As honchos from around the world meet in Dubai for the 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) this week, it’s become increasingly clear that the much-ballyhooed “green transition” in the United States—fueled at least in part by big subsidies—has hit an equally big speed bump. “A year after President Joe Biden’s landmark climate law promised billions of dollars for America’s switch to clean energy,” Bloomberg reported last week, “some of the nation’s most ambitious renewable power projects have been shelved, electric car sales are missing targets and investors are fleeing the sector in droves.” Clean energy stocks that many thought the Inflation Reduction Act would boost have instead seen a “$30 billion collapse in the last six months,” and many analysts are significantly downgrading their emission reduction projections. As one energy consultant put it, “the euphoria has worn off and we’re starting to realize it’s still not going to be easy,” because—as another noted in the same piece—“economic realities” have set in.

While much of the clean energy sector in the United States is hurting, probably the biggest pains are being felt in offshore wind. Projects are getting delayed or canceled, companies are under serious financial pressure, lawsuits are blossoming, prices are increasing, and climate ambitions are doing just the opposite. Big Wind isn’t dead, but it’s definitely been taken down a notch or three.

In some ways, these and related problems are just your typical pandemic-era problems and nascent industry growing pains. In many other ways, however, the problems facing offshore wind in the United States have been caused or exacerbated by government policies—serving as yet another reminder of what happens when industrial policy dreams meet not economic realities, but government ones.

You can’t say you weren’t warned.

The Wind-Up

The problems facing the U.S. offshore wind industry are today well-known, but here’s a quick recap: Once projected by the Biden administration and various climate optimists to provide by 2030 a whopping 30 gigawatts of capacity (supposedly enough to power more than 10 million homes), analysts today call such targets “impossible” (or, if you prefer, a “pipe dream”). Already- or soon-to-be completed capacity would get the United States to a mere 1.5 gigawatts, and it’s “unclear” when other projects might come online. Many—including some that were already started—have been totally scrapped, at great expense (time, money, materials, etc.) to the parties involved. The most widely reported problems are with Danish wind firm Orsted, which scrapped two big offshore wind projects in New Jersey and will write off as much as $5.6 billion in investment losses when all’s said and done.

But Orsted is not alone. “In total,” the Associated Press reported a month ago, “the cancellations equate to nearly one-fifth of President Joe Biden’s goal of 30 gigawatts of offshore wind power by 2030.” And things have gotten worse since then, especially for Orsted, which is now facing a $300 million lawsuit brought by the state of New Jersey, as well as problems in New York and New England. More project cancellations might be on the way.

Some of the problems with Orsted, the U.S. offshore wind market more broadly, and other clean energy markets too are truly economic in nature. Many developers signed big contracts with state governments and utilities when interest rates were low and inflation hadn’t caused, well, everything to get more expensive. Now with actual financing, labor, and materials costing much more than the developers’ initial projections, some of those contracts don’t pencil out—a problem affecting far more than just offshore wind. Now, the price of energy produced by offshore wind projects has, even with massive subsidies, increased by almost 50 percent since 2021.

Other offshore wind problems, meanwhile, aren’t limited to the United States: Some non-U.S. projects have also been canceled, and certain setbacks (e.g., at GE, Germany’s Siemens, or Denmark’s Vestas) are company-specific and affect all of their work, regardless of where it’s located.

However (and you just knew this was coming), there are also a lot of U.S. government policies making things worse for offshore wind in the United States—and showing why so much industrial policy that looks good on paper ends up looking far worse when the shovels hit the dirt.

The Jones Act (Of Course)

Unlike some of the other things we’ll discuss today, the Jones Act is an impediment unique to U.S. offshore wind efforts. The century-old law (as we’ve repeatedly discussed), restricts shipping between two U.S. points to vessels that are American-built, -owned, and -crewed. Because an offshore wind development site in U.S. waters counts as one of those points—something Jones Act fanbois got Congress to confirm back in 2020—the law applies to all waterborne transport of people and goods (wind turbine blades, nacelles, towers, or even rocks) between the U.S. mainland and those construction sites. As such, the Jones Act introduces into the offshore wind supply chain the usual Jones Act problems.

For starters, there are few specialized offshore wind vessels that meet Jones Act requirements. In the case of the massive wind turbine installation vessels (WTIVs) needed to most efficiently assemble offshore wind facilities, in fact, there are none available for U.S. projects. Thus, offshore wind developers in the United States have three costly options:

- First, they can utilize a Rube Goldbergian workaround in which Jones Act-compliant “feeder barges” move stuff from the U.S. mainland to a non-Jones Act WTIV that’s floating at an installation site—a system that’s not just more expensive but also riskier and more time-consuming. At one offshore wind project, for example, a feeder barge’s mechanical problem delayed the transfer of essential components to a WTIV by two weeks.

- Second, they can operate non-Jones Act WTIVs out of a foreign port to service U.S. wind farms, but this approach also increases costs, delays, and other problems. When Dominion Energy built two wind turbines off the coast of Virginia, for example, it operated a WTIV out of Halifax, Nova Scotia—800 miles away!—instead of a nearby U.S. port to avoid violating the Jones Act. The result: A project that would have been completed in a matter of weeks in Europe ended up taking a year.

- Third, they can order their own WTIV from a U.S. shipyard to ensure it complies with the Jones Act. However, doing this can be even more expensive and time-consuming than the other options. For example, Dominion’s much-ballyhooed American-made WTIV was projected in 2020 to cost $500 million and be finished this year, but the vessel's price has since surged to $625 million with delivery now pushed to late 2024 or early 2025 (at best). That new price tag is around twice what it costs to build a $330 million South Korean WTIV and at least a year slower than the Korean version.

These additional costs can add up, and European wind power companies now openly admit they weren’t prepared for them. In fact, Orsted cited the American-made WTIV mess as a key reason why it recently pulled the plug on those New Jersey offshore wind projects. As Reason’s Eric Boehm reports, various industry analysts agree.

The Jones Act’s costs also don’t just apply to WTIVs: Smaller vessels to transfer maintenance personnel to the turbines are estimated to cost twice as much as those built abroad. Even a relatively simple vessel being built to install big rocks (which prevent erosion and support the turbines) has seen its price balloon from $197 million to $246.7 million. Thus, companies often ship the rocks in from Europe and Canada instead of using good ol’ American ones …

… and Jones Act beneficiaries troll U.S. waters looking to report suspected cost-saving scofflaws to the government:

The U.S. Maritime Administration has even offered to offset some of these high costs via low-interest loans (subsidies) to U.S. companies making Jones Act-compliant offshore wind vessels. But here too, protectionism raises problems: Among the strings attached to those loans is a requirement that any imported components used to construct the vessels (of which there are plenty, despite the Buy American mantra) comply with the Cargo Preference Act and thus be shipped to the United States on expensive U.S.-flagged ships.

It’s costly boondoggles all the way down.

Then There Are the Tariffs

Tariffs on wind turbine inputs further increases developers’ costs and delays projects’ completion. As the Department of Energy wrote last year, a hypothetical 25 percent tariff on various wind turbine components “would delay cost parity with new natural gas power plants by 3 years,” yet “tariffs on wind turbine components and raw materials and wind tower imports affect both the land-based and offshore wind supply chains” today.

Most notable in this regard are tariffs on steel, which account for a substantial chunk of a wind facility’s costs and are currently one of the main things pushing turbine prices ever-higher. As we’ve discussed, however, a web of tariffs makes steel in the United States abnormally expensive compared to almost everywhere else in the world. This includes the Trump-era tariffs—25 percent for “national security” and another 15 to 25 percent on Chinese imports—that Biden has maintained, plus hundreds (305 at last count) of special “trade remedy” duties on specific steel products from certain countries. Not all these steel products directly affect U.S. wind projects, but several of them do, including utility-scale wind towers, fabricated structural steel, steel plates for monopile foundations, and electrical and other “specialty” steels that, per DOE, have “limited domestic production.”

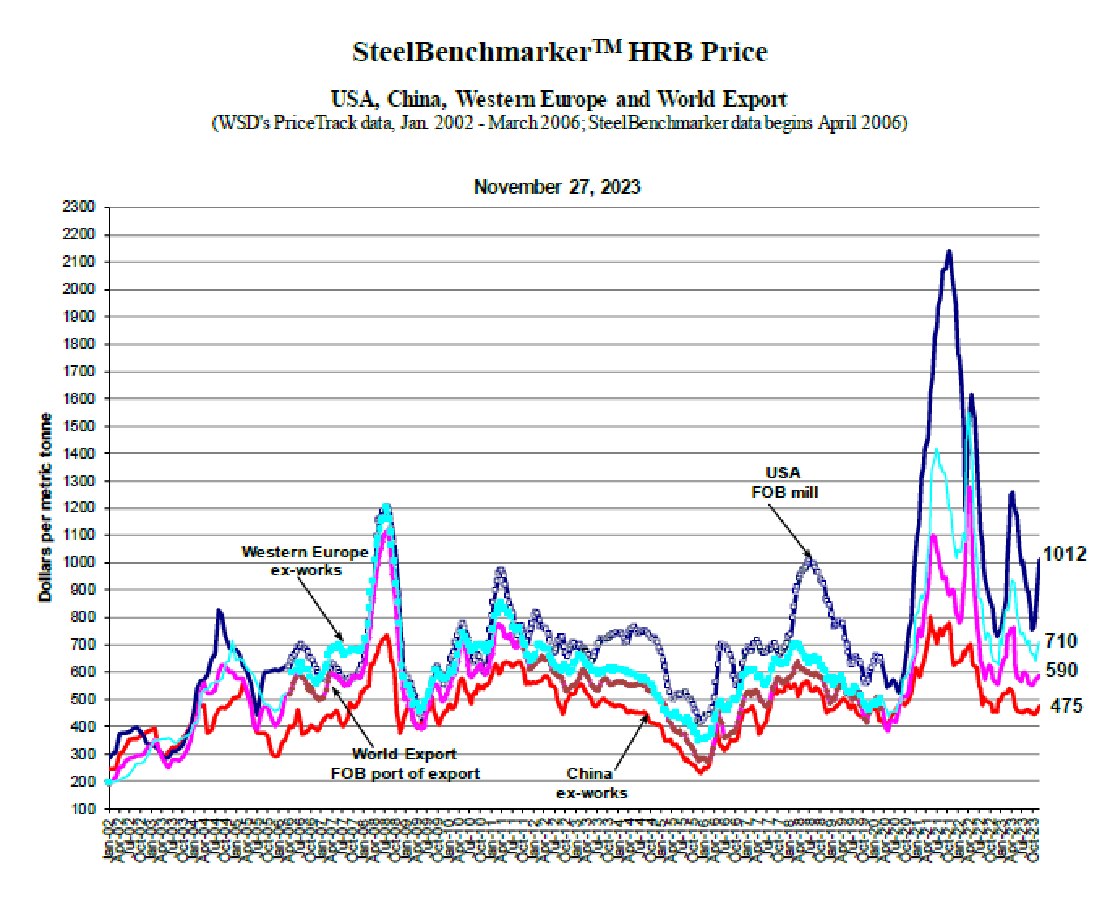

High steel commodity prices in general also can, DOE found, “affect wind turbine prices,” and tariffs on more basic raw materials will usually—as the International Trade Commission reported in a recent review of some of those wind tower duties—increase American wind equipment producers’ costs (making them clamor for tariff protection themselves). And steel prices here remain ridiculously high: The industry site SteelBenchmarker shows, for example, that hot-rolled steel prices in the United States are almost 50 percent more expensive than in Europe and around double the price in China and on the world export market:

Put it all together, and you can see why analysts were worried about tariff-inflated costs causing wind power project cancellations even before the post-pandemic bout of inflation, and why New York State in 2022 actually suspended its new Buy American mandate for an offshore wind project when it discovered that high U.S prices and limited domestic supplies of structural steel “would lead to development costs spiraling to ‘unreasonable’ levels.” Here’s an indicative table of the costs the state was looking to avoid for steel plate alone:

But it’s not just steel. The United States applies tariffs to many other things that wind projects or related equipment need. We have, for example, “national security” tariffs and trade remedy duties on aluminum extrusions, which are “increasingly found in wind power” and will probably face even greater restrictions in the months ahead because of a brand new anti-dumping investigation—“one of the largest in recent years” covering billions in annual imports from 15 different countries. We also have duties on large power transformers from Korea and have threatened duties on others, and we have a wide range of tariffs on imports from China that the Trump administration applied back in 2018.

Buy American?

New federal Buy American rules have raised other problems. As we’ve discussed, the Inflation Reduction Act offered “bonus subsidies” for using domestic materials in offshore wind projects—taxpayer funds that could theoretically offset higher costs for American-made materials. Some developers reportedly relied on these very generous subsidies when offering their initial, now problematically low, bids for offshore wind projects. There’s just one problem (aside from the blatant violation of global trade rules and extra taxpayer money): Sufficient U.S. manufacturing facilities to handle developers’ orders don’t actually exist and could —under optimistic scenarios recently modeled by DOE—take a decade or longer to come online, cost of tens of billions of extra dollars, and, even then, not achieve cost parity with European competitors.

So, the Financial Times reports, “developers cannot obtain bonus tax credits in the IRA for domestic products to offset higher costs,” and their rosy projections are now coming back to haunt them. According to the Wall Street Journal, in fact, another thing pushing Orsted to cancel several Northeast wind projects was that it “hoped bonus tax credits in the climate bill for using locally produced components would paper over financial cracks, but now says its wind farms may not qualify.” So now, of course, the company’s threatening to leave the U.S. market altogether if it doesn’t get even more subsidies.

Regardless of those shenanigans, the whole situation reveals a potential “chicken-egg” problem for those widely praised Buy American bonuses that were supposed to create a wind energy boom in the United States. Wind developers need the subsidies to make their very expensive projects pencil out but can’t get those subsidies without using local products; local producers, however, won’t invest in manufacturing that stuff without demand assurances from new wind projects … which might not happen because they can’t use local content (because it doesn’t exist). All this uncertainty is compounded by the fact that the IRA passed via “budget reconciliation” and could thus be easily overturned by simple majority vote during the long lifetime of a wind facility—something many Republicans and conservative groups are already gunning to do.

I’m exhausted just thinking about it.

Regulatory Burdens

Finally, it’s been widely reported that offshore wind projects have been hit by federal, state, and local regulations, mainly related to permitting, that further delayed projects and increased costs. A recent Atlantic Council report summarizes the main federal regulatory hurdles that wind projects face:

Since 2009, the US Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) has been responsible for lease sales and the coordination of permitting activity for US offshore wind projects. However, the US Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) remains responsible for offshore wind safety and environmental enforcement and compliance, while other agencies have environmental authority over permitting processes related to protected species and other filings under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). This lack of federal coordination can result in delays issuing Environmental Impact Statements—federal documents that assess the impact that a project might have on the surrounding environment—preventing the deployment of these projects.

Similarly, connecting offshore wind power to the onshore electricity grid remains a work in progress in the United States, and will require significant infrastructure development. The environmental impact of expanding transmission infrastructure is largely unknown and will be subject to its own regulatory process.

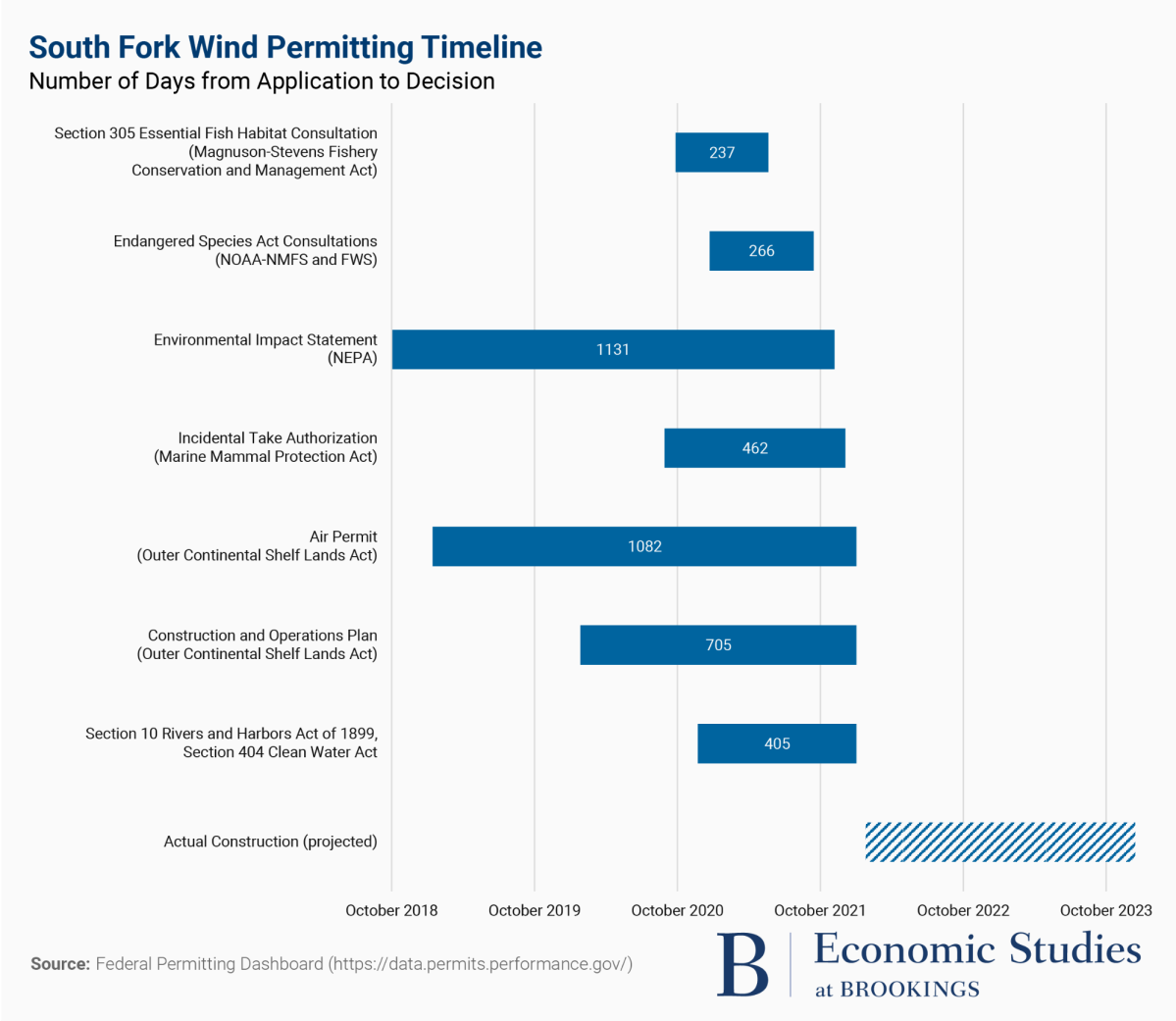

The Brookings Institution adds that offshore wind projects also often require special reviews by the EPA under the Clean Air Act and by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and must also comply with “additional marine life and bird protection requirements, which can be challenging.” They use the South Fork Wind project, which was first proposed in 2015 and is now scheduled to start producing next year, as an illustrative example of how the federal regulatory process works in practice:

That “illustrative” permitting timeline, however, might be abnormally swift at a mere three-plus years. As we’ve discussed, NEPA has long delayed federally funded projects for much longer, and the American Clean Power Association reports that NEPA reviews today take 4.5 years on average and 6.5 years for transmission projects. They can sometimes exceed a decade. The industry group adds that offshore wind projects raise particular regulatory concerns and is thus advocating for offshore-specific reforms—reforms that, along with the broader ones, remain stalled in Congress despite bipartisan support.

Meanwhile, only a few offshore wind projects have run the permitting gauntlet, while the vast majority sit in that phase or an even earlier one:

As R Street’s Devin Hartman notes, recent Biden administration regulatory reforms will help unstick things a little, but the “most critical” moves require legislative action and thus remain untouched. As a result, he laments, “clean energy continues to be a kinked regulatory hose. Subsidies merely increase the pressure. Predictably, capital markets see a ‘dislocation between policy intent and current investment,’ causing worse bottlenecks and energy market dysfunction.”

Piecemeal procedural reforms, moreover, don’t address the other big regulatory problem increasing complexity and delays: litigation by so-called “stakeholders,” which can add years to projects even after a permit has been issued. This is again happening for offshore wind (and not necessarily for well-intentioned reasons). The aforementioned South Fork Wind project, for example, has faced multiple NEPA-related lawsuits filed by coastal locals (at significant expense to the developer). In Texas, meanwhile, a conservative group has challenged the Vineyard Wind project in New England, alleging NEPA and other violations. (Ironically, the group can cite supportive legal precedent that was developed in environmentalists’ challenges to offshore oil and gas development.)

At the state and local level, meanwhile, citizen groups are using various local laws to stop offshore wind projects or the transmission lines connecting them to the mainland, or to push them much farther offshore (which means more time and money to build them). As the FT reported in September, for example, residents of several New Jersey oceanfront communities have been instrumental in helping to scuttle two Orsted offshore wind projects based on—justified or not—“fears of harm to marine life and fisheries, and ocean views marred by spinning wind turbines.” They’ve filed numerous lawsuits to challenge wind projects, have protested groundbreakings, and have convinced local governments to block permits and easements—blockades that have required costly lawsuits to get unstuck. As one mayor put it, opponents “will do whatever it takes to stop this. … If that means lawsuits, we’ll do lawsuits. If that means we literally need to form a flotilla and go out there and stop it ourselves, we’ll do that as well.”

The FT adds that the intense politicization of renewable energy in recent years—driven in no small part by Biden and other Democrats cheering the IRA at campaign events—has caused opposition to offshore wind in New Jersey to increase from 15 to 40 percent, “with the increase almost entirely among Republican voters.” Even with the Orsted projects canceled, meanwhile, the residents of Ocean City are proceeding with their lawsuits—including against the state for trying to override localities’ power over these (and other) projects.

Regardless of the merits of these challenges, they’re undoubtedly going to slow things down even further.

Summing It All Up

Not all planned U.S. offshore wind projects are in peril, of course, but many are—and government trade and regulatory policies are a big part of the problem.

Tariffs, the Jones Act, and impossible Buy American rules raise project costs far beyond what was initially assumed. Just as importantly, these and other policies can significantly delay offshore wind construction for months or even years. That, too, costs money in terms of both time and the increased risk of things going sideways for whatever reason. As the AP reported this summer, 27 U.S. offshore wind projects were contracted before financing and materials costs exploded, and “the delay between signing purchase agreements and getting final approval to build allowed unexpected cost increases to render many projects economically unfeasible.”

Some of that delay is unavoidable—these are big projects, and some amount of regulatory scrutiny is inevitable—but a lot of it is just needless bureaucracy that people of all partisan stripes want reformed. But of course the laws haven’t been reformed, so prices rise, projects get canceled, climate targets get missed, and finite resources—money from investors and taxpayers, construction materials, labor, etc.—get diverted from more productive uses and maybe even scrapped altogether. Did all those rosy offshore wind projections consider any of this? Doubtful.

In this regard, the offshore wind situation provides yet another cautionary tale about U.S. industrial policy and similar types of complicated government economic plans. Projects that might make sense on paper can make less sense—or none at all—during implementation (and after some resources have already been deployed). That change comes from political strings, pre-existing bureaucracy and policies, or newly partisan opposition that all add significant costs and time to once-neat and tidy calculations. Indeed, literally as I’m typing this I read that the $7.5 billion Congress provided for electric vehicle chargers back in 2021 has resulted in a grand total of zero units deployed today, thanks to politics, state and federal bureaucratic complications, Buy America restrictions, and “equity” concerns. As a result, EV advocates worry that “delays in installing chargers are imperiling efforts to drive up EV adoption”—delays that in turn devalue U.S. EV subsidies (and subsidized projects) too.

None of this means that wind power or EVs or other “green” products are good or bad in the long term, or that every one of these projects will fail. But it does argue for a much different approach to finding that out, one that starts with supply-side reforms to existing trade and regulatory restrictions, and then—if needed—affects demand via broad, relatively simple consumption taxes or consumer subsidies. That’s a far, far cry from what we have today, and we’re now seeing its results off the coast of New Jersey. The only remaining questions are how many more failures will follow, and how much it’ll cost us to find out.

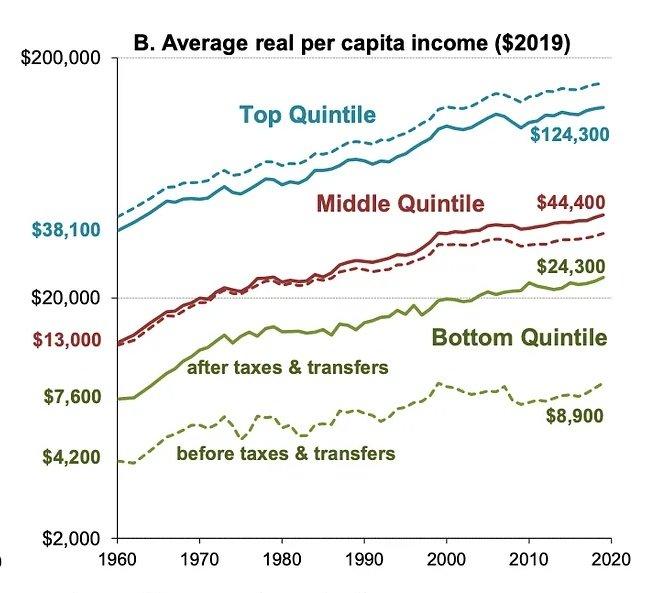

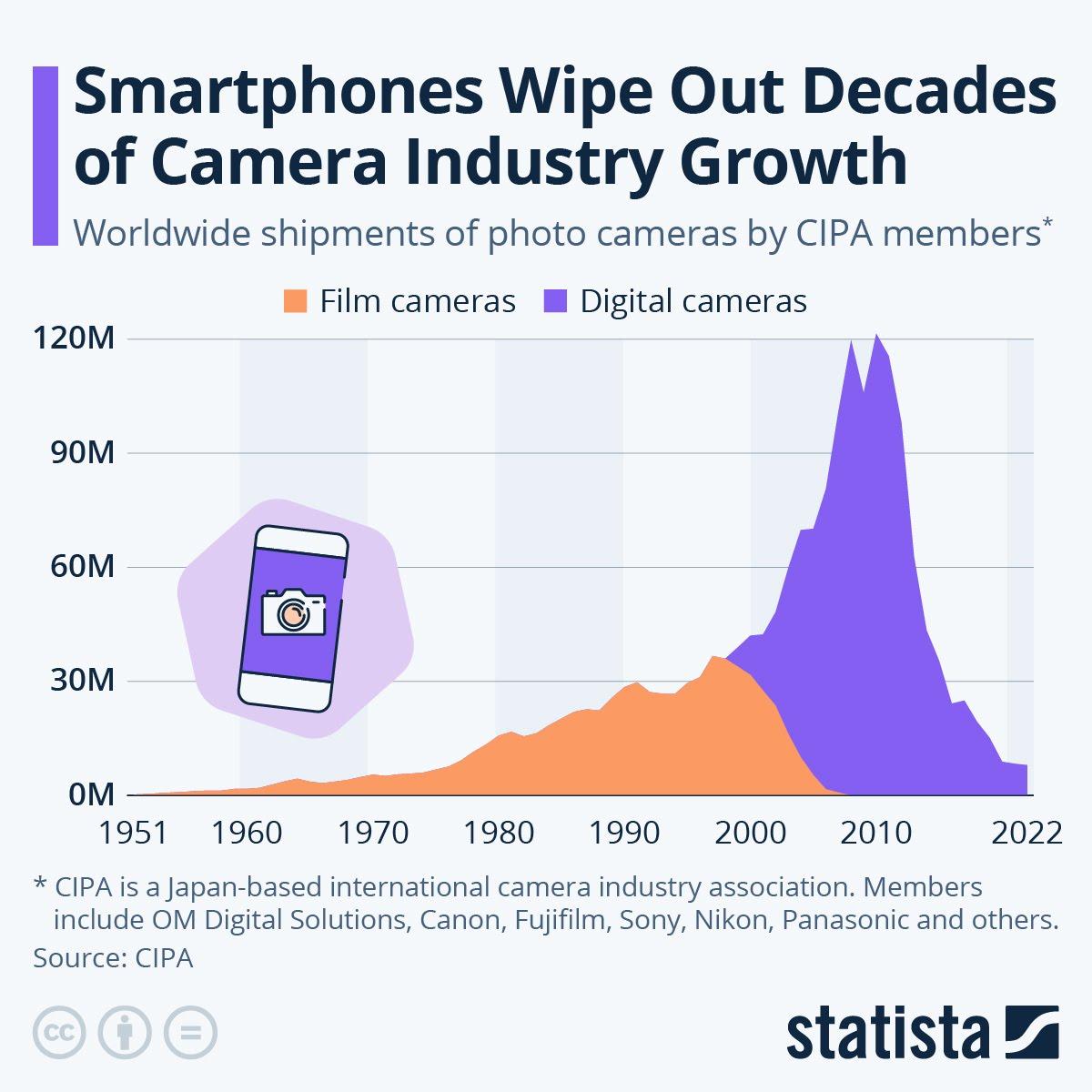

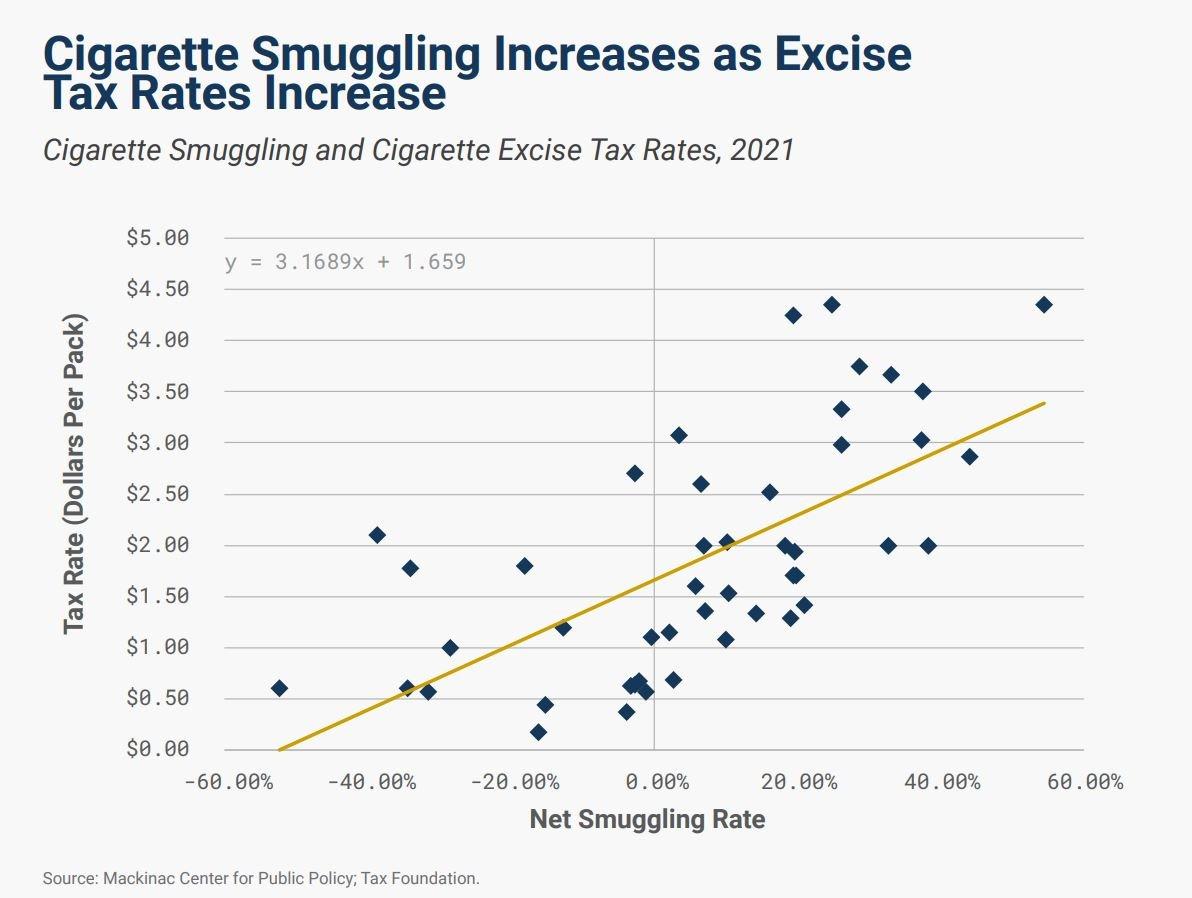

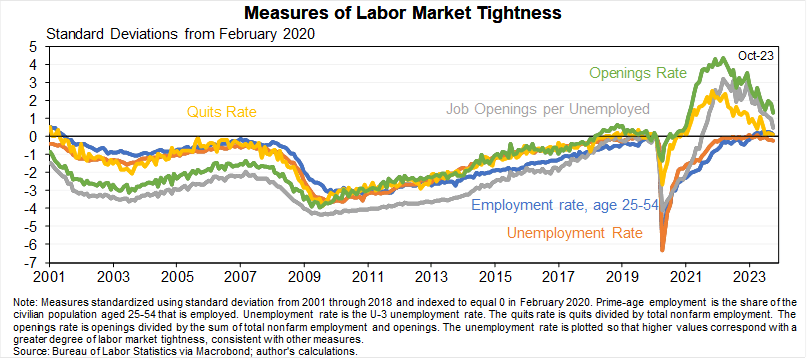

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.