agreements. As we discussed late last year, for example, the White House has continued Trump’s neutering of the World Trade Organization Appellate Body (which adjudicates government-to-government disputes) and went so far as to openly refuse to acknowledge the WTO panel ruling against the Section 232 tariffs. The White House has also refused to comply—for almost a year now—with a 2022 USMCA panel that ruled against the United States’ more restrictive interpretation of rules governing North American automotive trade.

But it’s not just protectionism in which the Biden administration has sought to expand the president’s powers under existing U.S. trade laws. As the Council on Foreign Relations’ Inu Manak has explained in several recent pieces, for example, the executive branch has repeatedly ignored the content and spirit of U.S. law (and the Constitution) when implementing—not just negotiating—new trade agreements (e.g., on “critical minerals” or Taiwan) without congressional approval. They’ve also sought to further expand Section 232—and the metals tariff proclamation—by using it as a pretense to negotiate an agreement with the European Union and others on carbon-intensive steelmaking (including domestic policies in support of this environmental initiative).

Thus, in case after case and venue after venue, the White House has consistently prioritized not only American protectionism but also executive branch discretion and power to implement more of it in the years ahead.

So Here We Are

Congress, of course, isn’t exactly blameless here either. Ever since Trump took office and legal experts realized that U.S. trade law is littered with old, ambiguous statutes that could be abused by a president with little regard for economic history or legal norms, legislation has been offered to reform the underlying laws or provide a congressional check on their use. (See, for example, Sen. Mike Lee’s Global Trade Accountability Act or the bipartisan Bicameral Congressional Trade Authority Act, which had around 20 cosponsors.) Congress hasn’t advanced these measures, and the White House hasn’t asked them to, either.

So, now we’re in the heat of a presidential election with the two top candidates running a politically motivated protectionist race to the bottom, and U.S. trade law is just as broken and open-ended as it was the day before Donald Trump ever took office—more broken and open-ended, in fact, because the Biden administration’s court victories establish precedent that makes future legal challenges more difficult.

Trump’s tariff proposal is bad, and in a saner world it’d be so relentlessly criticized and mocked as to disappear mere moments after it was first floated. But we don’t live in that world right now; tariffs—in whatever form, whether implemented by Trump or another president with his penchant for the policy tool—remain a risk, and, contrary to what the White House might tell you, we have Joe Biden to thank for it.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.