Dear Capitolisters,

Just a few short months ago, the entire country went crazy over eggs. Maybe it was the cold weather or holiday boredom, I dunno, but it seemed like everyone—politicians, pundits, comedians, my mom—in December and January couldn’t stop talking about abnormally high egg prices. The situation even spawned an endless series of very funny memes:

But all this egg chatter wasn’t just funny yolks (sorry), it also had a darker side. In particular, a rather large contingent of populists—mainly on the progressive left but not entirely—took to the interwebs to angrily proclaim that sky-high prices were caused primarily by sinister, profiteering corporations that had used their monopoly power (or whatever) to extort poor, powerless American consumers.

In a January letter to the Federal Trade Commission, for example, the group Farm Action, which “leads the fight against monopolistic corporate control over our food and farming system,” called the spike in egg prices “organized theft” by “large egg producers” to “extort billions of dollars from the pockets of ordinary Americans … without any legitimate business justification.” The organization’s petition was backed by Rhode Island Sen. Jack Reed. Meanwhile, former Labor Secretary Robert Reich tweeted that “Egg prices are up 60%. That’s absurd. People are paying up upwards of $6 and $7 for a dozen eggs. Why? Corporate greed.” He then made an (admittedly decent) egg joke: “When it comes to the corporate monopolization of eggs, the people shouldn’t go over easy.” Sen. Bernie Sanders used the situation to justify a “windfall profits tax” on large corporations: “Corporate greed is the producer of Egg-Land's Best, Farmhouse Eggs & Land O'Lake Eggs, increasing its profits by 65% last quarter to a record-breaking $198 million while doubling the price of eggs & reporting no positive cases of avian flu.”

That “producer” is actually Cal-Maine Foods, the nation’s largest egg company, and it was also the target of a sternly worded letter from Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Rep. Katie Porter, which basically parrots the previous points about high egg prices and corporate profits and then generalizes about “greedflation” more broadly: “This is a pattern we’ve seen too often since the COVID-19 pandemic: companies jacking up their prices to pad their own profits, putting an additional burden on American families and the economy as a whole. … American families working to put food on the table deserve to know whether the increased prices they are paying for eggs represent a legitimate response to reduced supply or out-of-control corporate greed.” Warren and Porter sent basically the same letter to the other members of the Big Egg conspiracy.

No formal investigations—from Congress or the FTC—have been opened.

What Drove Egg Prices?

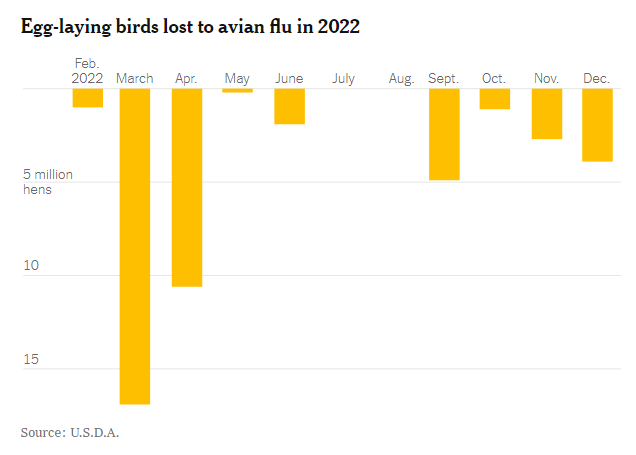

That official inaction is probably owed to the not-insignificant fact that the aforementioned complaints are total nonsense. Instead, the biggest things driving egg prices over the last 12 months have been good ol’ supply and demand. Most obviously, the United States in 2022 experienced the worst outbreak of avian influenza ever, with the virus forcing U.S. egg producers to cull around 45 million egg-laying birds last year:

As detailed in a recent piece in The Atlantic, avian flu is particularly brutal for egg-laying chickens, is really difficult to control (wild birds poop it from the sky!), and requires several months of recovery:

Everything about this current wave has aligned to put a serious dent in our egg supply. Most eggs in the United States are hatched in jam-packed industrial egg farms, where transmission is next to impossible to stop, so the go-to move when the flu is detected is to “depopulate,” the preferred industry term for killing all of the birds. Without such a brutal tactic, Bryan Richards, the emerging-disease coordinator at the U.S. Geological Survey, told me, the current wave would be much worse.

But this strategy also means fewer eggs, at least until new chicks grow into hens. That takes about six months, so there just haven’t been enough hens lately—especially for all the holiday baking people wanted to do, Thompson said. By the end of 2022, the U.S. egg inventory was 29 percent lower than it had been at the beginning of the year. The chicken supply, in contrast, is robust, because avian flu tends to affect older birds, like egg layers, Thompson said; at six to eight weeks old, the birds we eat, known as broilers, are not as susceptible. Also, she added, wild-bird migration pathways are not as concentrated in the Southeast, where most broiler production happens.

The 2022 outbreak, moreover, was particularly bad because the virus lingered for almost the entire year (as opposed to burning out quickly like it did during the last major outbreak in 2015). Throw in the usual bout of inflationary production costs—for feed, machinery, energy, etc.—and U.S. egg inventories have unsurprisingly suffered. A lot.

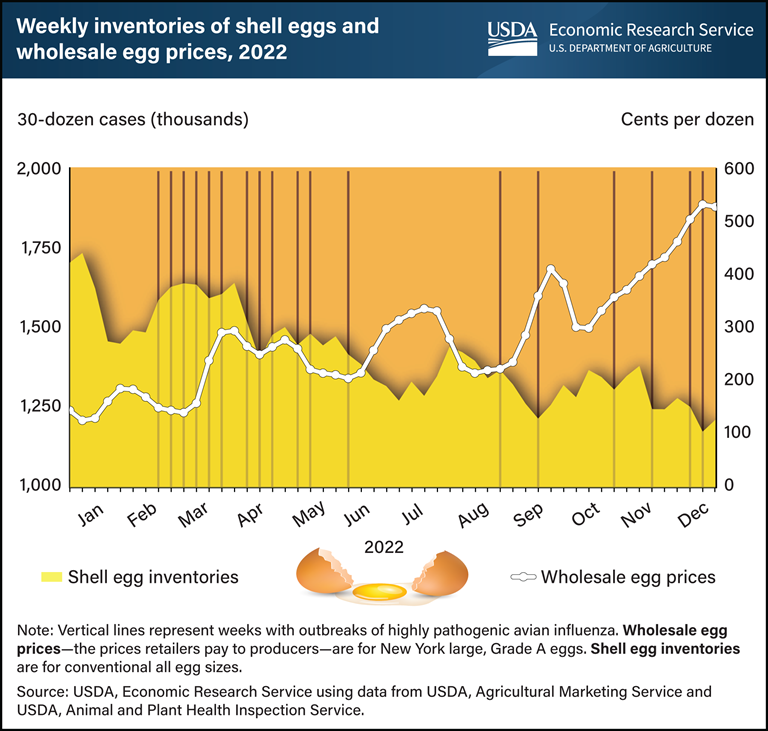

The “baking” point above next brings us to the demand side of things: U.S. egg consumption tends to peak in November and December when we’re all home doing holiday stuff, so, even in the best of supply times, egg prices tend to rise that time of year. Because demand for eggs tends to be relatively “inelastic”—high prices don’t significantly reduce consumption because there aren’t a ton of great egg (or cheap protein) alternatives—2022’s holiday demand hit 2022’s significantly reduced supply, and wholesale prices predictably skyrocketed during the holiday season:

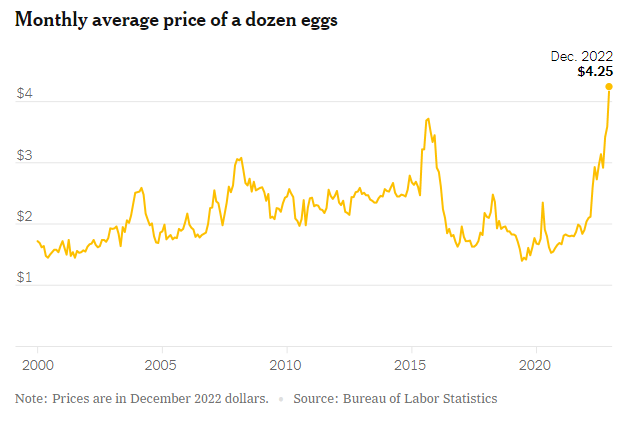

None of this should be in any way surprising. In fact, even though 2015’s bid flu was not as bad as last year’s (though it was still pretty bad), U.S. egg prices reacted in a very similar way at the end of that year:

(Kudos to the New York Times here for adjusting for overall inflation by reporting prices in 2022 dollars—something a lot of other charts didn’t do, thus making the recent price increases appear much bigger than they really are. Tsk tsk.)

But the Greedy Profiteering!

“But Scott!,” I can hear some of you yelling in the comment section, “Big Egg monopolists also reaped windfall profits last year! Surely, that’s a sign of Greedflation!!!!!”

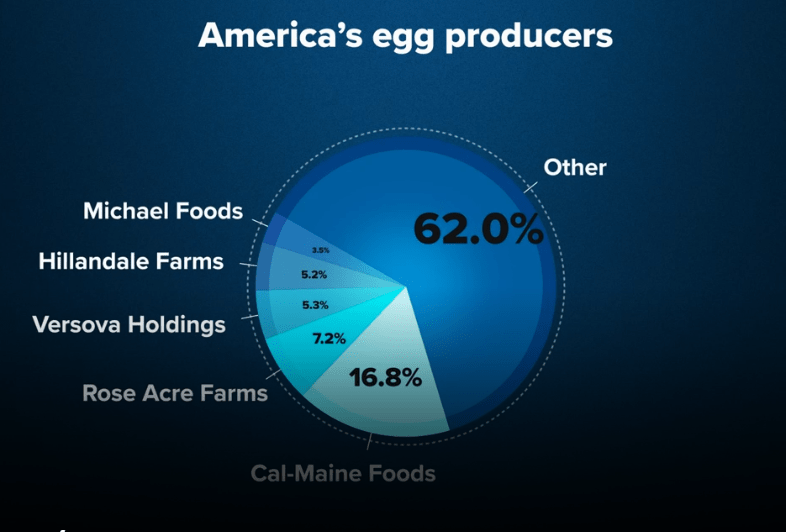

Well, yes, there are a few large U.S. egg producers, and some of them—publicly traded Cal-Maine Foods, in particular—saw abnormally high revenues and profits last year. But this is hardly proof of any Big Egg greedflation conspiracy. For starters, the U.S. egg market isn’t really very concentrated at all: Cal-Maine holds a market share of just 16.8 percent, while “[t]he second largest producer is Rose Acre Farms, with about 7% market share, followed by Versova Holdings and Hillandale Farms with just more than 5% each, and Michael Foods with 3.5%.” Overall, more than 60 percent of the U.S. egg market consists of suppliers other than Big Egg:

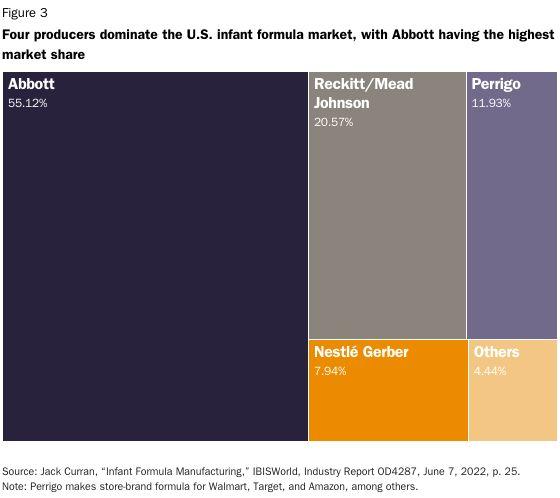

By contrast, in the infant formula market—which really is concentrated (thanks to a lot of federal policy)—just four producers accounted for more than 95 percent of the U.S. market before the crisis hit.

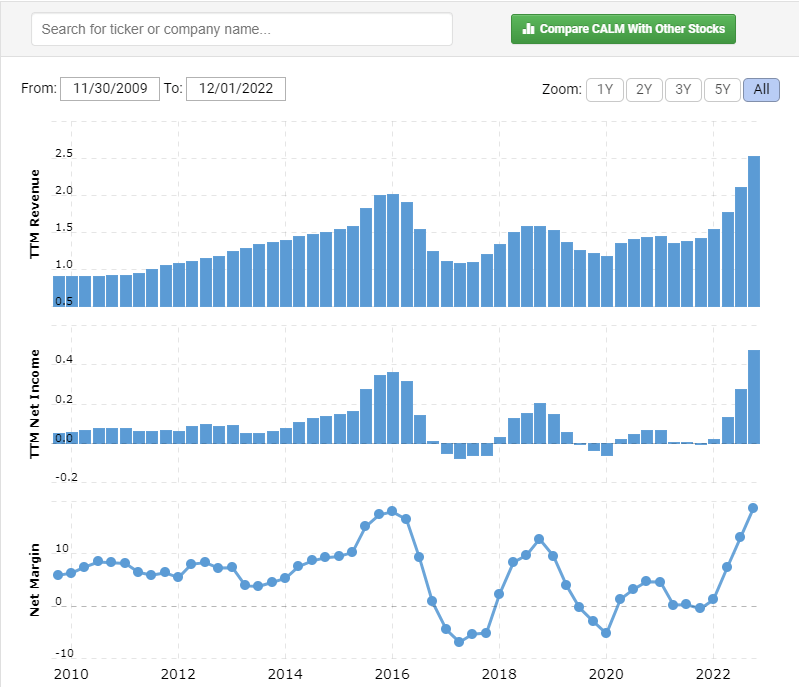

Indeed, a strong sign of the lack of concentration in the U.S. egg industry is that it’s traditionally a very low-margin industry with low overall returns—and one that, thanks to environmental, cost, regulatory, and other factors—experiences a lot of volatility, with companies frequently swinging from profits to losses and back again. Cal-Maine, for example, has actually experienced negative operating profits and negative net margins in several quarters since 2015.

Second, allegations of corporate windfall profiteering misunderstand how prices are generally determined in the U.S. egg market. As agricultural economist Jada Thompson recently explained over at The Hill, it’s egg buyers—not sellers (even big ones like Cal-Maine)—who are running the show (emphasis mine):

Commodity markets are complex—and the egg market is no exception. Egg companies are not setting prices—they are actually receiving a price that is established by someone else, in this case, an exchange that determines the market price via an auction-style method of offers and bids and an independent market reporting service.

Many eggs are traded on what’s called the “spot market.” Trading levels between egg producers and customers helps set the wholesale price. The more competition for a limited volume of eggs, the higher the price. Low demand for eggs or an excess egg supply will bring prices down. As these trades occur, the value of eggs is determined by buyer demand—and that leads to the wholesale price. …

When egg supplies are limited, e.g., flock losses related to avian influenza, but demand remains high, e.g., during the peak holiday egg buying season, wholesale prices are exacerbated. Put simply—egg producers are price takers, not price makers. Egg prices are set by the demand of those who are buying the eggs on the wholesale market.

With this essential context, Cal-Maine’s recent “windfall profits” make total sense, because, while overall egg inventories collapsed, Cal-Maine’s operations were unscathed:

“It’s a testament to the fact that they haven’t had any [bird flu] outbreaks, how good they’ve been at biosecurity in their facilities,” said Peter Galbo, a food and beverage analyst for Bank of America. “This is a very experienced, very deep management team that’s been in this industry for a long time.”

Put simply, U.S. buyers in 2022 still wanted eggs—lots of eggs—and Cal-Maine was in the best position to supply them. So, it sold at the ever-increasing prices that eager U.S. buyers were competing against each other to offer, and it thus made record revenues—a tellingly similar result, by the way, to the last time bird flu hit the United States in 2015 (see revenue and profit chart above).

Some conspiracy!

(A lot of Big Egg conspiracy theorists also misunderstand that wholesale prices—where Big Egg mainly operates—are different from retail prices, which generally involve grocery stores, not egg farmers.)

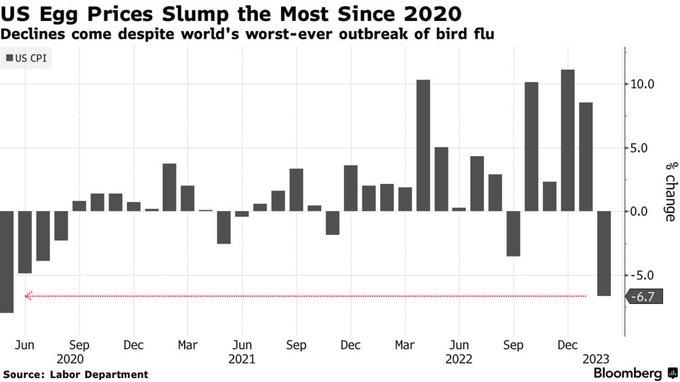

Finally, the Big Egg conspiracy has recently run into perhaps the biggest problem of all: Egg prices have declined significantly since January. In mid-February, for example, wholesale prices dropped back to levels last seen almost a year ago:

The retail figures above were two months behind the wholesale figures, but the latest consumer price index figures show February retail prices following wholesale ones:

Retail prices have declined further since then. According to the latest data from the USDA, for example, major chain grocers are now selling a dozen large eggs for as little as $2.29 here in Raleigh, North Carolina, compared to more than double that price back in December and January. At my local Walmart, a dozen large white eggs today costs just $2.32.

These prices remain above 2021 levels, but their dramatic recent decline remains fatal to the “Big Egg” conspiracy. In particular, if Cal-Maine and other major producers truly had price-setting market power, wholesale prices would have remained elevated. Instead, as numerous observers have noted, the decline in wholesale prices was a direct result of market forces—both waning holiday demand and a boost in supply—that Big Egg couldn’t control:

There haven’t been any new bird-flu outbreaks among commercial table-egg laying birds since Dec. 20, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

A prolonged period without setbacks in egg production has given suppliers a reprieve and the market time to recover, said Brian Moscogiuri, global trade strategist at Eggs Unlimited, one of the largest egg suppliers in the U.S.

And, barring some sort of calamity, retail prices will (eventually) reflect these dynamics, too.

Given the uncertainty surrounding bird flu, those prices will probably stay higher than they have been in recent years. They might even spike again if there’s another bird flu outbreak, especially since prices tend to rise in anticipation of Easter. But none of this screams GREEDFLATION.

In fact, if there’s one thing that’s actually driving a long-term increase in U.S. egg prices, it’s new state regulations regarding the treatment of chickens. Leading the way in this regard is Rep. Porter’s home state of California, where a 2018 ballot initiative banned the sale of non-cage-free eggs. Today, the same carton of large white eggs that sells for $2.29 in Raleigh sells for $3.57 in Southern California. And other, similar regulations are on the way, including in Sen. Warren’s Massachusetts where a cage-free law took effect in 2022. Whether these regulations are good or bad is immaterial for today’s purposes (I’m generally ambivalent); but agricultural economists say they’re undoubtedly having an inflationary effect on U.S. egg prices that will increase further in the years ahead.

Team Greedflation’s Sudden Silence

Surprisingly enough, few if any of the Big Egg truthers have mentioned the industry’s increasing regulation (in their home states, no less)—or, even more tellingly, the recent and significant decline in U.S. egg prices. Sen. Warren and Rep. Porter, for example, haven’t tweeted about the issue since mid-February, and their official websites have nothing since then either. Reich’s last egg-related tweet was in late January. In general, the media have also gone quiet, save one very odd piece in The Economist which just parrots Farm Action and then adds at the end that prices have started to decline.

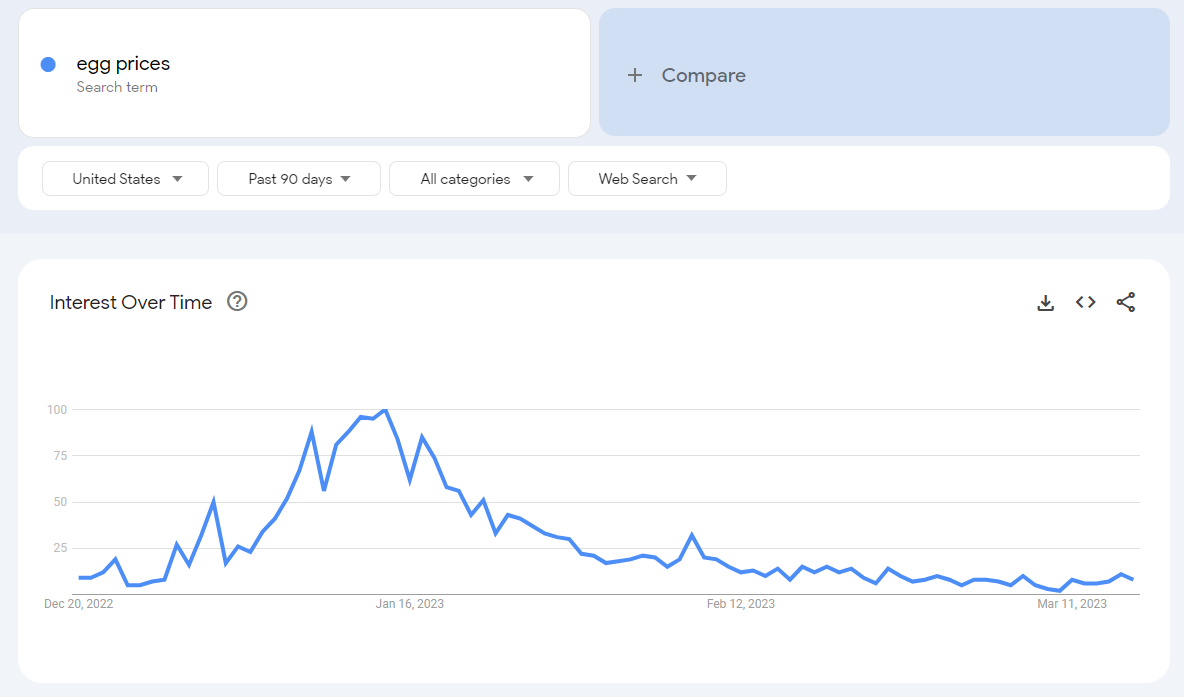

Waning media and politician interest likely reflects that regular folks have also stopped freaking out about eggs, almost certainly because prices have dropped (ha) and even some sales have hatched (ha ha):

Assuming that bird flu remains contained in 2023, we should expect further price declines and that the Great Egg Freakout of 2022 will become an increasingly distant memory. If so, it’s a solid bet the usual suspects will have long since forgotten about their past allegations and instead moved on to the next great greedflation conspiracy—one that conveniently justifies whatever ill-conceived economic regulation they just so happen to have already been championing anyway.

But just because they’ve forgotten, doesn’t mean we should.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.