As you may recall, we started out 2023 with some of my Big Questions about what the year might hold for U.S. and international economic policy. Since I like how that column aged in retrospect (see, e.g., my tepid skepticism of both a U.S. recession and China rebound in 2023), we’ll do the same this week, looking at big, open questions for this year—questions that, instead of playing pundit and confidently predicting an outcome, I’ll gladly admit relative ignorance as to how they’ll turn out. (Yes, I know, this is why I’ll never make it in politics.)

So let’s get to it.

Soft-Landing Watch

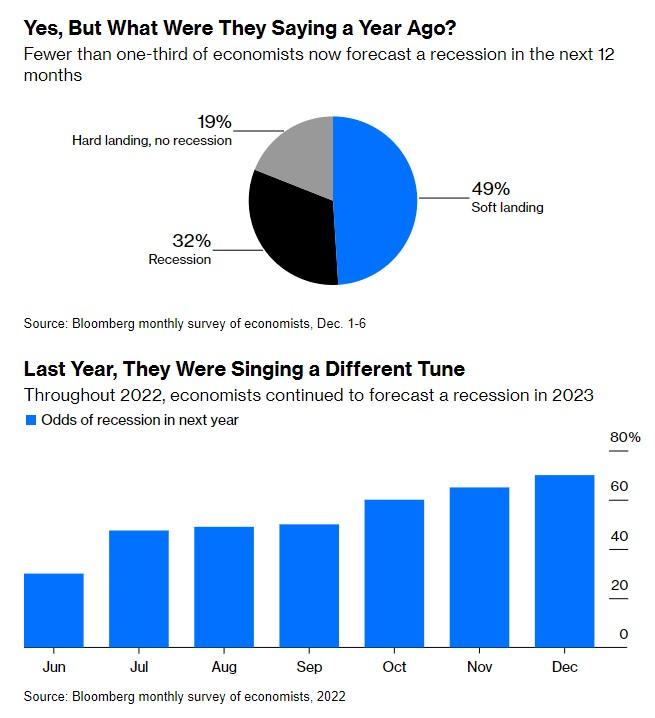

Easily the biggest economic question in the United States last year was whether we’d fall into a recession. Back then, a large majority of economists surveyed by Bloomberg, the Wall Street Journal, and other reputable sources saw a near-term recession as more likely than not, but a vocal minority predicted the much-fantasized, rarely achieved “soft landing,” whereby the Federal Reserve would tighten U.S. monetary policy just enough to cool labor demand and other economic activity without the whole thing tipping into contraction.

After a string of upside surprises and no wobbles in various recession indicators—especially in the surprisingly strong labor market—professional sentiment shifted dramatically. By December, most economists were optimistic that inflation was (mostly) under control, that the United States would avoid a full-on recession altogether, and that the Fed would aggressively cut interest rates this year (signaling that the worst of inflation is over and fueling economic growth):

Wonks will continue to debate why, exactly, we avoided a hard landing (the interminable fight between Team Transitory and Team Persistent over inflation’s causes and future direction), and it’s certainly worth considering what last year’s big miss says about the economic forecasting profession. (My take: Predictions are hard, especially coming out of a black-swan global pandemic.) But what really isn’t up for debate today is that experts think the U.S. economic outlook is better today than it was at this time last year.

This doesn't mean, however, that we’re out of the woods entirely. The Fed and most economists might think things look good, but others aren’t nearly as sanguine. This most notably includes corporate CEOs, 72 percent of whom told the business research organization the Conference Board last quarter that they were still planning for a recession in the next 12 to 18 months:

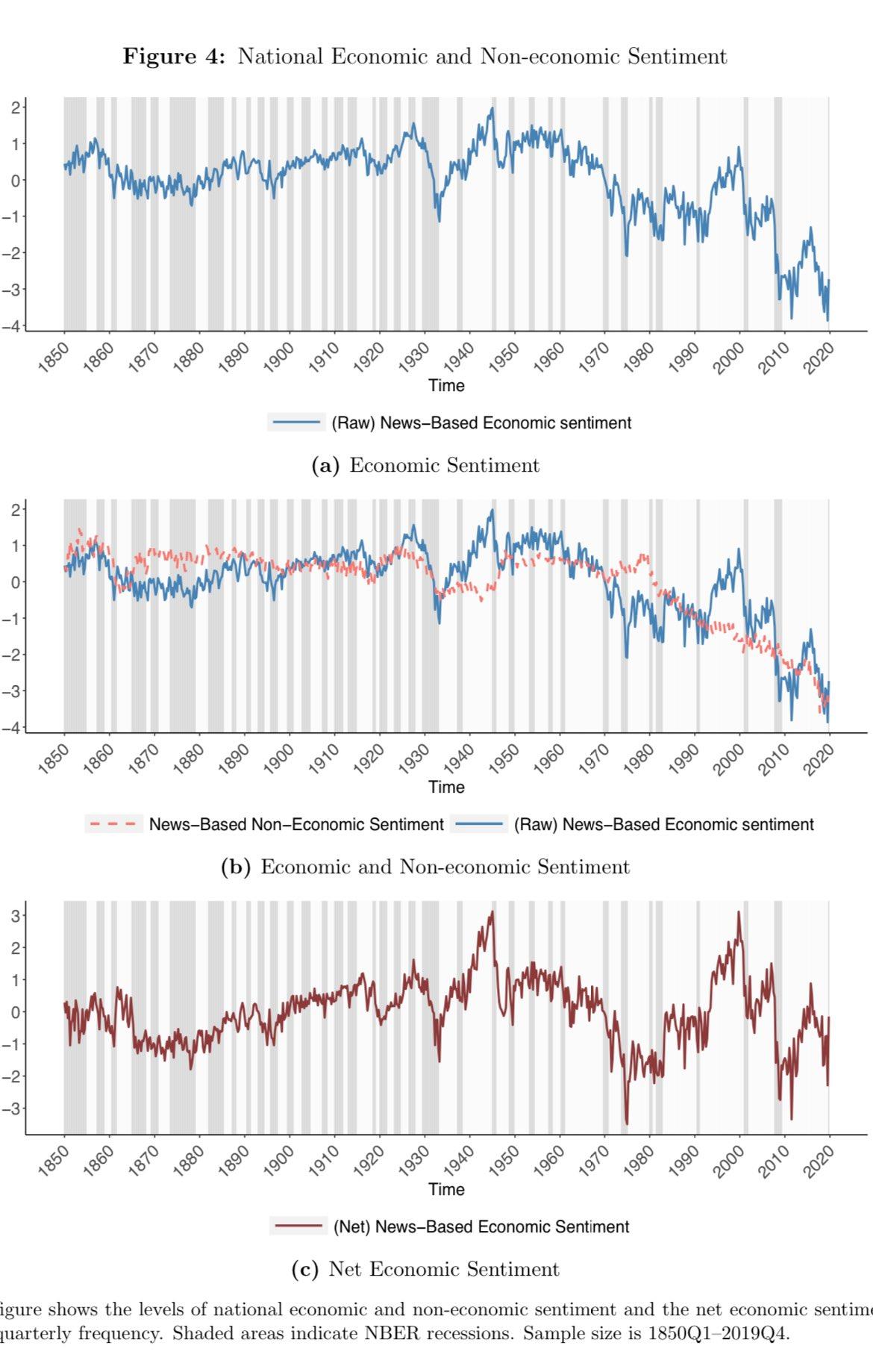

Meanwhile, American consumers continue to spend, but they remain pretty sour on the state of the economy for the same reasons—inflation, higher interest rates, etc.—that we discussed in October. This “vibescession” may be ending, in line with research showing that consumer sentiment lags inflation by several months, but it’s not done quite yet. (For those interested in the relationship between consumer sentiment and U.S. economic performance, check out this fascinating new paper.)

Finally, the U.S. labor market—and thus, the U.S. economy—might not be as strong as it first appears. For one thing, the big driver of job growth in 2023 was “acyclical” industries that aren’t reflective of the broader economy:

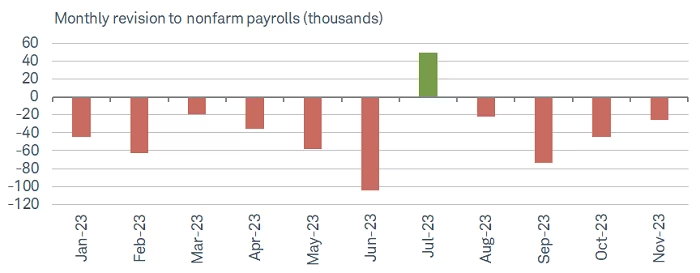

Many labor economists also are concerned that job openings data, which remain elevated versus pre-pandemic levels, aren’t accurate, and that both the string of downward revisions to the jobs figures (all but one month in 2023) and recent declines in labor force participation indicate a cooler labor market than may first appear. For you data nerds, part of the problem is the “complete disconnect” between the payroll survey (where we get the topline jobs number) and the household survey (unemployment rate and participation). The latter is looking much more pessimistic than the former:

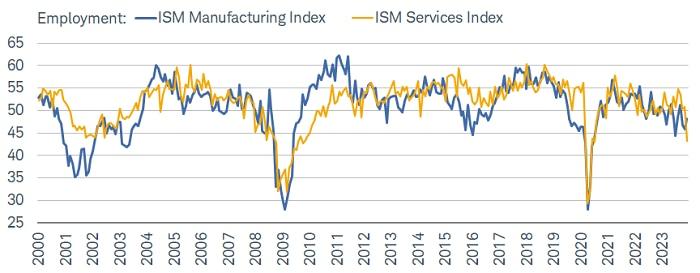

Other data give more reasons for pause: The Institute for Supply Management surveys of services and manufacturing managers have gotten much more pessimistic (see below); workers are quitting much less often (typically what happens as recessions approach); and employers are hiring less, too.

None of this means that a big crash or even a mild recession is imminent (and I still tend to side with the Soft Landing Crowd), but it does mean that we should probably hold off on turning Jay Powell’s birthday into a national holiday—at least just yet.

What Will Happen to Commercial Real Estate and the Banks Supporting It?

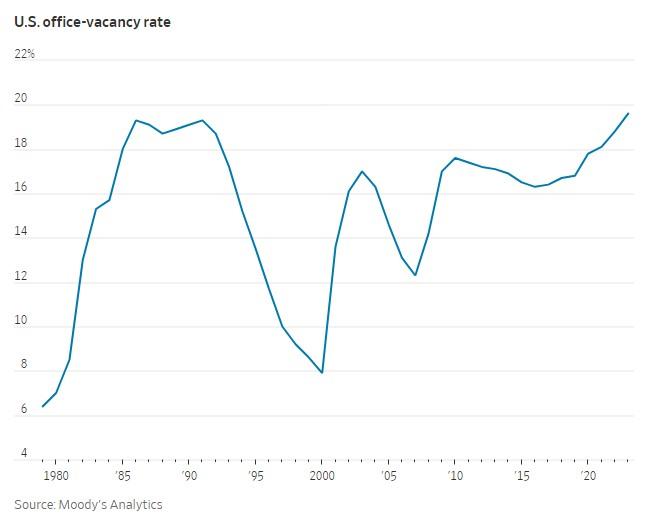

Another reason to pause the soft-landing parade is also another big thing I’m watching closely in 2024: the commercial real estate market. As the Wall Street Journal just reported, in fact, almost 20 percent of major metro office space was vacant at the end of 2023—a new record dating back to the late 1970s:

Much of this is, as we’ve discussed (and podcasted), driven by remote work, housing costs, and other quality-of-life issues. Yet contrary to what you might think, the hardest hit commercial real estate markets today aren’t in expensive coastal metros like San Francisco, D.C., or New York (which have certainly struggled, too). They’re mainly in the South (“the three major U.S. cities with the country’s highest office-vacancy rates are Houston, Dallas and Austin, Texas”) where the aforementioned post-pandemic issues fuel fires already burning from earlier decades of commercial overbuilding and where they make a big turnaround less likely. As one real estate pro explained, “The bulk of the vacant space are buildings that were built in the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s and ’80s”—and good luck getting that space rented in today’s still-strong remote work environment.

Converting these properties to much-needed residential housing could help with this problem (especially since older properties are typically easier to convert), and conversions are popping up around the country. But not all properties can be converted, and the ones that can likely need two big things: 1) buy-in from local regulators and voters (to revise building codes, zoning rules, and other regulations—see this new paper for a glimpse at the regulatory burden commercial properties face); and 2) a big haircut from current owners to make the conversion numbers work without massive government subsidies. Here’s one recent example of types of price cuts that may be needed:

This haircut is where the recession linkage may come in. While the U.S. commercial real estate market alone (probably) isn’t big enough to start a recession, a new paper provides an eye-opening look at how current commercial weakness could infect the U.S. banking sector (emphasis mine):

Using loan-level data we find that after recent declines in property values following higher interest rates and adoption of hybrid working patterns about 14% of all loans and 44% of office loans appear to be in a “negative equity” where their current property values are less than the outstanding loan balances. Additionally, around one-third of all loans and the majority of office loans may encounter substantial cash flow problems and refinancing challenges. A 10% (20%) default rate on CRE loans—a range close to what one saw in the Great Recession on the lower end—would result in about $80 ($160) billion of additional bank losses. If CRE loan distress would manifest itself early in 2022 when interest rates were low, not a single bank would fail, even under our most pessimistic scenario. However, after more than $2 trillion decline in banks’ asset values following the monetary tightening of 2022, additional 231 (482) banks with aggregate assets of $1 trillion ($1.4 trillion) would have their marked to market value of assets below the face value of all their non-equity liabilities. To assess the risk of solvency bank runs induced by higher rates and credit losses, we expand the Uninsured Depositors Run Risk (UDRR) financial stability measure developed by Jiang et al. (2023) where we incorporate the impact of credit losses into the market-to-market asset calculation, along with the effects of higher interest rates. Our analysis, reflecting market conditions up to 2023:Q3, reveals that CRE distress can induce anywhere from dozens to over 300 mainly smaller regional banks joining the ranks of banks at risk of solvency runs.

Numerous media reports show pressures at regional banks with substantial exposure to the commercial real estate market, and bigger banks face similar (albeit smaller) risks: “Commercial property, and in particular mortgages on less-full office buildings, had been one of the biggest factors pushing up problem debts.” As the New York Times reported earlier this year, moreover, “In its annual report released last week, the Financial Stability Oversight Council — a watchdog created in the wake of the 2008 banking crisis — called commercial real estate the biggest financial risk to the economy.” How this all shakes out could go a long way to determining, deservedly or not, whether future Jay Powell Days are happy or somber occasions.

Is 2024 the Year American Manufacturing Is Actually Great Again?

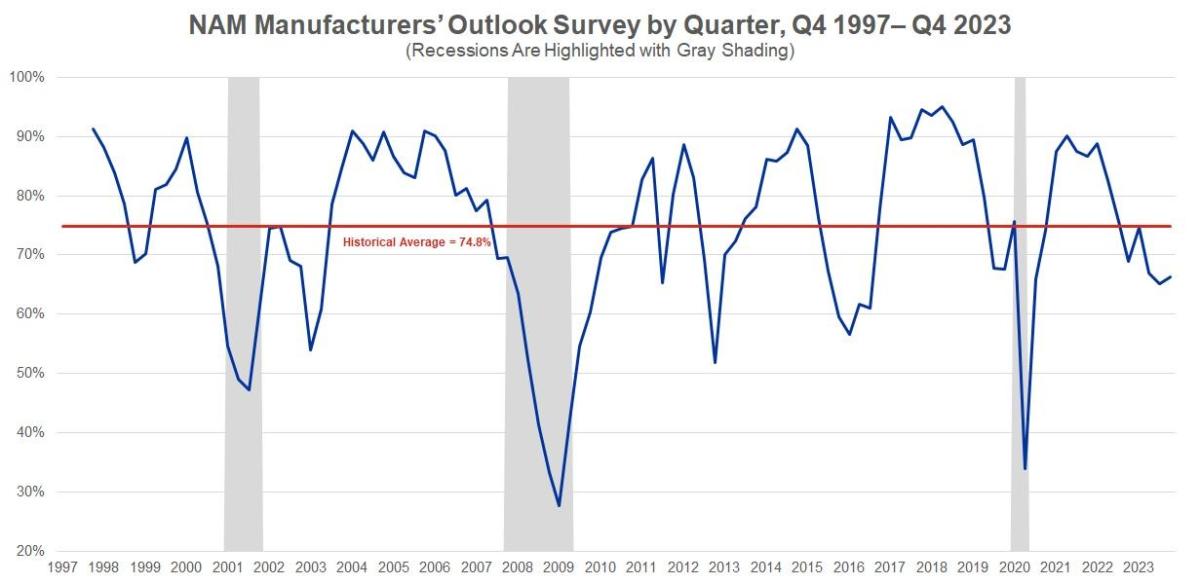

Last year was a bit of a weird one for U.S. manufacturing and industrial policy. On the one hand, there was a big and undeniable increase in manufacturing-related construction across the country—a stat the Biden administration and literally every Democratic partisan and industrial policy fan on the planet (I assume) cited constantly to show that Biden had truly, finally made American manufacturing great again. Meanwhile, the actual U.S. manufacturing sector—i.e., the one actually producing stuff and hiring actual manufacturing (not construction) workers—struggled all year, thanks to higher interest rates, continued materials inflation, worker shortages, economic uncertainty, tariffs and trade disputes, and other headwinds. For example, the ISM’s private survey of manufacturing purchasing managers (aka the “PMI”) just recorded its 14th straight month in contraction territory; the entire U.S. manufacturing sector added a mere 12,000 jobs for all of 2023 (assuming December isn’t also revised downward); output and productivity are stagnant; and sentiment in the industry—especially for small and midsize firms—was below the historical average:

We’ve thus been experiencing a sort of “two-tier” industrial economy. In Tier One, you have big companies in industries preferred by the government (semiconductors, EVs, batteries, other renewables) and, to a lesser extent, reshoring operations because of pandemic-related uncertainties. They’re investing, more optimistic, and, theoretically at least, poised to grow in 2024 and beyond. In Tier Two, however, you have existing U.S. manufacturers, especially smaller ones and ones not targeted for government support, that are weaker and more pessimistic.

As readers of this newsletter surely know, I’m skeptical that the trillions of U.S. industrial policy dollars and related private investment will be worth the cost (i.e., that they’ll generate thriving industries and broader economic growth, not just a few random successes or obviously unrelated coincidences), and there are some clouds already on the horizon—delayed or canceled projects, grumbling politicians, unspent subsidies, regulatory obstacles, trade disputes, etc. (You were warned.) Textbook criticisms of targeted subsidies and tariffs, moreover, have long cautioned that—especially absent major supply-side liberalization—these policies won’t actually expand the economic pie but instead simply redistribute existing resources (money, materials, manpower, etc.) at a net loss for the overall economy.

But it’s far too soon to boldly conclude this is all a bust: Federal funds will keep flowing to Tier One firms this year, and some rate cuts and stronger growth might cure much of what ails the Tier Two guys. (It certainly won’t be better trade or immigration policy!) So, maybe the sector rebounds in 2024.

Regardless, you can rest assured I’ll be here to cover it.

Speaking of fizzling rebounds …

What’s Next for China?

Since we just discussed China at length a few weeks ago, I won’t belabor the issue too much today, but the future of the world’s second-largest economy is still important and uncertain for 2024. Since we last reviewed this in early December, things in China remain a mess, with problem signs almost everywhere you look, including in the military:

Economic weakness in China not only means weakness abroad (e.g., for exporters and investors) but also increased geopolitical uncertainty, as Chinese President Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party could—theoretically, at least—try to deflect local attention on widespread domestic problems by starting various overseas shenanigans. (Though fortunately, all the “Taiwan invasion” stuff had cooled way down even before the latest military corruption scandals emerged.)

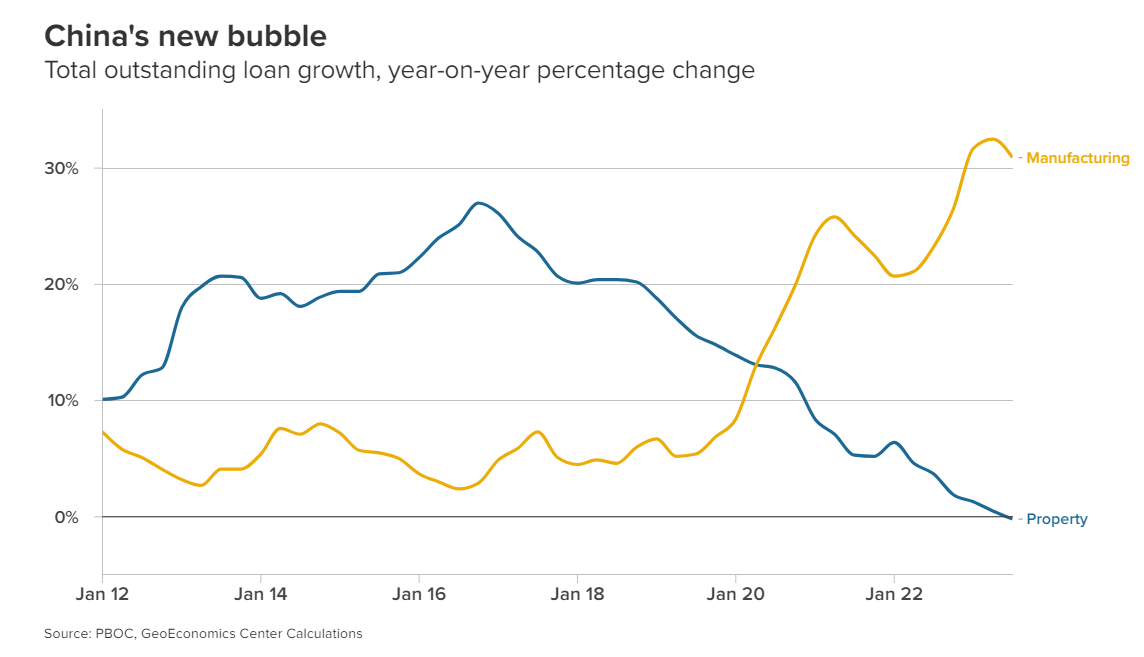

Instead of reversing course and reembracing markets, moreover, Xi is reportedly doubling down on the Marxism and industrial policy (but I repeat myself! LOL). Both carry big risks: The former could further depress the Chinese citizenry, foreign investors, and the economy more broadly; the latter can’t fully offset domestic real estate, consumption, and other economic problems, but it can ignite even more trade conflicts as subsidized overcapacity reaches foreign markets and angers local politicians, many of whom are running for reelection in 2024.

As usual, I must caution that this doesn’t mean China or the CCP will collapse anytime soon, and there are even some tepid signs that the economy may have hit bottom. Regardless, it’s a wildly important and uncertain situation amplified by the U.S. elections, and thus makes for must-see-TV throughout 2024.

Will This Be AI’s Earthquake Year?

This time last year, everyone was freaking out—in good ways and bad—about ChatGPT and other “artificial intelligence” products that were acing human tests, making cool “original” art, and writing (superficially) impressive prose in response to simple language “prompts.” As we discussed in February, numerous reports warned that these products would quickly usher in an era of mass joblessness and other sci-fi dystopias. In March, Elon Musk and another 1,000 or so “tech leaders” were so rattled by AI that they openly called for a six-month moratorium on the most advanced systems, warning that they present “profound risks to society and humanity.”

Then … nothing happened.

Ok, fine, not nothing: Last year, the technology continued to improve at a rapid clip, was increasingly adopted by U.S. businesses, catalyzed some amazing scientific breakthroughs, and certainly destroyed some American jobs (including fashion models!). However, the public-facing tech still has some problems—see, for example, this recent analysis from Stanford economist Joy Buchanan and colleagues about GPT-4’s continued “hallucinations” (e.g., fake citations) or this new image showing how AI image creators still suffer from basic spelling problems. AI is also (predictably) helping to support U.S. companies and jobs, not just destroy them, because humans are quickly adapting to incorporate the technology into their routines or to adjust their work to do things AI still can’t do well. And, of course, there are the not-insignificant facts that unemployment in the United States remains well below historical averages, and that—now almost four months since the AI moratorium would’ve ended—the techno-apocalypse is nowhere in sight.

AI technology thus appears to be following the same general trajectory as the earth-shattering ones before it—gradual, uneven advancement causing real-but-manageable disruptions thanks to good ol’ human ingenuity and adaptation. Will 2024 be any different?

What Will Happen in Argentina?

Finally, there’s Argentina and the aftermath of this fall’s shock presidential election victory of brash libertarian(ish) economist Javier Milei.

When Milei first started gaining steam, I was of two minds. On one hand, Argentina’s economy has long been a statist disaster, and Milei was saying lots of good free-market things about how to turn things around. On the other hand, the guy was … umm … quirky and saying lots other things that would give even an open-minded libertarian like me serious pause. His election was, as my Cato colleague Ian Vasquez said at the time, itself a remarkable accomplishment— “articulating a clear, liberal alternative to Peronism with popular support and electoral success”—but governing was another story. Beyond his personality quirks, Milei was a political neophyte inheriting an economy in crisis and a divided government full of bureaucratic enemies. He’ll have his every move scrutinized by skeptical media hoping to confirm anti-libertarian biases. And, as such, there remain plenty of reasons to worry that the “libertarian government” in Argentina will—fairly or not—become a cautionary tale instead of a vindicating success.

However, there’s a lot Milei can do without Argentina’s legislature, and his early speeches, appointments and free-market policy moves—aka “economic shock therapy”—have been mostly well-received by financial markets and wonks (not just libertarians!) alike. Just this week scholars with the center-left Peterson Institute called Milei’s early moves—devaluing the currency, cutting spending and regulation, lifting price controls, slashing civil service jobs, privatizing state-owned enterprises, liberalizing trade, and weakening unions—and his future plans “full of economic and political risks” but seemingly offering “the maximum chances of success given the constraints he faces.”

But, boy, are there big constraints and risks remaining. Beyond the economy’s legacy problems and the inevitable (promised) pain that reforms will inflict, strong resistance to Milei’s agenda has unsurprisingly materialized. A court last week, for example, suspended his sweeping labor reforms after the country’s biggest union challenged it (Milei’s team will appeal), and protests have erupted in Buenos Aires. Many of his plans, especially dollarization, remain unfinished and/or dependent on legislative support. There’s still a very long road to hoe.

Still, what’s emerged so far is undeniably positive and unlike the chainsaw-wielding “Trump-like” caricature of Milei we Westerners saw in the media before Argentina’s presidential election. (Some of that caricature was undoubtedly intentional by Milei, if only to attract attention.) I challenge you to watch this video from the indispensable Milei Explains account on Twitter and not be blown away by both the discussion (substance and delivery) and the idea that this guy is anything (hair-notwithstanding) like Donald J. Trump:

I honestly have no idea how Milei’s time running Argentina will turn out. Parts of his agenda and persona still give me pause. But it’s not an understatement to say that his policy work in Argentina this year will be some of the most relevant—for better or worse—reforms undertaken anywhere in the world. Fingers crossed.

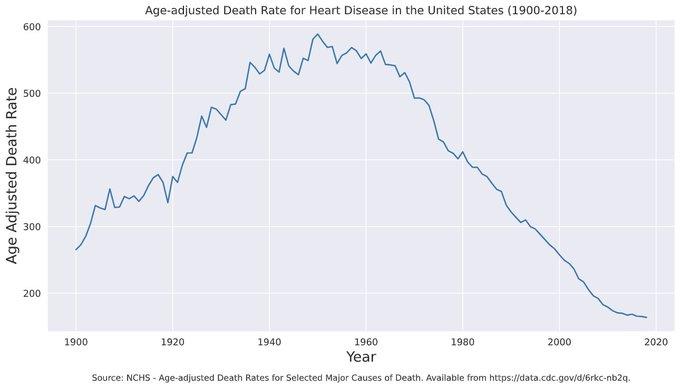

Chart of the Week

Hmm:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.