Last week, Republican vice presidential candidate J.D. Vance made a bold claim about the Trump campaign and today’s Republican Party. Speaking to a boisterous crowd in Henderson, Nevada, Vance went on an extended spiel about the U.S. economy and the “American dream,” at one point declaring that Republicans “believe that a million cheap knockoff toasters aren’t worth the price of a single American manufacturing job.” The crowd, quite predictably, cheered.

As I and others remarked at the time, Vance’s comment—taken literally or figuratively—makes little economic sense. Even ignoring that falling prices of household necessities (aka “toaster abundance”) are to be celebrated, or that Trump’s tariffs have actually harmed American appliance-makers, Sen. Vance is championing an utterly absurd American jobs program. The cheapest toaster at Walmart costs about $10, so blocking one million of them would mean that the senator believes American taxpayers and consumers should bear $10 million (or more?) in additional economic costs to save a single U.S. job making toasters—a job that’s, to put it nicely, not exactly strategic, high-tech, high-paying, or in high-demand among American workers. (Lower-skill manufacturing positions today generally pay less than $1,000/week, and U.S. manufacturers continue to report difficulties finding staff.) Trim the figure to, say, $2 million, and we’re still looking at a cost/benefit situation that’s far more economically painful than even the most onerous U.S. protectionism.

What is third-party litigation funding?

Of course, Vance’s toaster comments had nothing to do with economics and everything to do with politics—in particular the current, unquestioned conventional wisdom that Americans (especially Republicans) have passionately turned en masse against trade and globalization, and that winning U.S. elections requires a heavy dose of economic nationalism, regardless of its actual costs. Indeed, if you were to read the political press or listen to our presidential candidates, you’d be forgiven for thinking that Americans really are all protectionists today.

I’ve long been skeptical of this narrative and, after examining the available polling on trade and globalization, wrote as much back in 2018 when Trump first started imposing his tariffs (and when pollsters’ attention first turned to the issue in-depth). Back then, however, I found the polls to be lacking—setting up false choices (e.g., do you like imports OR exports?), failing to probe real-world trade-offs or partisan biases, or just being poorly-worded. Subsequent polls have suffered from similar problems or have been issued by folks with an obvious, usually anti-trade, agenda.

So, Cato’s in-house pollster Emily Ekins and I wrote our own questions and commissioned our own nationwide survey (with help from polling outfit YouGov), the results of which we released today—results that contradict much of what you hear about Americans’ views on trade and globalization.

To be clear, it’s not all good. The 2,000 Americans we polled aren’t committed Hayekian free traders (LOL). They think some wacky things about economics and policy. And they do have an affinity for tariffs, U.S. manufacturing, and buying American.

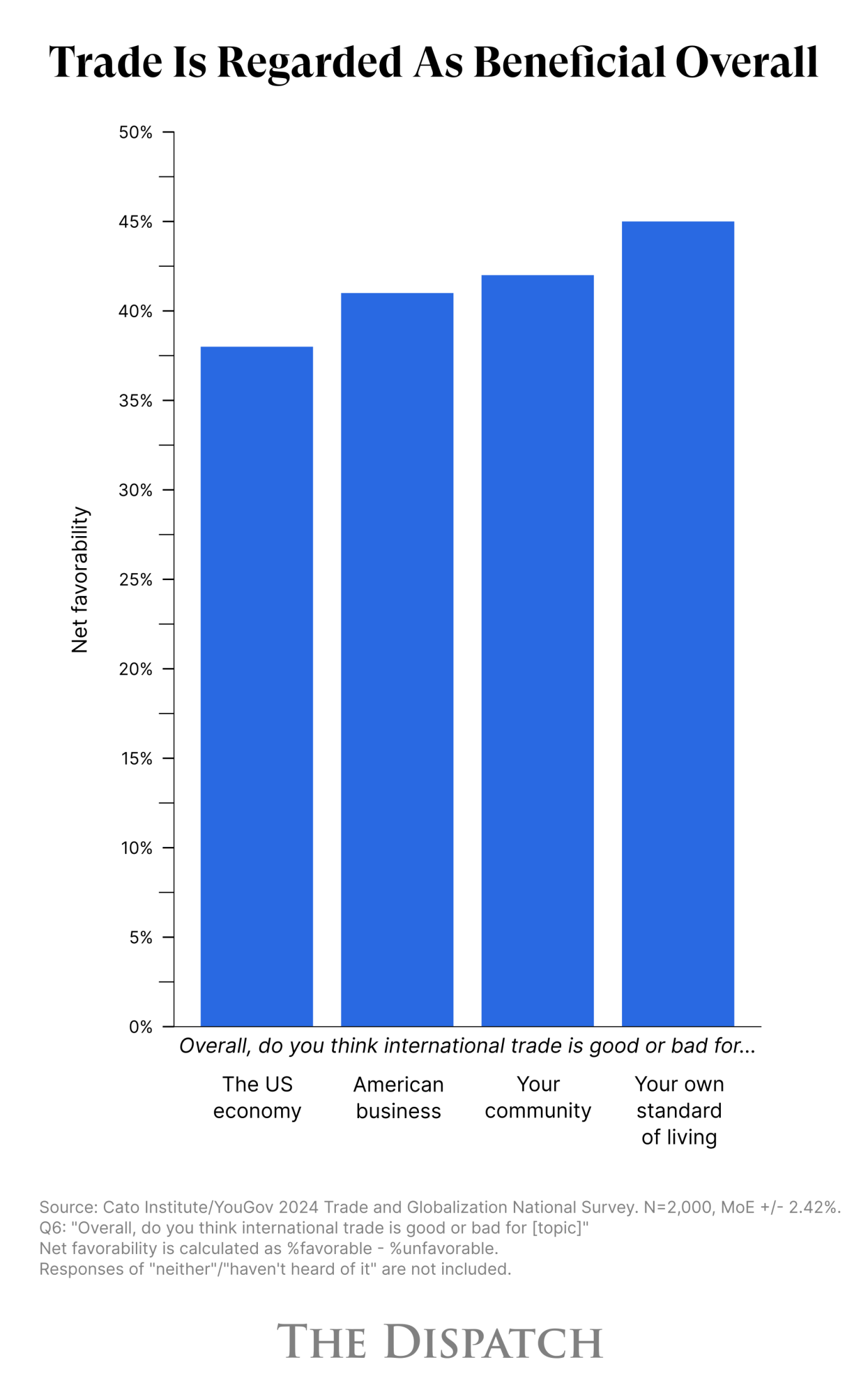

Yet they also support trade and trade agreements (and even “globalization”) by large margins and tend to think that trade has been mostly good for their own living standards, for their communities, and for the nation. (Even Trump voters or people with less education and income think this, by the way.) And, most important for today, poll respondents reverse their nationalist preferences when faced with the economic and practical realities that usually accompany American protectionism. Especially its price tag.

For example, 50 percent of Americans, 59 percent of Republicans, and 62 percent of Trump 2020 voters say they support tariffs generally. However, more than 70 percent of each group also says that they’re “concerned … about rising prices of things you buy because of trade tariffs.” About half of respondents also would favor “Congress eliminating all tariffs on food, clothing, and shoes made in other countries to reduce prices Americans pay for these items.”

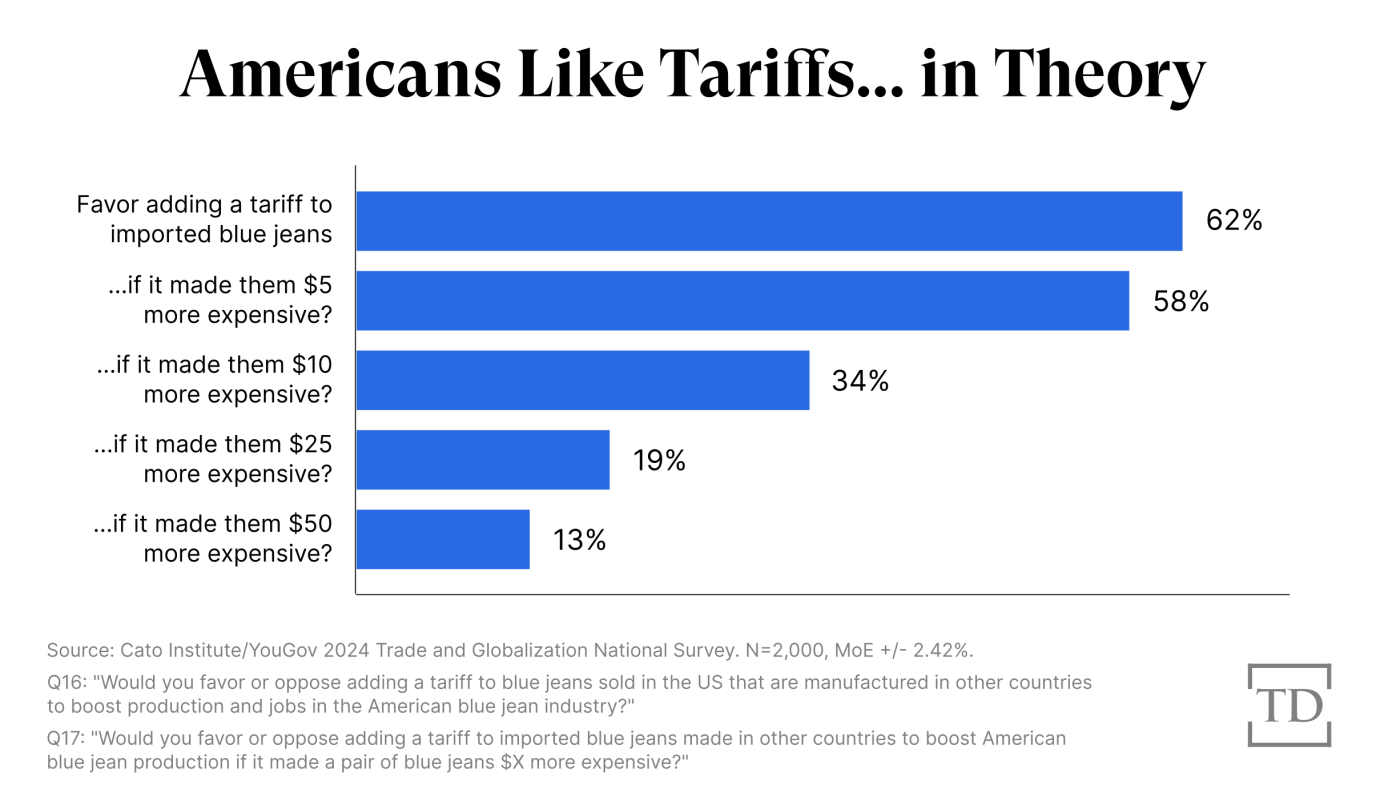

Things get even more interesting when we put a specific price on U.S. protectionism, with most respondents unwilling to pay more than a pittance for it, even when tied to American manufacturing jobs. We asked, for example, whether respondents would support tariffs on blue jeans to “boost production and jobs in the American blue jean industry,” and they were initially quite supportive (62 percent in favor). But then we asked the same question with the inevitable trade-off—higher blue jean prices—and support collapsed.

More than 65 percent of all Americans polled (and almost 60 percent of self-identified Trump voters) would oppose the tariffs if they made jeans cost just $10 more. This opposition rises to 81 percent (76 percent for the Trump folks) at $25. For reference, American-made jeans cost $100 to $200 per pair, while a decent pair of imported Levi’s 501s are half that amount. So, a $25 tariff bump is certainly not out of the question here.

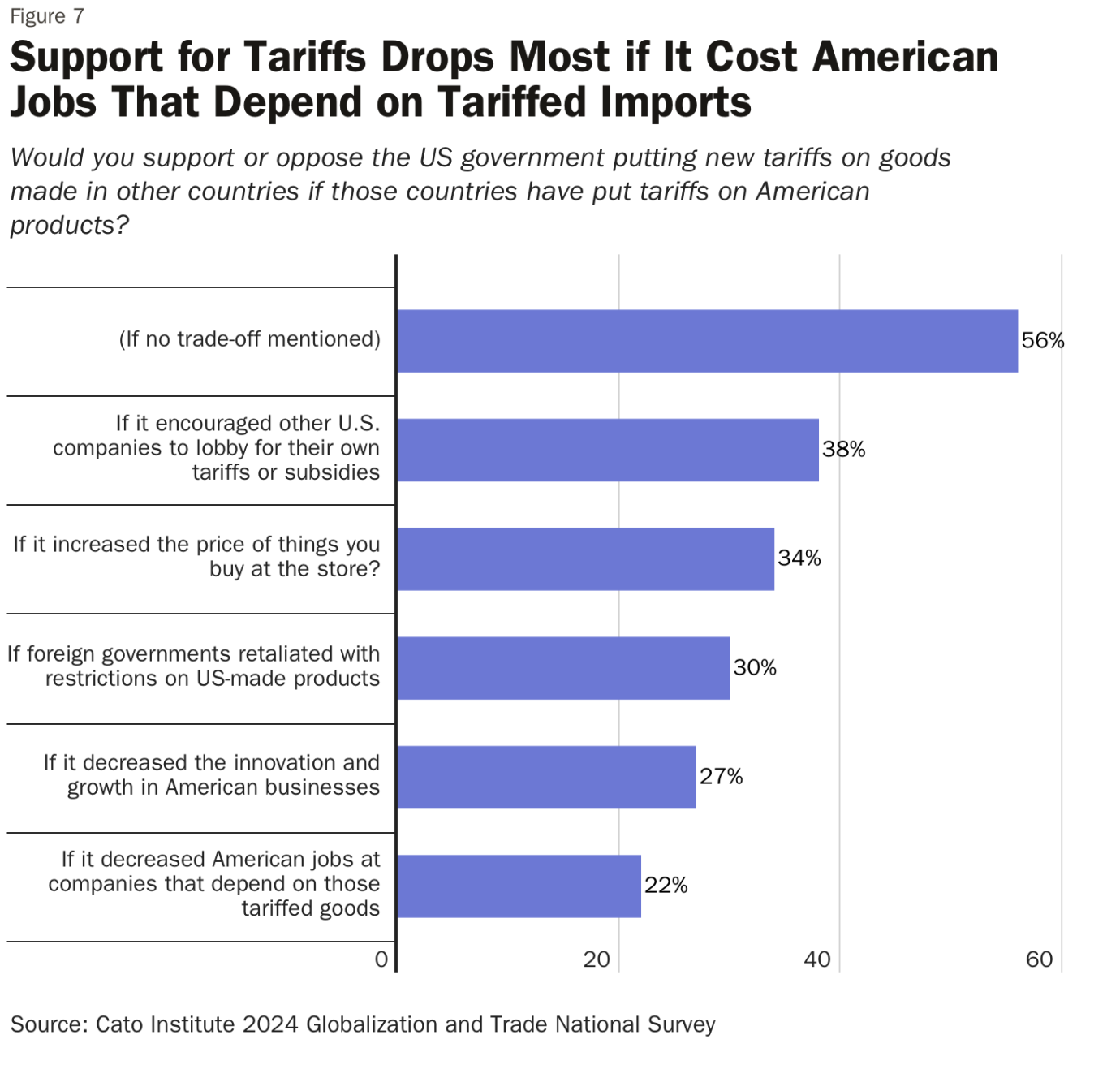

Support for blue jean tariffs also dropped significantly when we raised the prospect of foreign retaliation, with 51 percent of respondents now opposed. And for tariffs generally, Americans’ initial support craters when these and other trade-offs are mentioned in the poll question:

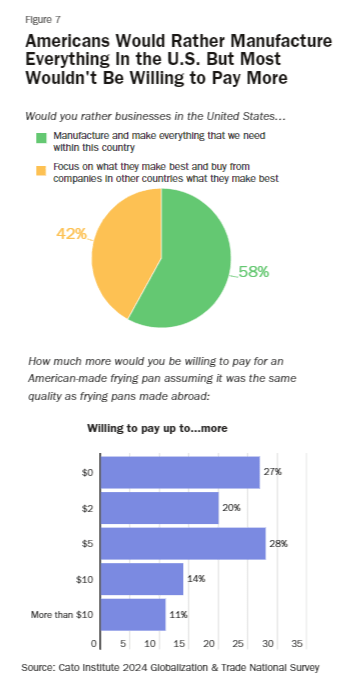

“Buy American” policies suffer a similar fate. When we asked if respondents generally preferred to buy made-in-USA products, a whopping 75 percent said yes. But then we asked when they last “purposefully bought American-made products,” and only 24 percent (30 percent of Trump voters) said they’d tried in the last week—and almost half hadn’t tried to buy American in the last year or longer. Cost also again looms large here: At least 70 percent of all respondents, including Republicans and Trump voters, reported that they’d be unwilling to pay just $10 more for “an American-made frying pan assuming it was the same quality as frying pans made abroad.” (Spoiler: it’s probably gonna cost more than that.)

In short, J.D. Vance might be willing to pay the cost of our Glorious American Toaster Autarky (or whatever), but few of the folks cheering him would actually do the same.

So, Why Do They Cheer?

Combine these and other nuggets in the poll with Americans’ general support for international trade (see next charts), and it raises the obvious question: Why do Americans—especially after just coming off a miserable bout of inflation that everyone hated—cheer lines like Vance’s and generally support politicians like Trump and Biden who constantly champion costly economic nationalism?

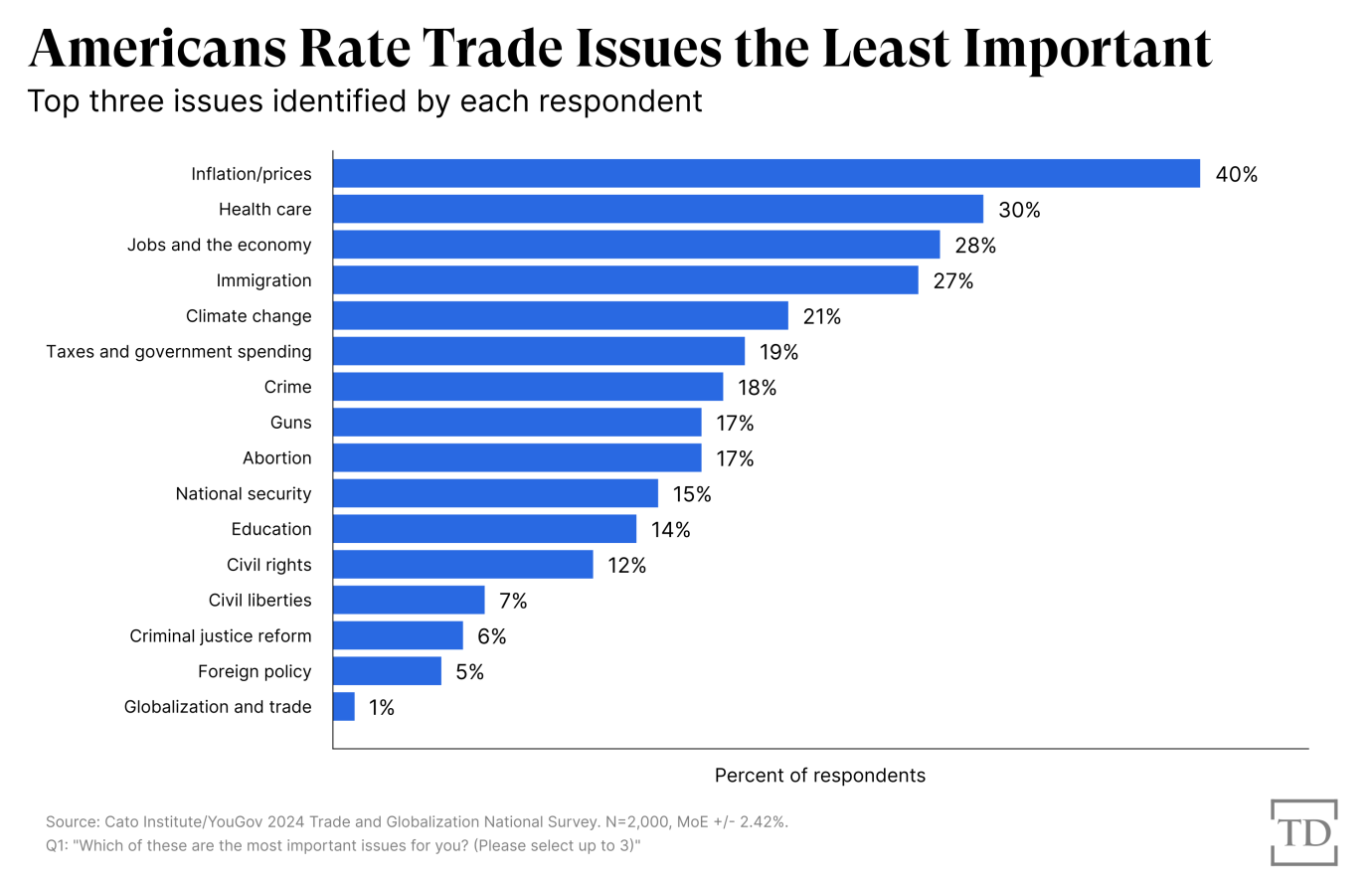

I see several reasons. Most basically, trade is complicated, counterintuitive, and full of “unseen” benefits and costs that aren’t normally taught outside of an economics classroom (or Capitolism newsletter). And globalization plays into all of the innate biases—about foreigners, the status quo, the market, and “jobs”—that we humans have about the world around us. Furthermore, the vast majority of Americans have no direct personal connection to or experience with international trade. Most of us work in non-tradable services and, contrary to what you might hear, the United States is one of the least trade-dependent economies in the world. Finally, and probably thanks in part to the previous points, we don’t care at all about global trade, with respondents consistently ranking it at the bottom of their policy priorities. Here’s our poll’s list, with trade at the bottom:

As a result of these factors, Americans don’t know much about trade and don’t spend much time learning about it—a textbook case of “rational ignorance.” Instead, our views are often superficial, incoherent, and/or driven by things other than trade—like culture, patriotism, politics, media, or the state of the U.S. economy.

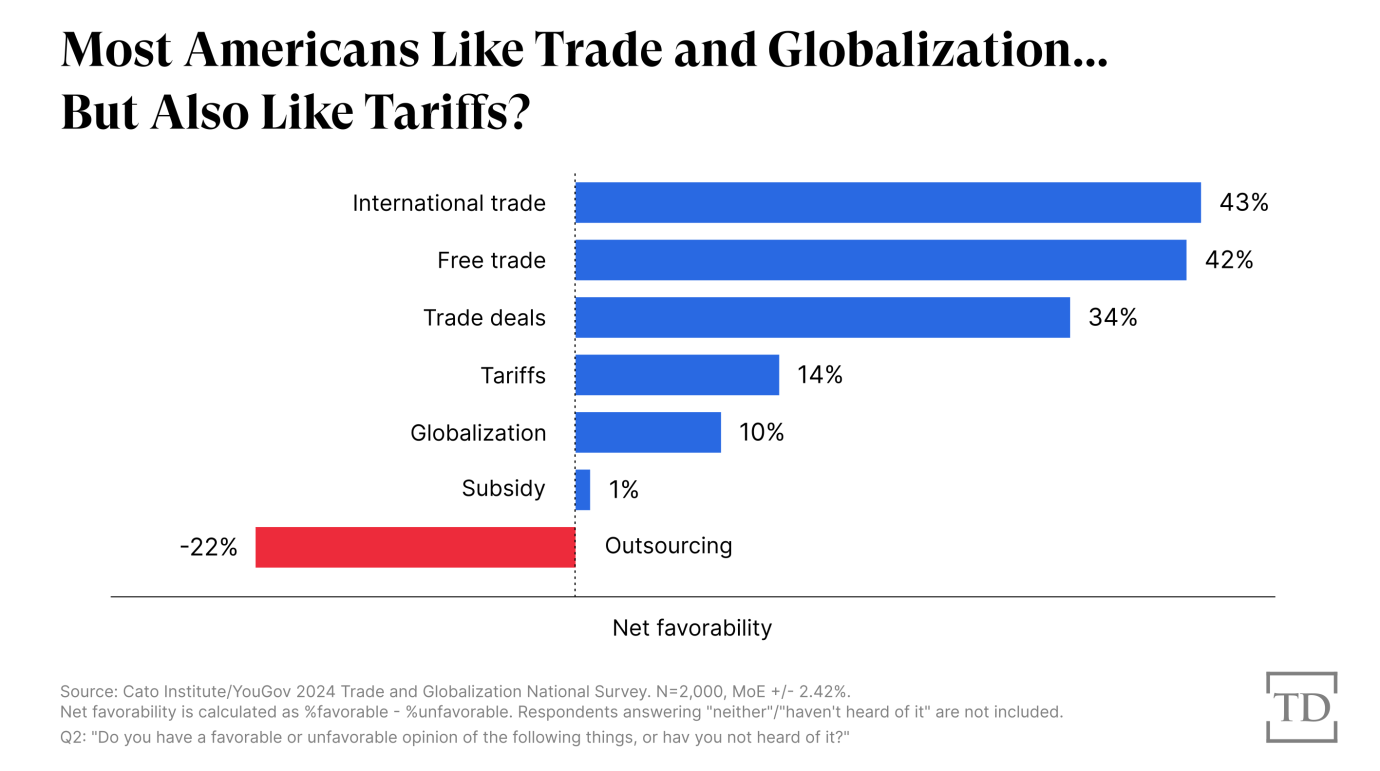

Our new poll shows all this stuff. Respondents say they like free trade and trade agreements but also say they like tariffs that “protect jobs” or police “unfairness.”

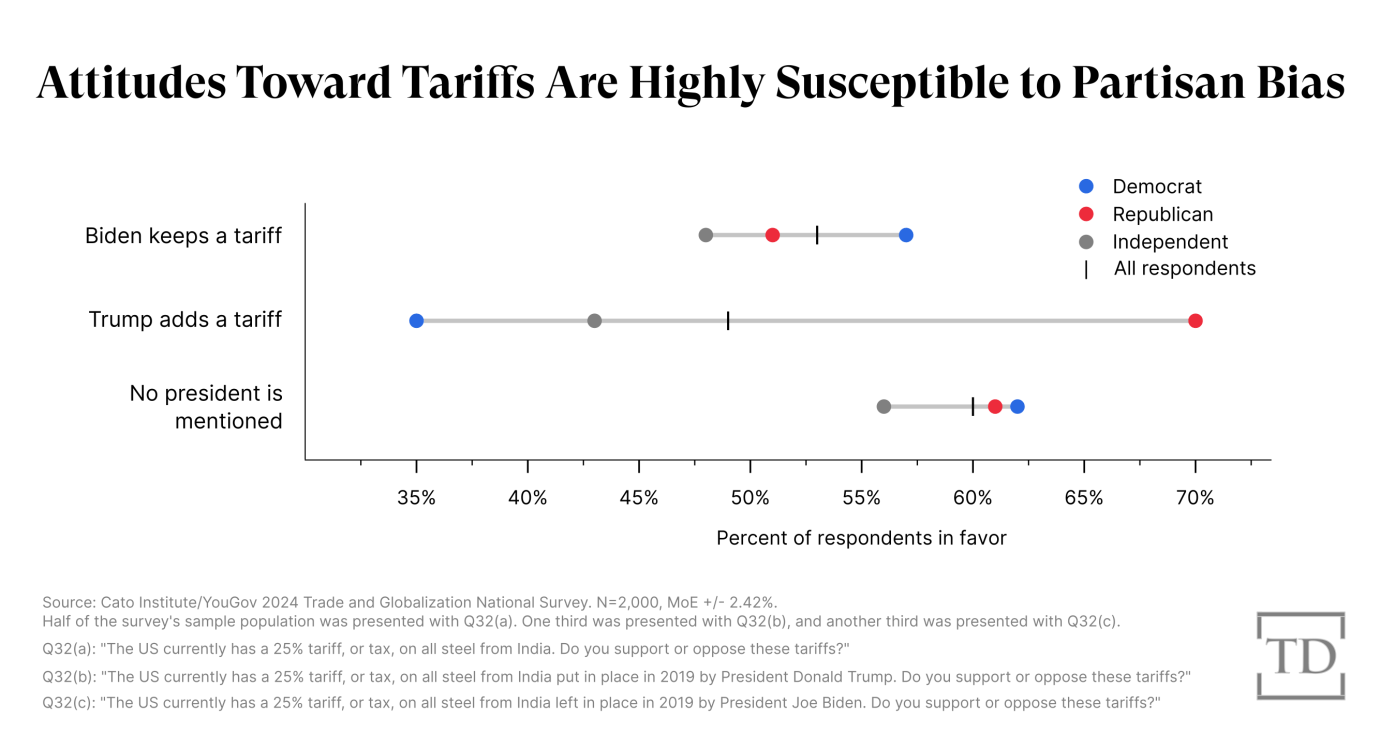

Most of them wildly overestimate how much stuff we import from China and wildly underestimate how automation has affected manufacturing jobs. Only 47 percent correctly think that U.S. tariffs are primarily paid by American consumers (sigh). And substantial chunks of both Republicans and Democrats predictably change their views on U.S. tariffs when we attached Biden’s or Trump’s name to them.

In case after case, it’s clear that respondents aren’t thinking deeply about these issues and are instead swayed by other things. And, to be clear, that’s totally fine—we all have busy lives and most of us have better things to do than learn international economics. But it’s a lot less fine for politicians, pundits, and wonks—people who should know better—to use these gut feelings to push national policy and broad, enduring, and usually self-serving narratives about the American electorate.

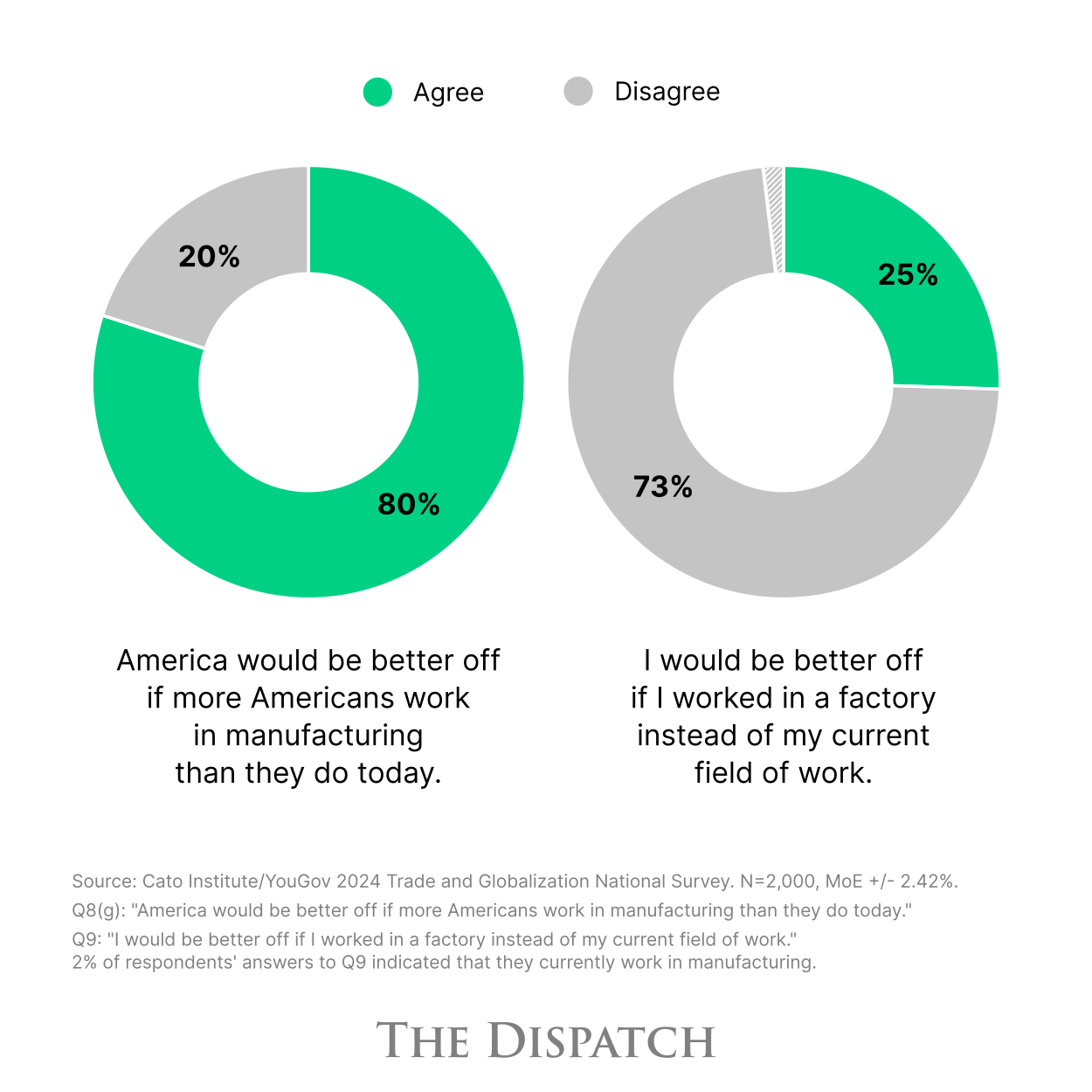

This same dynamic further explains why Americans’ stated preferences (“Buying American is great!”) often greatly diverge from their revealed preferences (“But I don’t actually try to buy American!”) and why our views on trade and globalization often change radically when confronted with basic facts and the inevitable trade-offs that affect us personally. In one of my favorite examples, we find that 80 percent of people in our poll agree that more Americans should work in manufacturing, but that 73 percent of those very same people disagree that they personally would be better off working in a factory. (It’s in the mid- to upper-60s for respondents with less income or education.) For the vast majority of Americans, shift-work down at the Ol’ Mill sounds great… unless you’re the one doing it.

People also really worry about the terrible-sounding trade deficit—until you teach them the iron law of Econ 101 that almost every dollar we send abroad for imports eventually makes it back to the United States (either to buy U.S. exports or as investment in the economy):

Overall, the responses paint a very different picture of the American electorate from the one we’re told so obviously exists today. Not necessarily an inspiring one, but definitely different.

Summing It All Up

So where does that leave us?

Well, for free traders like me there’s both good and bad news in the results. On the former, it’s (again) clear that large chunks of the American electorate generally like trade and globalization and respond favorably when confronted with the facts or protectionism’s real-world costs—higher prices, foreign retaliation, increased cronyism, lost jobs in import-consuming industries, etc. An aspiring wonk or policymaker could thus use these results (and others in the poll—see toplines and crosstabs) to craft a winning free-market message—if, of course, she or he is willing to put in the effort.

Local politics and electoral maps of course matter too, but, as a general matter, supporting globalization is not the political death-knell it’s so often made out to be in the United States today. Principled politicians may therefore feel freer to adopt trade policies based on the actual facts and economics, not some misplaced fear of electoral doom and national ridicule. (Whether they actually will is another matter.)

On the bad news side, trade is clearly susceptible to intense, often-ridiculous demagoguery of the type we see regularly today—and saw at that Vance rally last week. Two recent papers show, moreover, that said demagoguery can be effective, in terms of both shaping public opinion and winning actual votes.

- The first finds that many Americans—especially ones with strong views about meritocracy and the “American dream” that Vance expressly mentioned—increasingly adopted anti-globalization views as political elites increasingly blamed “unfair” trade for domestic economic problems. According to the authors, “the more elites argued that other nations’ trade practices were deviating from market principles and hurting hard-working Americans,” the more these American “meritocrats” said that trade and globalization were “bad for the country.” These findings thus explain “why certain groups became critics of globalization” and demonstrate “the importance of elite messaging in defining policy interests even amongst those who are not necessarily directly impacted by the international economy.”

- In the second paper, the famed “China Shock” crew found that Trump’s tariffs didn’t actually boost jobs in “left behind” localities but did modestly boost voter support for Trump and local Republicans. Foreign retaliation, in fact, “had clear negative employment impacts” in these places, but “consistent with expressive views of politics, the tariff war appears nevertheless to have been a political success for the governing Republican party.”

Neither result bodes well for good trade policy or politics in the immediate future, but—just as I wrote in 2018—it’s also clear that most American protectionism today originates in our political class (politicians, lobbyists, connected interest groups, etc.) as opposed to being a response to some sort of broad-based groundswell of American economic nationalism. It’s top-down, not bottom-up, and thus remains a classic example of how “concentrated benefits and diffuse costs” can motivate politicians to champion policies like Vance’s Toaster Autarky that, if enacted, would actually be opposed by most voters—if they understood them.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.