Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

You’re reading Capitolism, Scott Lincicome’s weekly newsletter on economics. To unlock the full version, become a Dispatch member today. This month you can try 30 days of membership for $1.

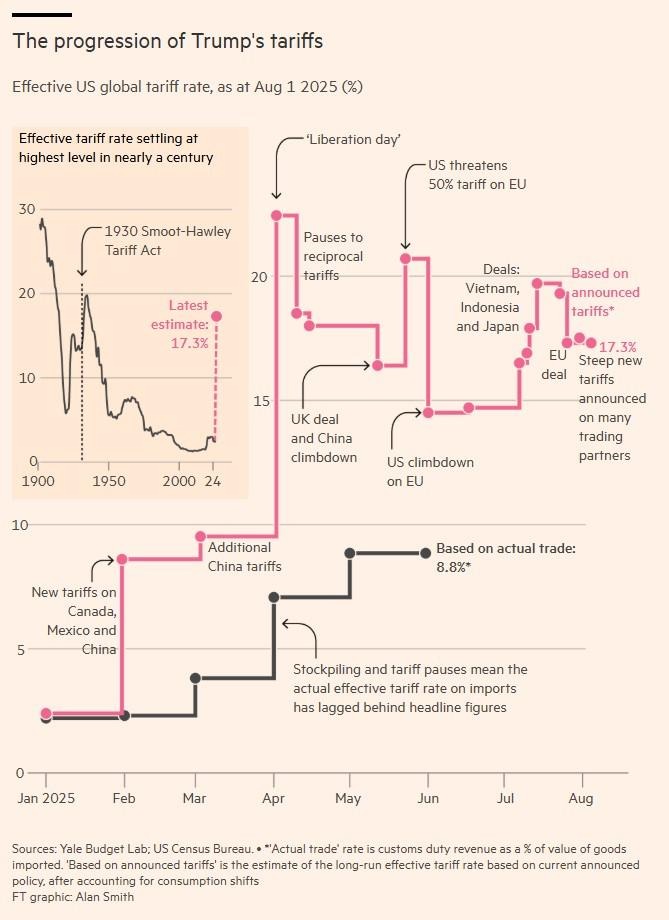

Looking back on this year (as one does in December), there’s been an undeniably huge amount of virtual ink—from Capitolism and everyone else—devoted to U.S. tariff policy. This, of course, is perfectly understandable given the major recent changes to said policy, the tariffs’ substantial economic, political, and diplomatic implications, and the fact that a certain president can’t stop talking about all of it. Indeed, with average U.S. tariff rates now having reached historically high levels via an erratic and endless series of executive branch proclamations and trade deals (as the chart below from the Financial Times indicates), a lack of such coverage would be downright scandalous.

Nevertheless, even the best U.S. tariff analyses have typically focused on the big picture—average tariffs, big deals, major actions or exemptions—while ignoring an issue that’s just as important, if not more so, for the tens of thousands of American businesses now forced to grapple with U.S. tariffs every day: their unprecedented, crippling, and truly insane complexity. Beginning in Trump’s first term and dramatically accelerating this year, navigating the U.S. tariff system has gone from relatively easy to mind-numbingly difficult for even the most skilled technicians and biggest corporations. For the little guys, on the other hand, it’s become virtually impossible. And the overall economic cost is likely staggering.

You are receiving the free, truncated version of Capitolism. To read Scott’s full newsletter—and unlock all of our stories, podcasts, and community benefits—try a Dispatch membership for a month for $1.

Stories We Think You’ll Like

Can the Abundance Movement Psyop America Into Sanity?

I found the Abundance 2025 conference buzzing with good people, smart policy ideas, and optimism. It made me depressed.

What About the Poor?

In discussing what’s wrong with capitalism, its effect on poverty is left out.

Regulations Can Create the Monopolies They’re Meant to Prevent

Regulatory complexity can create barriers to entry and compliance costs that hamper competition.

Charting U.S. Tariff Complexity

The chart above is admittedly cool, but by focusing on just average tariff rates, it arguably hides as much as it reveals. That’s because U.S. tariff rates aren’t just one number but instead vary widely by product, country, and the legal regime under which these taxes have been applied, and such differences—as well as how they came about—matter a lot for any U.S. business buying stuff from abroad.

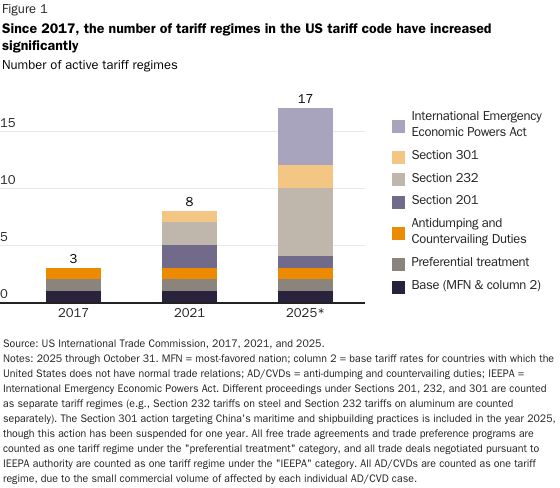

Some variation has always been part of the tariff system, but it has radically increased in recent years, burdening American businesses along the way. Before Trump’s first term in office, U.S. importers typically reviewed three things when calculating their products’ potential tariff liability: 1) the “general” baseline tariffs set in the U.S. tariff code (aka the harmonized tariff system of the United States, or “HTSUS”), which applied uniformly to most countries; 2) “special” exceptions to the baseline rates for a few nations and products subject to preferential arrangements like free trade agreements (also listed in the HTSUS); and 3) for an even smaller number of products (around 1 percent of all imports, as of 2022), whether any additional duties applied because of U.S. antidumping or countervailing duty measures intended to offset “unfair” foreign trade practices. Each of these tariff regimes had its rules and complexities (especially AD/CVD), but they were relatively clear and static—for example, items 1 and 2 are published in the HTSUS for every product, and free online tools let importers determine a product’s detailed tariff code. As a result, even high U.S. tariffs (e.g., on shoes) have long been surmountable by smaller, less sophisticated American businesses, assuming they were willing to pay whatever taxes applied.

The Trump 1.0 and especially Trump 2.0 eras have obliterated this dynamic. During his first term, Trump applied tariffs under three rarely used statutory provisions—Section 201 (global safeguard measures on solar panels and washing machines); Section 232 (global “national security” protection for steel and aluminum); and Section 301 (targeting around half of all Chinese imports). During just the first year of Trump’s second term, he’s added even more Section 232 actions (automotive goods, copper, wood, and trucks/buses), another Section 301 action (on ships), and several rounds of tariffs under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (global “reciprocal” tariffs; fentanyl tariffs for China, Canada, and Mexico; extra punitive tariffs for Brazil and India; and around 10 IEEPA-related trade deals). As of today, 17 different U.S. tariff measures and seven different legal regimes now apply to significant commercial volumes of imports into the United States—up from just three in 2017:

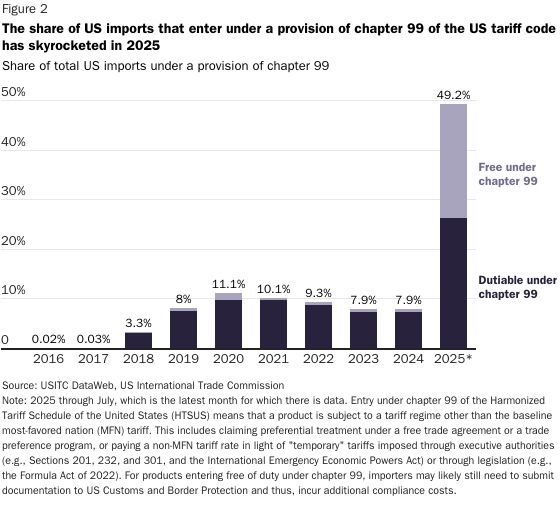

Meanwhile, the total volume of imports now subject to one or more special tariff measures (designated in “Chapter 99” of the HTSUS and covering almost all of Trump’s unilateral tariffs) went from basically nothing in 2017 to almost half of all U.S. imports as of July of this year:

The direct tax burden these tariffs place on American companies has been widely discussed and is undoubtedly significant (roughly $30 billion per month at last count). Less discussed, however, is a regulatory burden that’s at least as substantial.

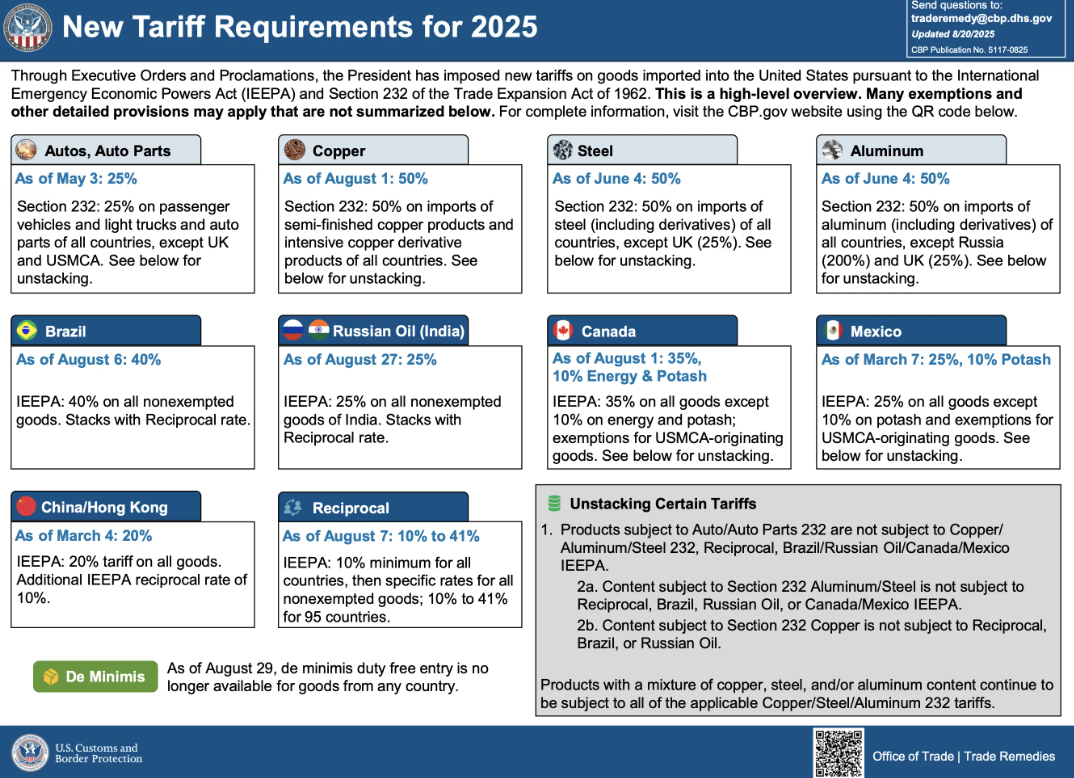

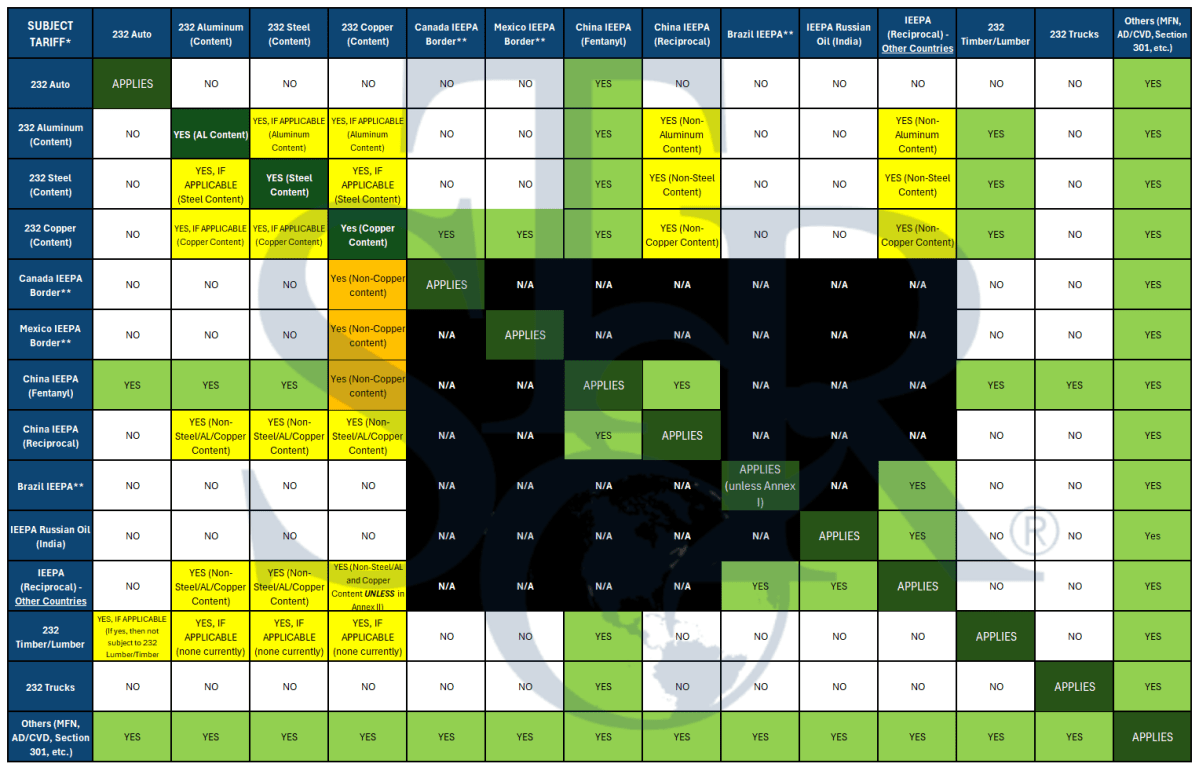

First, each special tariff measure comes with its own legal rules, procedures, exceptions, and reviews—brand new regulations that demand American companies’ finite time, money, and attention. Second, the specific design of Trump’s tariff measures amplifies this complexity because—again, unlike the pre-Trump era—the tariffs can vary not only by country, product, and content, but also by how these tariffs interact with each other. IEEPA “reciprocal” tariffs, for example, apply a different baseline rate for imports from dozens of countries; these tariffs are typically added (“stacked”) on top of the general HTSUS tariffs but not for certain “trade deal” countries (which have negotiated different arrangements). They also stack atop other IEEPA tariffs and Section 301 tariffs, but they usually don’t apply to products covered by Section 232 tariffs. Some 232s, meanwhile, apply to both a covered product (e.g., steel) and a product containing a covered product (e.g., washing machines), but tariffs on the latter will depend on its exact content, with 232 tariffs on the covered materials and IEEPA tariffs on the rest—unless, of course, some other exception or penalty or “trade deal” term applies. (The IEEPA fentanyl-related tariffs, for example, apply to all products from Canada and Mexico, unless they comply with the U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade agreement.)

Got it?

An August U.S. Customs and Border Protection fact sheet summarizes some of these rules but—in a classic case of laugh/cry—contains clear disclaimers about relying on it and is already very much out of date. (An update hasn’t been published.)

This summary, however, doesn’t really do justice to how crazy and variable U.S. tariffs have become for trillions of dollars’ worth of annual commerce—and how hard it is for American importers to simply figure out how much they owe the government. Consider, for example, this framework from the trade gurus at Sandler, Travis, & Rosenberg showing when executive branch tariffs “stack” and when they don’t:

When real-world tariff rules look like a sitcom take on the world’s most complicated (and boring) board game, you know you have a problem.

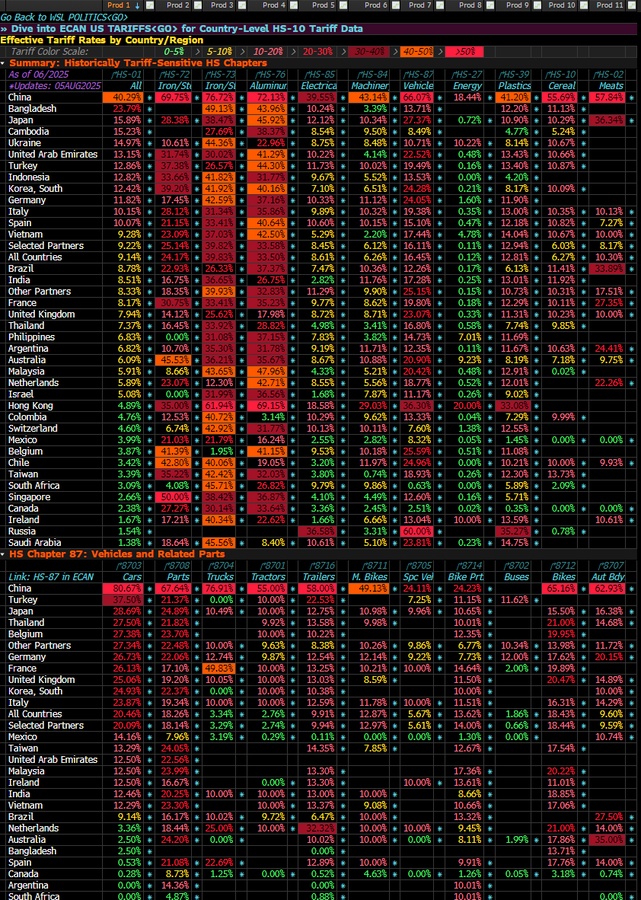

A recent Bloomberg terminal screenshot of applied tariff rates (i.e., what importers are now paying) gives us a little more flavor of the huge variation that now exists but is also just high-level averages from a few big countries. Tens of thousands of other tariff numbers lurk beneath the surface as product descriptions get more detailed, and the figures also would be different for other countries and for different supply chain configurations.

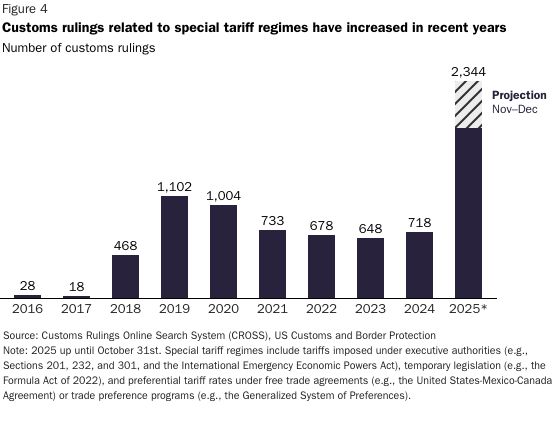

These numbers are also already out of date, which brings us to the third big complexity problem and shift from the pre-Trump era: The new tariff rules are constantly changing. Before Trump’s first term, for example, the government revised the HTSUS only a few times each year and usually for boring, technical reasons that mattered only to a handful of customs brokers and lawyers. Following Trump’s opening tariff salvos in 2018, however, significant revisions to the U.S. tariff code—both new executive branch tariffs and new exceptions to those same tariffs—became frequent and economically significant. Things died down a bit after the pandemic (which featured lots of aberrational tariff changes for obvious reasons), but the HTSUS revisions once again accelerated in 2025. In fact, the 45 tariff-related changes to the U.S. tariff code this year—34 for new tariffs and 11 for exceptions—have already eclipsed the previous, non-pandemic record set in 2019 (also because of Trump’s new tariffs):

We’ll undoubtedly see even more changes to the U.S. tariff regime in the coming months. The Trump administration has initiated other Section 232 and Section 301 investigations (a precursor to applying tariffs under these laws), and the Supreme Court challenge to the IEEPA tariffs is pending. Should the court invalidate those tariffs (fingers crossed), Trump officials have promised “Plan B” alternatives under other laws, meaning different rules and exceptions from what importers just learned this year for IEEPA. Additional import conditions (e.g., penalties for the supposed “transshipment” of Chinese goods through third countries) are still pending, and we’ll inevitably see new or changed trade deals, too.

The only certainties are more tariffs and more chaos.

A Brutal Business Environment

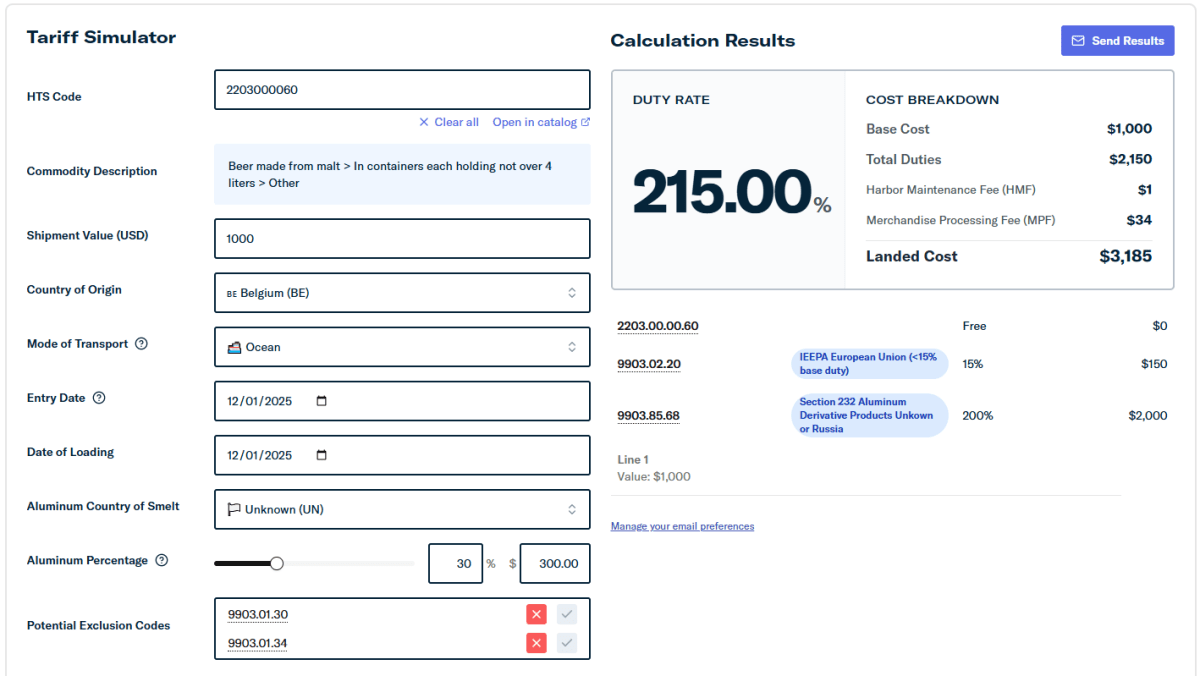

This is just the tip of the complexity iceberg, and it’s hard to express how crazy it all is in practice—even for seasoned pros. In July, for example, trade wonk Samuel Marc Lowe walked through the pain of calculating the total amount of U.S. tariffs an importer would owe on a simple can of Belgian beer, showing that what used to be a boring and easy determination (at 0 percent) now requires the American company to have detailed knowledge—and provide detailed reporting to the U.S. government—of the item’s aluminum content, that aluminum’s country of origin (not where the can was made), and whether the beer is covered by a subsequent trade deal. Adding to the absurdity, Sam actually got the calculation wrong on his first pass, and his July article was then superseded by the U.S.-EU trade deal agreed to a couple weeks later (a deal that has already changed once and may now be in further trouble). Sam also omitted a crucial detail: a U.S. beer importer’s failure to know the aluminum’s origin would default it to Russia, thereby subjecting the beer’s entire value to a 200 percent duty—a penalty presumably intended to prevent U.S. companies from feigning ignorance so they can surreptitiously import sanctioned Russian metal via beer cans and other items. (No, really.)

This handy tariff simulator from Flexport provides the absurd outcome:

Once again, this static and hypothetical snapshot is too simple for actual businesses importing stuff from abroad, as it hides the ridiculously complicated series of determinations that every U.S. importer must now make for every item he wishes to bring into the country. My Cato colleagues and I have worked for a few weeks to distill this calculus into our own flowchart, but—while I think it does a great job showing just how complicated the process has become in just a short time—even this flexible, multistep labyrinth still leaves stuff out and, again, will probably soon change in significant ways. The flowchart is so long and convoluted, in fact, that The Dispatch’s system can’t handle the image (sigh). So here’s a link.

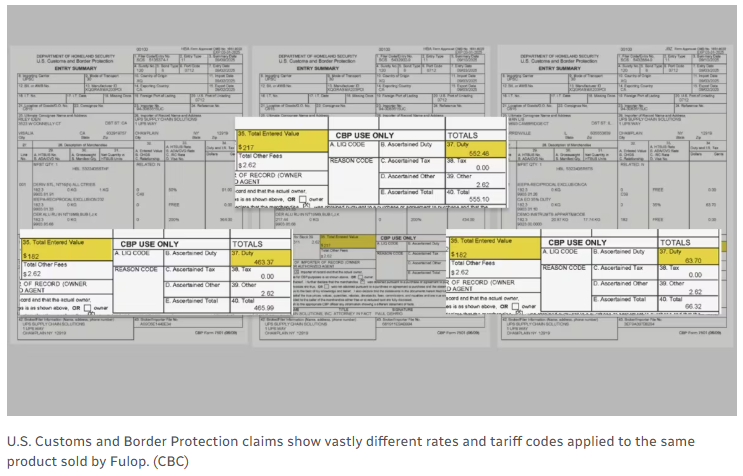

Other experts have created even more detailed versions, but these, too, are incomplete and imperfect. And even certified U.S. customs lawyers and brokers—i.e., people with direct access to proprietary and government systems and who calculate tariffs for a living—are struggling to make sense of it all. In July, for example, Bloomberg reported that these experts, their big money clients, and even CBP officials were routinely making errors in their tariff paperwork because of the new system’s unprecedented complexity, frequent changes, and lack of timely official guidance. In one particularly ridiculous case, CBP gave a Canadian firm three wildly different tariff quotes—ranging from $64 to $555—on the exact same $250 product only a few weeks apart:

All of this comes with a real economic cost, beyond the taxes and higher prices that U.S. companies are now paying. Most obviously, American firms have paid accountants, lawyers, customs brokers, and other supply chain experts to advise them on how to comply with the new U.S. tariff regime, to minimize their tariff liability, and to avoid steep penalties for getting something wrong. Many companies, for example, have hired customs lawyers to request that CBP provide official guidance on the applicable tariff rate for the companies’ products—a process that can take months and cost a small fortune. In another sign of growing tariff complexity, these requests have exploded in recent years, with now hundreds of rulings on “Chapter 99” tariffs this year alone:

Business for customs brokers is also “booming,” as U.S. companies desperately search for lawful tariff savings that they can’t find themselves and rejigger supply chains accordingly. That’s surely good news for the brokers and other middlemen, but these tariff compliance costs represent finite time and money that American companies can’t spend on core business operations. The total bill could be massive: for example, Federal Reserve economists in July of this year estimated that U.S. manufacturers would alone pay between $39 and $71 billion each year to comply with just content and reporting requirements in four Trump tariff actions:

Billions more in compliance costs are being paid by U.S. services firms (especially in retail and wholesale), and other regulatory burdens would arise from new and different U.S. tariff actions, requirements, and changes thereto.

Tariff complexity also imposes other, potentially larger costs to U.S. companies and the economy. As economist Luis Garciano noted, for example, “The growing regulatory complexity and arbitrariness of the tariff regime provides rents to those connected with power, not to innovators.” Large, well-connected incumbent firms can, say, give the president a literal gold bar to win lower tariffs, blanket exemptions, and other special treatment from the federal government. Smaller, newer players, on the other hand, are stuck with big bills. Over time, this means less dynamism and slower growth.

Uncertainty is another big economic cost. As Bloomberg reported in July, the complicated and ever-changing U.S. tariff regime has pushed many firms to postpone or scuttle major decisions on hiring, investment, purchases, and more until they have more clarity on their ultimate tax liability. For many firms, “It’s impossible to know where and when to send their next purchase orders, much less plan capital investments,” and they’re “struggling more today with understanding the rules than they are with paying the tariffs.”

Consistent with prior research on Trump 1.0 tariffs, recent surveys of the still-stagnant U.S. manufacturing sector confirm that uncertainty continues to be a major drag on domestic activity. As Bloomberg detailed in September, the burdens are particularly acute for smaller businesses that typically lack larger firms’ capital and resources (e.g., in-house compliance professionals):

The president’s ever-changing trade rules are piling up mountains of extra work for firms trying to follow them. Smaller ones in particular are struggling to cope with unprecedented requirements to trace paper trails for every widget and gadget, showing what’s in them and where they came from.

The bureaucratic burden is a less-discussed consequence of Trump’s move to hike import taxes to a hundred-year high. America Inc., which broadly cheered his election win, is already bristling at the direct cost of tariffs. Uncertainty around their on-again, off-again rollout is a drag on investment plans, too. The challenges of compliance add another layer of hurt. …

“It’s death by a thousand papercuts,” said Shannon Bryant, president of trade compliance advisory service Trade-IQ.

Adding insult to injury, these regulatory burdens now apply to many more U.S. businesses because Trump this year also dramatically curtailed the “de minimis” rule that reduced customs formalities (tariffs, paperwork, etc.) for low-value, direct shipment goods that many U.S. small businesses have used for parts and materials they need in small volumes. In the past, these businesses—say, your local auto mechanic who needs a single part from Germany—didn’t need to worry about all these rules, regulations, exceptions, and processing fees. Now, they do.

As with most new and complicated tax regimes, moreover, the tariffs have been accompanied by increased enforcement actions—further burdening (and worrying) U.S. importers:

Getting things wrong also carries the risk of civil and criminal penalties under a new enforcement push. The Departments of Justice and Homeland Security have established a joint trade fraud task force aimed at ensuring compliance with the president’s “America First” policy. Earlier this month, federal prosecutors in Newark charged UBS Gold, an Indonesian company, and three of its executives with wire fraud as part of an alleged scheme to evade tariffs on jewelry imports.

Along similar lines, there’s been a “sharp increase” in tariff-related False Claims Act litigation, in which the DOJ has alleged that some U.S. companies intentionally misclassified the nature or value of imported goods to avoid or reduce tariffs. Trade lawyers also expect more private parties to challenge tariff classifications, and CBP audits and reviews have increased substantially:

Punishment in these cases can be severe—triple damages, civil penalties, and even jail time—and thus further discourages smaller players that can’t pay a fortune to be 99 percent sure they’ve accurately navigated the new tariff bureaucracy. Put it all together, and it’s enough for at least one well-sourced observer to openly suggest that the “administration is not so much interested in reshaping trade as it is intent on sabotaging it.”

Summing It All Up

For the record, my best guess is that the administration isn’t actively trying to impose a regulatory blockade on most imports and to crush small businesses in the process. Instead, the tariffs’ seemingly impossible bureaucratic labyrinth is simply what happens when a mercurial president who just really likes tariffs is given a library of laws that let him apply and change those import taxes at any time and in whatever way he wants—and regardless of the laws’ original intent. The Supreme Court could trim those excesses in the coming weeks by invalidating the most reckless and uncertain tariffs under IEEPA, and that should be celebrated. But, given the other statutes on the books, we shouldn’t kid ourselves here: Until Congress acts to change U.S. trade law, tariffs will remain historically high, and their complexity will continue to impose a substantial, needless, and inequitable burden on the American economy.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.