With numerous provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 set to expire next year and renewed attention to the ballooning federal debt, U.S. lawmakers on the left and even some on the right have considered increasing the corporate tax rate, which the TCJA permanently lowered to 21 percent back in 2018. Most notable in this regard is President Joe Biden, who, along with many congressional Democrats, has supported raising the rate to 28 percent. Recently, however, Biden’s been joined by a small handful of Republicans in Congress—including Chip Roy in the House and populist Sens. Josh Hawley and J.D. Vance—who have either played footsie with increasing corporate taxes or openly supported a rate hike.

As the Mercatus Center’s Veronique DeRugy explained last week and as we covered here in Capitolism’s early days, the economics of corporate taxes are pretty well settled: They distort business decisions, are generally considered a poor way to raise revenue, and their ultimate burden falls not on the company itself but on a mix of its shareholders, workers, and customers, with economists disagreeing about the exact share each group bears. Nevertheless, tax hikers like Biden support increasing corporate tax rates because they do raise revenue and/or, thanks to voter ignorance of the economics, are easy to demagogue. (“Only a libertarian fundamentalist monster could be against taxing Big/Woke Corporations as much or more than American Workers!” Sigh.)

There is, however, another important—if unsaid—reason why many U.S. politicians want, even need, a high corporate tax rate: It lets them direct the economy via a favorite (if not the favorite) tool of central planners everywhere: targeted tax breaks, especially tax credits.

Corporate Tax Subsidy Growth Here and Abroad

As tax experts have long explained (and no, I will not bore you with details), not all “tax expenditures” are the same. On one side are benign and broad-based deductions or exemptions that remove economic distortions from the tax code and generally seek to treat similar corporations or individuals the same. On the other are tax expenditures—mainly credits but also certain deductions, exemptions, and preferential rates—that target specific people and firms and are specifically meant to drive certain economic activities. These special interest carve-outs and loopholes are dictionary-definition subsidies, and they have exploded in recent years, thanks to two big, somewhat-related things: 1) a rash of new industrial policy initiatives in the United States and abroad and 2) global negotiations to discipline taxation of multinational corporations through the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

We’ve already discussed Biden-era industrial policy initiatives repeatedly, so in that regard I’ll just reiterate that the three main laws at issue—the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), the CHIPS and Science Act, and (especially) the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)—are projected to deliver trillions of dollars in targeted tax credits in the years ahead. Looking at the U.S. Treasury’s estimates of energy tax expenditures, for example, my Cato Institute colleague Adam Michel estimates that total energy tax credits in the law could top $1.8 trillion over the next decade—a remarkable increase over the pre-IRA baseline and mostly going to U.S. corporations via various “clean energy” production and investment credits, as well as credits for “advanced manufacturing” and carbon capture:

Beyond just the IRA, Michel recently calculated that total U.S. industrial policy-related tax subsidies could hit $3.5 trillion over the next 10 years. (For perspective, total U.S. tax revenue last year was around $4.4 trillion.)

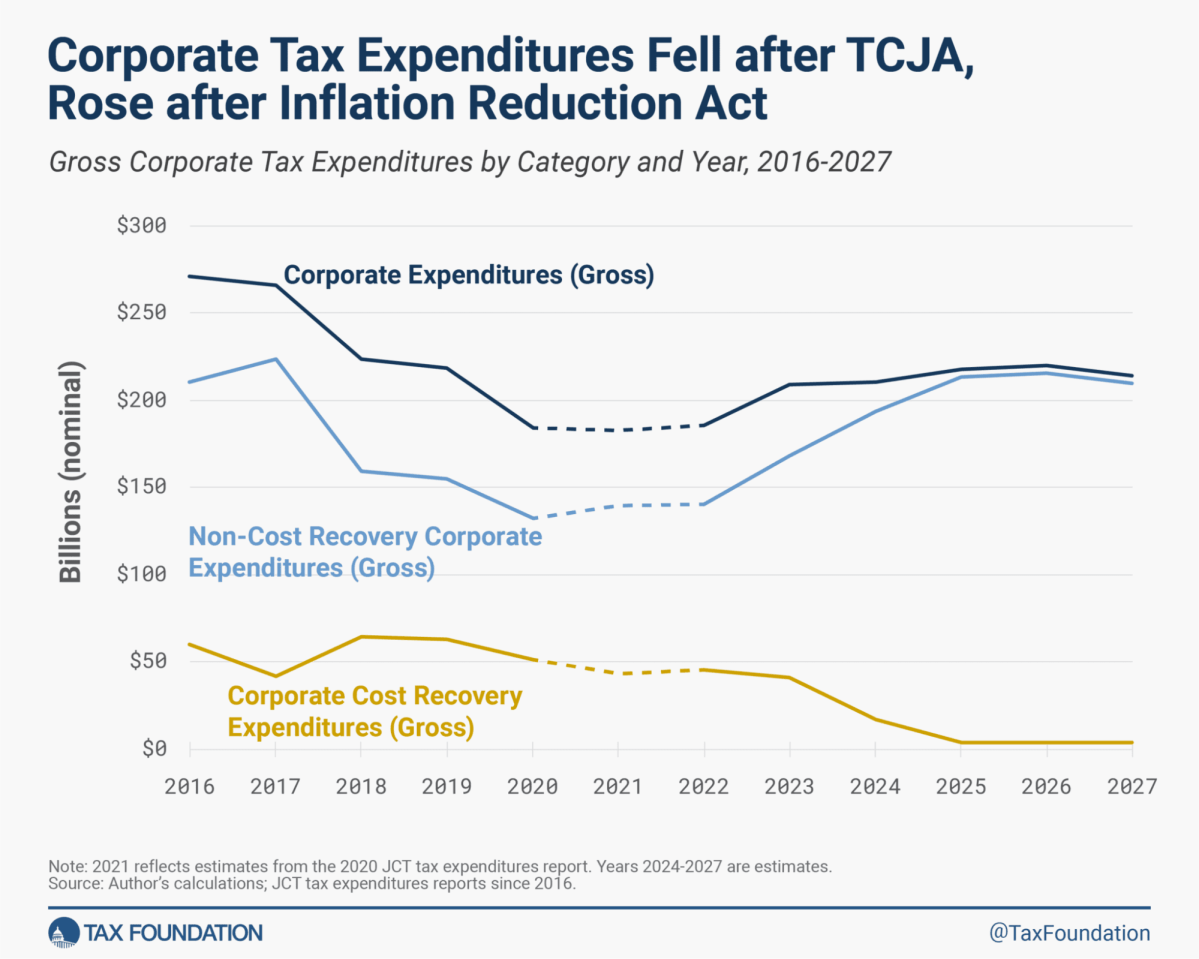

Michel’s total is just a projection, of course, but initial data show that the United States’ tax subsidy party indeed kicked off after the industrial policy laws were implemented in 2021 and 2022. My other Cato colleague Chris Edwards recently showed, for example, that corporate tax breaks in 2024 were almost double the level seen in the last pre-pandemic days of the Trump administration:

The Tax Foundation’s Alex Muresianu has further found that, as broad (non-discriminatory) tax deductions were being phased out in 2022 and 2023, “expanded tax credits for renewable energy production, renewable energy investment, and advanced manufacturing have increased non-cost recovery expenditures enough to push up total [tax] expenditures.” He adds that this is a “troubling” move “away from the neutral tax treatment of investment toward targeted, industry-specific tax subsidies” that will accelerate in the next few years:

The tax subsidies are flowing outside the United States, too. As we discussed a few weeks ago, American subsidies “prodded Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, the European Union, India, and other countries to offer subsidies of their own, while encouraging the Chinese government to double- or triple-down on its recent industrial policy schemes.” That’s trillions more in corporate subsidies (via thousands of new programs), with tax breaks again being a major vehicle for delivering them.

But industrial policy isn’t the only thing driving global tax subsidies these days. Instead, OECD negotiations to set a global minimum corporate tax rate have perversely encouraged governments to embrace tax subsidies to offset the competitive harms that higher corporate taxes might inflict on multinational corporations located or looking to invest in their jurisdictions. As the Financial Times explained last year:

The introduction of the [tax] reforms is also expected to increase tax competition between jurisdictions through credits, grants or subsidies. The OECD confirmed last year that the global minimum tax calculations will provide more favourable treatment for certain tax credits, notably some transferable credits contained in the US’s Inflation Reduction Act. Will Morris, global tax policy leader at PwC US, said investment hubs would be likely to collect additional tax revenue under the new regime and “give that back to business” via another arm of government. “Tax competition will not die — it will shift to subsidies and credits,” Morris said.

A recent analysis from the Tax Foundation’s Alan Cole explains the math here, which the Wall Street Journal’s editorial board helpfully dumbed down with some examples:

The calculations are abstruse… but the net effect is significant. Governments can offer the same low rate of effective taxation as before, at least for some companies, as long as the national treasury writes a subsidy check disguised as a refundable tax credit.

Ireland shows how this works. The annual budget Dublin introduced last autumn increased the refundable research-and-development tax credit to 30% from 25%, in order to partially offset the increase in Ireland’s top corporate rate to 15% from 12.5% when Dublin adopted pillar two.

Vietnam late last year imposed the new global 15% minimum tax on more than 100 foreign companies that previously paid effective corporate tax rates below 5% in some cases. But Hanoi already is crafting a web of cash subsidies billed as refundable tax credits for expenses such as training to help offset the tax blow. Bermuda is weighing what its government describes as a “robust package” of refundable tax credits to offset pillar two’s headline tax-rate increase.

Michel provides additional examples of this new system-gaming from South Korea, Germany, Singapore, and the European Union. Low-tax Switzerland is planning to do the same by allowing its member states (cantons) to spend additional tax revenue “on subsidies to attract and retain business.” A report from the Swiss arm of accounting giant KMPG summarizes the whole situation well: “While many may be celebrating [the OECD deal], the introduction of minimum taxation is in reality nothing more than a Pyrrhic victory. The battle for the lowest tax rates has given way to a ‘race to the top’ for state subsidies and grants.”

Thus, higher corporate tax rates have actually laid the groundwork for an explosion in tax subsidies similar to what we’re already seeing in the United States. And a global tax system ostensibly designed to raise revenue and prevent gaming by multinational corporations might very well end up doing neither (at best).

Heckuva job, everyone.

Tax Subsidies Need Higher Corporate Tax Rates (and Vice Versa)

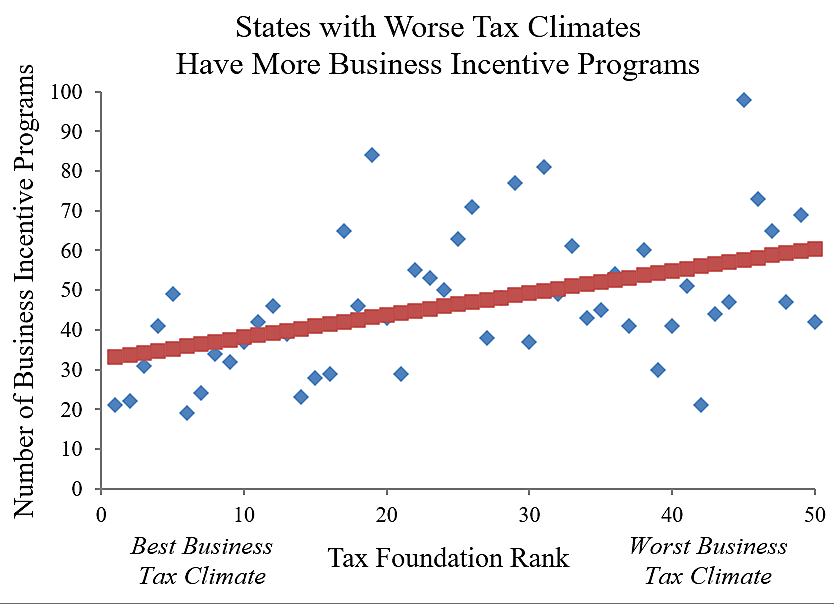

The recent OECD shenanigans are just the latest evidence of a clear linkage between higher corporate tax rates and tax-related subsidies. Here in the United States, for example, Edwards has looked at state-level taxation and finds a pretty solid relationship between more onerous corporate tax regimes (as ranked by the Tax Foundation, which generally advocates for lower corporate tax rates and fewer subsidies/loopholes) and more generous subsidies:

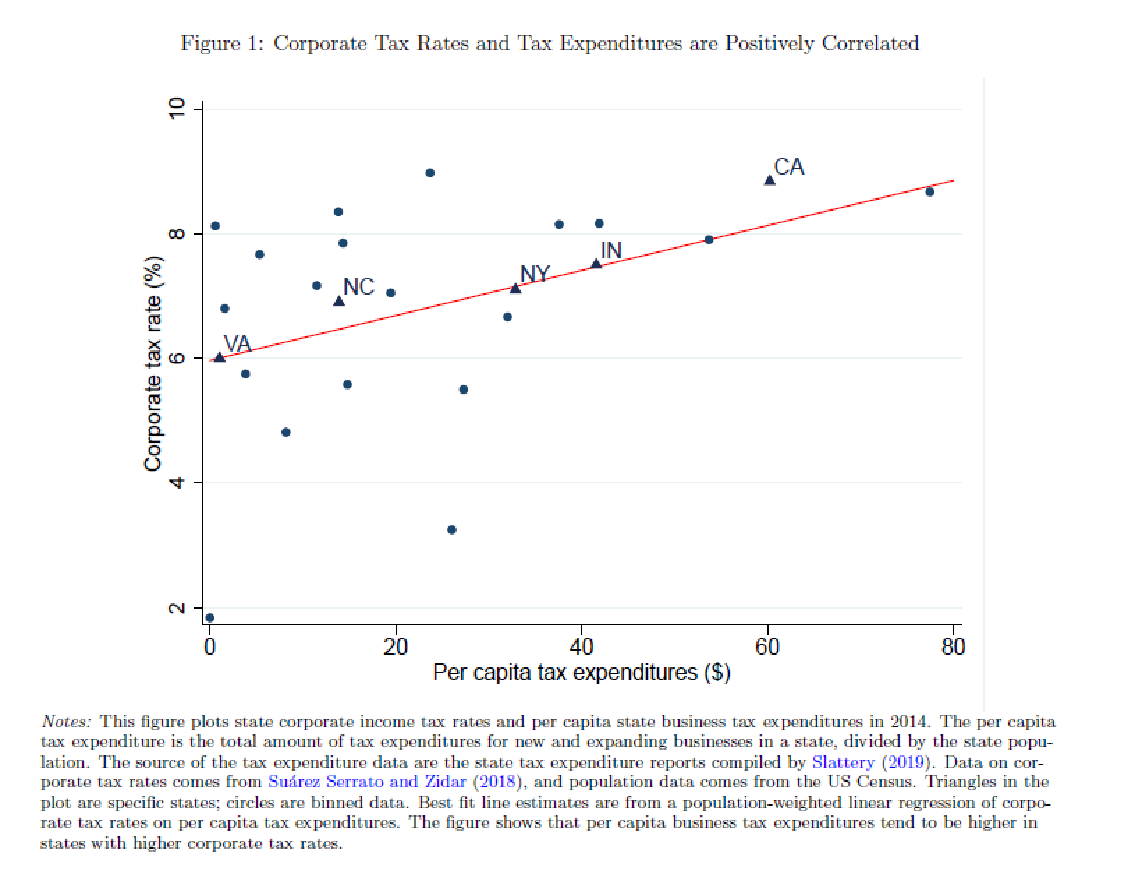

A 2020 paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research found a similar historical relationship, i.e., that “states with higher per capita incentives tend to have higher state corporate tax rates.”

Higher corporate tax rates are tied to tax subsidies for at least three reasons. The first is basic math: In a jurisdiction with low corporate tax rates, certain tax subsidies are less valuable to corporate recipients (and thus less effective at encouraging them to engage in certain activities). The easiest example is a state or country with no corporate income tax: A proposed exemption, deduction, or (non-refundable) credit is worthless because the corporate entity is already paying zero tax. The NBER paper’s authors explained the other end of the spectrum: “States with higher statutory corporate tax rates are able to offer larger tax incentives because the tax incentive serves to reduce the effective corporate tax rate.” The higher the effective tax rate, the bigger the tax subsidy’s effect—on both the beneficiary of the tax break and, it must be noted, the companies it’s competing against. High corporate tax rates are thus a necessary precursor to politicians using tax policy to reward their corporate friends or, as Sen. Vance once made clear, punish their corporate enemies. As the Washington Examiner’s Tim Carney just put it, “Higher tax rates and more complexity mean greater government control over corporate behavior. That means politicians and bureaucrats have more power.”

Second, and for similar reasons, big corporations often want higher corporate tax rates too. As Carney notes, a high rate “creates more jobs for political and policy insiders hired by corporations to game the increasingly complex tax code”—insiders that their smaller competitors can’t afford. Indeed, one of the dirty little secrets underlying populist shrieks about “Big Corporations” having high profits but paying little to no corporate taxes is that they often achieve this magic by taking full advantage of tax credits and other tax subsidies—i.e., by doing what many of those same shrieking politicians want them to do. The Berkeley Economic Review explains:

Tax credits, another major loophole used by a wide variety of industry sectors, are essentially incentives for corporations to incorporate certain practices within their business model. Some examples of these practices may be research and development, energy efficient appliances, and work opportunity credits. By stacking the wide variety of incentives available, companies such as Netflix, Prudential, and Activision Blizzard have saved hundreds of millions of dollars in income taxes.

Other examples of giant, often-demagogued corporations utilizing this kind of legal “tax avoidance” abound. You’ll thus be shocked to learn that, several years before the subsidy gravy train ends, corporate beneficiaries are already lobbying for more. In fact, a plugged-in friend tells me that Capitol Hill staffers are now frequently meeting with tax lobbyists pushing for all those “temporary” IRA tax credits to become permanent too. (History might not repeat, but it definitely rhymes.)

Smaller competitors often lack the resources to do the same kind of lobbying and tax planning, and—again—none of this nonsense would be possible if every U.S. corporation just paid the same low tax rate.

Finally, and as the OECD examples demonstrate, tax subsidies can help governments offset some of the economic harms that high corporate taxes impose on local economies—and in the process help politicians weather any voter blowback from those same harms. Edwards elaborates at the state level:

Leaders in these states favor raising taxes to increase spending, but they also want photo-ops at factory openings to highlight how their special-interest incentives are creating jobs. Politicians in high-tax states know that to attract investment under a bad tax structure they need to cut special deals. At the same time, politicians in low-tax states know that they do not need to dish out special-interest benefits because their economies are booming without them.

Of course, as almost any economist will tell you, special tax credits and other loopholes are a poor replacement for truly good tax policy. As the WSJ editors noted with respect to the OECD subsidy mess, policymakers’ tax breaks will lower multinational corporations’ operating costs, but at a high price: “tax rules will become more complex, will distort investment decisions more, and will be more prone to lobbying and special pleading.” (See Carney above on that last one.) The tax system will also be far more susceptible to abuse and outright fraud, as Michel recently documented with respect to the rampant, costly, and illegal shenanigans surrounding U.S. biofuel tax credits. That program’s certainly not the only U.S. tax credit scheme suffering from such problems.

With budgets and political capital finite, policymakers crafting future U.S. tax policy thus have a choice: a system of higher rates coupled with tax credits and other subsidies or one with lower rates, a broad base, and few special interest loopholes—i.e., precisely the type of corporate tax system that the TCJA, while surely imperfect, was trying to move us toward. If the policymakers care about growth, investment, and all workers’ incomes, their tax decision is easy:

If, on the other hand, they care more about buying votes, punishing enemies, ribbon-cutting photo ops, and economic engineering, they’ll want—nay, need—higher corporate tax rates.

No wonder the usual suspects are calling for them.

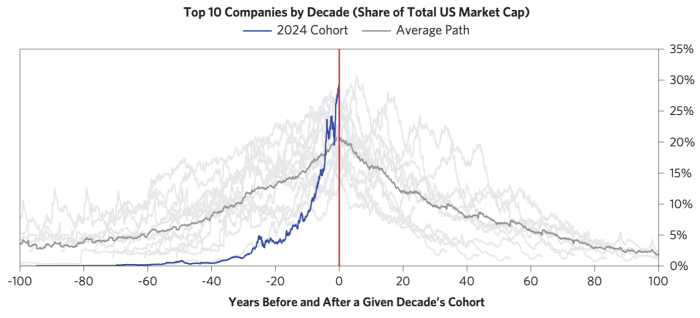

Chart(s) of the Week

The United States of Dynamism (top 10 companies don’t stay top 10 for long)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.