Dear Capitolisters,

Weeks before this newsletter existed—you know, way back in the summer of 2020 (which honestly does feel like a million years ago)—The Dispatch Management asked me to gaze into my crystal ball and answer the question of “What Would a Biden Administration Do on Trade?” At that time, I wasn’t very optimistic about Biden on trade but did expect modest improvements over his predecessor in some—but not all—key areas. Now that we’re a year into that administration, we can make an initial assessment of both how Biden has done—and how well my predictions turned out.

(Spoiler: pretty poorly and pretty well, respectively.)

Before I begin, however, a quick note about my methodology for judging Biden’s 2021 performance: as Capitolism readers know well by now, I’m a strong supporter (understatement!) of free trade and free markets—for affirmative economic, geopolitical, and moral reasons but also because the alternative to admittedly-imperfect and messy freer market policies—protectionism—is just so much worse. In this regard, the Trump administration’s trade policies were a long and painful lesson in relearning what trade policy experts and presidents understood well by the mid-1990s after decades of U.S. managed trade messes and costly, ineffective unilateral protectionism. I won’t rehash those lessons here, but you can find plenty to chew on here (tariffs) and here (China) and here (trade generally). That said, I also understand the politics of trade—especially right now—and thus have never expected Biden (or any other president, for that matter) to suddenly become Milton Friedman or even George W. Bush in 2021 America. My grades today—much like my predictions in 2020—account for these realities, as well as Biden’s own trade-skeptical history. In short, I wasn’t expecting much.

With these things in mind, today’s look at Biden’s first year will follow the format I used in 2020: we’ll look at the trade policy places in which Biden has been better than President Tariff Man; where he’s been basically the same; where he’s actually been worse; and where some outstanding questions remain.

So let’s get to it.

Where Biden Has Been Better than Trump

Sadly, the list of Biden improvements over the Trump administration’s trade policy is even shorter than the small one I put forth in 2020—and even the relatively few wins need an asterisk. For example—

Last June the Biden administration and its EU counterparts suspended tariffs on billions of each other’s imports—tariffs approved by the World Trade Organization after decades of litigation over civil aircraft subsidies (the “Boeing-Airbus” case). This brought relief to American and European businesses and consumers, but the tariffs aren’t eliminated—they’re just suspended for five years—and there’s been no real progress on reforming the underlying subsidy programs. This is probably Biden’s biggest trade “win” (and that’s saying something).

The U.S. and EU announced a similar deal in the fall related to Trump’s “national security” tariffs on steel and aluminum, but it’s worse: instead of actually lifting the tariffs, the Biden administration replaced them with a complex and burdensome set of “tariff rate quotas” that still restrict imports and help keep U.S. metals prices high. The EU, meanwhile, merely suspended its retaliation for two years—another Sword of Damocles hanging over the bilateral trading relationship. Now, the administration is working on similar managed trade deals with Japan, the U.K., and other allies—totally ignoring the tariffs’ economic costs, dubious legal justification, and continued foreign policy irritation (“national security” tariffs on British steel? Really?!)

The Biden administration has also moved a little on its promise to “work with our allies” and ditch Trump’s constant trade antagonism, but here too the progress is limited. Talks with Europe and Japan, for example, have been initiated—separately and part of a “trilateral partnership”—on China, technology, and climate issues, yet the administration has been adamant about avoiding any sort of comprehensive trade agreement—even ones already partially or even fully negotiated when Biden was vice president—with either party. As discussed in the following sections, moreover, major bilateral irritants remain.

It’s the same story elsewhere—such as the “Indo-Pacific Economic Framework” the administration announced late last year. Thus far, it’s mostly been just a bunch of talk (diplomatic readouts about “making progress” and “working together” and stufzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz) where the only clear point is that comprehensive trade liberalization and economic engagement—the kind offering real economic and geopolitical benefits but also requiring congressional approval—is off the table. On Canada, arguably our closest ally, it’s even worse, as my colleague Inu Manak relays in an email:

The Biden administration made a terrible blunder by failing to prioritize repairing U.S. relations with its northern neighbor. We’re more than a year into the administration, and there has been no discussion of a shared border management plan to avoid the trade and social disruptions caused by ad hoc border closures. Instead, Biden has continued to threaten North American supply chains, much like his predecessor, by pushing for rules that would favor U.S. manufacturing, such as stronger Buy American rules and the “union-made” Electric Vehicle tax credit scheme. This is an open slight to one of our strongest allies.

We’ll dive into the Trumpy policy flourishes Inu mentions above in the subsequent sections. For now, probably the best thing we can say about the Biden administration’s 2021 trade policy is that the United States is now back on speaking terms with its closest allies and trading partners, has picked (but not fully consumed) some of the lowest-hanging fruit, and didn’t start any new trade fights.

And that’s just about the lowest bar ever.

Where He’s Been Trump 2.0 (So Far)

As the previous section indicates, much of Biden’s first year has been a simple continuation of his predecessor’s wrongheaded approach to U.S. trade policy. Most disappointingly (and where my muted 2020 optimism was misguided), Biden has maintained almost all of Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs, as well as the United States’ blockade of the WTO Appellate Body (basically the WTO’s “supreme court”). The latter has effectively crippled the organization’s dispute settlement system—inarguably the most effective and respected pillar of the WTO. And contrary to what some trade watchers might now say (now that Biden, not Trump, is in office), the U.S. position—singlehandedly cratering the system unless all 160-plus members agree to reforms that would advantage U.S. policy positions on things like “trade remedies” (especially anti-dumping measures)—is indefensible and a major impediment to real and needed WTO reforms. It’s also letting WTO members simply “appeal” lower-level (panel) dispute decisions “into the void” (because there’s no one to hear the appeal), freeing their subsidies or protectionism—even stuff the U.S.s itself opposes—from discipline and scrutiny.

As I and my Cato colleagues recently explained, the U.S. position at the WTO makes little substantive sense—unless it’s properly seen as a continuation of another Trump administration priority: protection of the United States’ aggressive and expansive “trade remedies” system, which has—much to the chagrin of other WTO members (and not just China)—facilitated hundreds of special tariffs on imports on increasingly dubious grounds. (More on that here and here and here.) These duties, as you may recall, are the ones applied to imports of construction materials (especially lumber), fertilizer, and intermodal chassis—even amid skyrocketing home and food prices and a massive shipping crisis. Biden and Trump don’t really deserve blame for applying the taxes—that’s the system’s fault—but they do deserve blame for stubbornly refusing to reform that system (and thereby help U.S. importers and consumers while advancing other U.S. trade and foreign policy priorities in the process).

Biden also has maintained all of the tariffs that Trump imposed on imports from China, even though his administration has repeatedly admitted that China isn’t living up to almost all of its commitments under Trump’s big “Phase One” deal, and that the tariffs—which were supposed to ensure Chinese compliance—thus aren’t working. Here’s how Bloomberg just put it:

Officials have privately admitted that Trump’s tariffs are inflicting more harm on U.S. businesses and households than on Chinese exporters. They’ve also acknowledged that the duties have lost a lot of their leverage. Data point to China having posted a record trade surplus with the U.S. in 2021, thanks in large part to Americans’ pandemic-stoked appetite for Chinese-made goods, including home electronics and bicycles. Raising the tariffs, which cover more than 60% of China’s exports to the U.S., would be a controversial call at a time when the U.S. economy is seeing its highest inflation in decades.

Bloomberg and other outlets thus acknowledge that the only thing keeping the tariffs in place these days is politics—in particular, fear of Republican and labor-union backlash. That position is questionable but not surprising. Regardless, politics don’t make the position’s logic and substance any less foolish.

The Biden administration has also vigorously defended Trump’s tariffs on metals (under “Section 232”) and Chinese imports (“Section 301”) in U.S. courts, thus signaling its comfort with Trump’s troubling expansion of executive authority over trade and the far-too-ambiguous laws delegating Congress’ constitutional powers to the president. (As you’ll recall, this was one area in my 2020 report that just wasn’t clear.)

Things aren’t much better away from tariff policy. For example, the Biden administration appears intent on utilizing the more protectionist elements of Trump’s other big trade “accomplishment”—the renegotiated NAFTA (the “U.S. Mexico Canada Agreement”). Most notably, the administration is interpreting the USMCA’s “rules of origin” for automotive goods—which dictate high levels of North American content and thus raise car prices in the United States—to make them even more protectionist, despite the objections of Canada, Mexico, and many automakers. They’re also big fans of the agreement’s intrusive mechanism to enforce the USMCA’s labor mandates (which isn’t surprising since U.S Trade Representative Katherine Tai helped write the text when she was in Congress).

Where He’s Been Worse (So Far)

As if Biden’s continuation of Trump’s trade policies wasn’t bad enough, there are at least three areas where he’s probably been even worse. Perhaps most surprisingly, Biden has expressly rejected pursuing any new free trade agreements. This moratorium thus forecloses deals started under President Obama, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership with Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia and several other countries or the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with the EU, and started under Trump, such as the U.S.-UK FTA or the U.S.-Kenya deal. The latter agreements probably aren’t too far advanced, but the Obama deals don’t benefit from that excuse. Indeed, the TPP is now in force between most of its eleven members (as the re-branded “Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership”), is considering new members like Thailand and the UK, and would go a long way towards jumpstarting the United States’ “Indo-Pacific” ambitions and counterbalancing China’s economic and geopolitical gravity in the region. The last point is especially salient today, now that China’s CPTPP alternative—the less-ambitious Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership—has entered into force with many of the same Asia-Pacific countries.

Once again, politics (or political cowardice) blocks the obvious move.

Biden has also doubled down on Buy American restrictions on federal procurement and industrial policy. Trump loved these things, too, but his team (thankfully) lacked the competence and patience to really advance the protectionist ball here. The Biden administration, by contrast, has been more focused (see, e.g., its new “Made in America” website for Buy American exemptions) and has congressional Democrats’ full assistance (sigh), thus enabling protectionist victories in the bipartisan infrastructure bill and likely others—like subsidies for semiconductors and renewable energy—in the coming months. The administration has also advanced misguided efforts to scrutinize and reorient multinational supply chains and has championed “local content” subsidies for EVs made at unionized facilities in the United States—an economically illiterate plan inconsistent with our trade agreement obligations that appears dead only because Joe Manchin doesn’t like it.

I suspect that Biden will be more successful—and thus worse—than Trump on these initiatives, which I also suspect will suffer from many of the same economic and geopolitical problems that plagued the things Trump did implement (because that’s just what protectionism does).

What We (Still) Just Don’t Know

I’m obviously down on the Biden administration’s trade policies so far, but it’s still early—especially for a president increasingly looking like a one-termer. That last part might seem strange, but presidents—including Biden’s friend and former boss President Obama—have historically leaned in on trade liberalization only after their last election is behind them and/or grand domestic legislation is off the table either because it’s been accomplished or because the opposition party has taken control of the legislature. A late 2022 shift toward less protectionism might not be the case with the trade-skeptical Biden even if Republicans retake the House this fall as expected, but there is a small glimmer of hope that—given Democratic voters’ general support for trade (even with China) and increasing congressional recognition that Trump’s policies were a costly failure—the president will be a little better after the midterms. Thus, for example, maybe Biden does fully nix some tariffs, re-engage on CPTPP, finally unblock the WTO’s Appellate Body, or otherwise embrace some modest-but-real trade liberalization moves (e.g., on environmental goods).

So far, however, it ain’t looking good.

One near-term test for Biden will be the temporary “safeguard” tariffs that the Trump administration imposed on global solar panels imports in 2018. Under the law, Biden has to decide in the next couple weeks whether to extend those tariffs—like Trump did with washing machine safeguards a year ago—or let them expire. As my Cato colleagues Jim Bacchus and Gabby Beaumont-Smith explained last week, expiry is an economic and legal no-brainer: The tariffs have raised prices (harming Biden’s own environmental objectives), haven’t significantly boosted U.S. production, and—if extended—will surely cause other countries to retaliate against U.S. exports (which they can lawfully do under WTO rules but have been holding off pending Biden’s upcoming decision). And lifting these tariffs would still leave in place other tariffs and trade remedy duties on solar panels from China and Taiwan—contra the claims from certain Senate protectionists that lifting the safeguards would empower China (sorry, “CHYNAH”). What Biden decides will further indicate whether he’s “Trump 2.0” or just trying to top off his domestic agenda (placating the aforementioned senators and others) before doing better things on trade in the future. President Obama, as you may recall (see my 2020 piece), made a similar pivot after securing Obamacare and then getting “shellacked” in the 2010 midterms. But Biden isn’t Obama; it isn’t 2011; and, if a recent Biden DOJ move to appeal a small exclusion from the safeguards is any indication, it doesn’t look good.

Summing It All Up

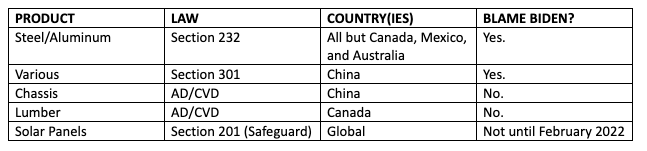

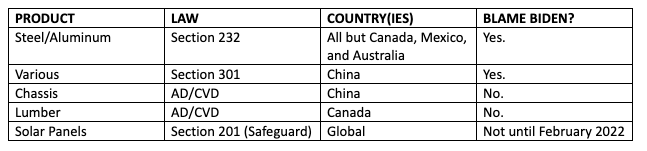

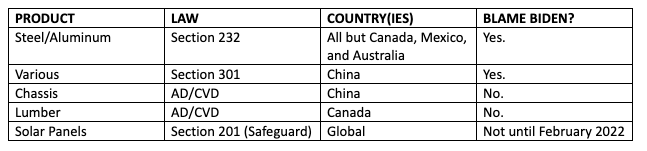

Biden has three more years to change the above assessment, but a dramatic departure from his disappointing first year seems highly unlikely given the administration’s actions and rhetoric so far. I’d thus expect more of the same in 2022 and beyond, with trade taking a backseat to domestic priorities and a gun-shy (if not outright trade-hostile) Biden administration working to quietly mitigate some of the Trump administration’s many trade mistakes without spending the political capital necessary to eliminate them outright—even for measures that, like metals and China, Biden could nix with the stroke of a pen. As noted, not every U.S. tariff action is Biden’s fault, but after a year-plus in office he does bear responsibility for several—including the ones causing the most economic and geopolitical harm. For those keeping score at home, here’s a handy cheat-sheet going forward:

No one actually paying attention to Biden’s long history, the longstanding protectionism of congressional Democrats (especially those in charge), and the Biden campaign’s clear rhetoric expected much on trade from this administration. So it’s just that much more disappointing that he couldn’t even clear our very low bar.

Chart(s) of the Week

Midwest population growth (source):

Chart (Crime) of the Week

Thankfully fixed here.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.