Some people will tell you that romance is dead. Not me.

As long as there’s a lib somewhere who needs owning, the flower of love remains in bloom.

Congratulations to the happy couple on their engagement, and more importantly on having “defeated” Pride Month. Someday their children will see that post and know that, at the moment their family was conceived, their father’s thoughts were properly occupied with taunting homosexuals.

As it happens, that now-viral tweet appeared one day before Gallup released a surprising new poll on attitudes about gay marriage. Well, not that surprising—at 69 percent, public support for legal same-sex unions is near its all-time high. It was still a minority proposition in the United States as recently as late 2011; less than a decade later, it reached supermajority levels and hasn’t looked back.

Look below the surface, though, and you’ll find a shift. Support for gay marriage has held steady among Democrats and independents since 2021 but dropped 9 points among Republicans over the same period, from 55 percent then to 46 percent now. Not since 2006-08 had GOP support declined two years in a row, but it did between 2022-24.

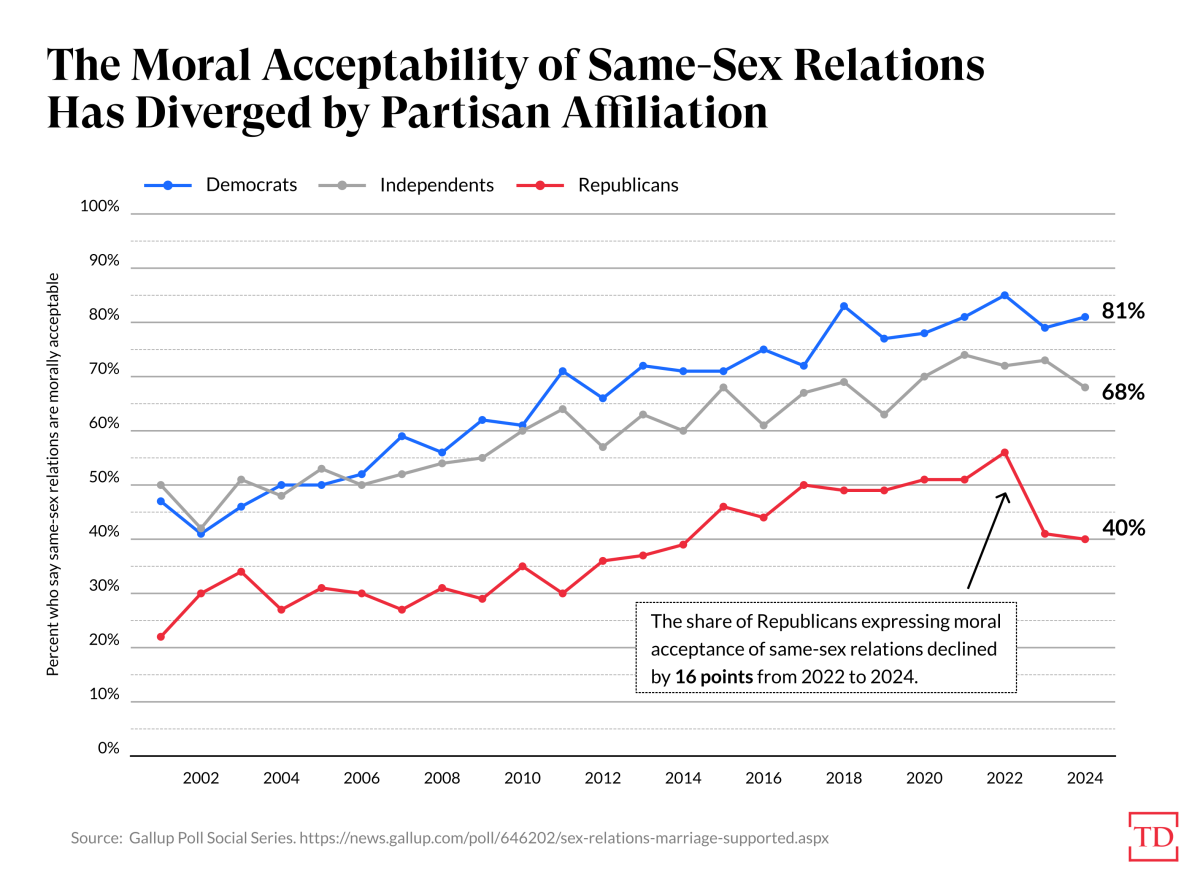

The drop is even steeper when Americans are asked whether gay and lesbian relations are morally acceptable:

Fifteen points among Republicans in the span of a single year is a big dip, enough to warrant a bit of thoughtful navel-gazing about what’s causing it.

“Easy,” you might say. “It’s a backlash to transgenderism being mainstreamed culturally and politically by the left.” There’s something to that, as we’ll see, but note that transgenderism has been pretty darned visible in the culture for the better part of 10 years. Yet Republican attitudes about gay marriage continued to grow more positive for most of that period.

“It’s also a backlash to gays suing Christian-owned businesses for refusing to cater their weddings,” you might add, but that runs into the same problem. The saga of Masterpiece Cakeshop, the most famous example of the phenomenon, began all the way back in 2012. The Supreme Court tackled it in 2018. Right-wing support for same-sex unions kept rising afterward anyway.

Something has been happening since 2022 to sour Republicans on the practice. What is it?

For starters, I think 2022 was the year social conservatives finally gained indisputable evidence that greater LGBT rights had led to certain pernicious policy outcomes.

The absence of that evidence has always been the fatal flaw in arguments against legalizing gay marriage. Critics struggle to explain why two people of the same sex marrying and potentially adopting children will leave society worse off instead of better. In particular, given their concerns over promiscuity among gay men, opponents have never squared the logical circle of wanting to exclude them from a domesticating institution like marriage.

No wonder, then, that the tweet with which this column began was so widely derided. It unintentionally satirizes the idea that gay unions pose any threat to straight ones: Why, just look at these heterosexuals getting engaged the way heterosexuals always have—during Pride Month, no less!

But things changed—a little—in 2022.

As noted above, mainstream acceptance of transgenderism has been rising for the better part of a decade alongside rising GOP support for gay marriage, and for largely the same libertarian reason. Just as same-sex unions imposed no burden on straight ones, men transforming themselves surgically into women and vice versa imposed no burden on the general population.

Until it did. 2022 was the year that trans women outcompeting women in sports broke big.

The chief offender was Lia Thomas of the University of Pennsylvania, who earned middling results for years on the school’s men’s swim team while transitioning, then competed for the women’s squad and promptly became a national champion in the 500-yard freestyle. Later, Penn went so far as to nominate Thomas for the 2022 NCAA Woman of the Year award. The spectacle of a broad-shouldered, 6-foot-1 swimmer putting female teammates and competitors to shame in the pool plainly convinced many Republicans that the “victimless” process of changing genders wasn’t always so victimless.

That was also the year that the mainstreaming of transgenderism began showing up in children’s attitudes about gender. One study released that summer, for example, found the number of kids who identified as trans had nearly doubled in a few years. Progressives would probably chalk that up to the taboo around the subject relaxing over time—i.e., kids may have become more willing to confess their gender dysphoria as society has become more accepting of it, but they haven’t become more likely to have gender dysphoria.

But conservatives would counter that children are famously impressionable and susceptible to peer pressure. By treating transgenderism as a new civil-rights front and celebrating the bravery of transgender people in media, the left created a predictable social contagion that was destined to influence children—sometimes in garish ways. As reports of teenagers undergoing gender-reassignment surgery proliferated in 2022, the right again had reason to question the conventional wisdom that transgenderism is a “victimless” process. How victimless can a fad be if it leads to a 15-year-old boy’s castration?

Not coincidentally, 2022 was likewise the year that the second-most popular Republican in America began aggressively using this right-wing backlash to his advantage.

Ron DeSantis became a star populist during the pandemic by resisting pressure from the scientific bureaucracy and the teachers’ unions to close public schools. Between that and his budding romance with anti-vaxxism, he had gained enough traction politically by the end of 2021 to become a credible contender for the Republican presidential nomination. Predictably enough, he began looking around for other battles he might pick with the right’s traditional enemies to prove that he, not Donald Trump, would be the better “fighter” in 2024.

He landed on LGBT rights, also predictably given grassroots Republicans’ growing alarm at transgender excesses. DeSantis signed Florida’s so-called “don’t say gay” law in March 2022; when Disney offered mild criticism of it, the governor eagerly declared war on the company. Other laws targeting drag shows, setting rules for using gender-specific bathrooms, and discussing pronouns in schools would follow in 2023, as he tried to pander his way into becoming the champion of culture-war populists in the Republican presidential primary.

It didn’t work out. But by using his considerable megaphone to focus populists on the allegedly corrupting influence of LGBT constituencies, he surely encouraged some right-wingers to reconsider gay marriage.

There’s one more thing that happened in 2022 that might not seem connected to gay rights but is—sort of. The Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

Gay couples have less interest in the end of constitutionally guaranteed abortion rights than straight couples do, for obvious reasons. But the end of Roe hurt them in two ways politically. First, it left social conservatives in need of a new animating cause after 50 years of rallying against judge-made abortion laws. Second, it showed Republicans that they’re not perpetually doomed to lose the culture war in all matters involving sexuality.

The imagined “one-way ratchet” in the Constitution toward ever looser sexual morals turned out to operate two ways. Conservatives can move the Overton window. “We are the first generation to give our daughters fewer rights than we had,” Jill Biden told a crowd in Pennsylvania this past weekend, a thought that’s occurred to some ambitious social conservatives lately too, I’m sure. And doubtless, it left them wondering which other supposedly untouchable rights might turn out to be touchable after all.

The right to contraception? Clarence Thomas has already proposed revisiting that one, but contraception is very popular and has been protected by the Supreme Court since the 1960s. Abortion rights are (or were) almost the same age and have proved popular enough to send Republicans down to defeat in one ballot referendum after another since Roe was overturned.

But gay marriage is much newer. And unlike abortion and birth control, it involves a small minority of the population whose sexual behavior remains off-putting to many conservatives. The grassroots right is forever in search of a new enemy. Why not gays?

The obvious answer to that question is, “Because support for gay marriage is at 69 percent!”

Fair enough. The singular policy fact of Trump’s 2024 campaign is that he refuses to let social conservatives’ preferences steer him off an electoral cliff. Public support for abortion rights turned him into a moderate on that issue; public support for gay marriage rights will ensure that he’s a moderate on that too.

Or “remains a moderate,” I should say. For all his demagoguery on other topics, Trump has never been much of a bomb-thrower when it comes to LGBT issues.

In fact, one way to look at the Gallup data above is in terms of how little change there’s been among Republicans on gay marriage over time. For nine years the GOP has grown increasingly feral toward its traditional political enemies—yet it still nearly musters majority support for same-sex unions.

Maybe there’s an age effect to that, as younger Republicans have grown up in a culture in which gays are thoroughly normalized. Convincing them to change their minds about same-sex unions will take more work than convincing their grandparents to do so.

Or maybe the thought of re-banning gay marriage is distasteful for many Republicans. Banning abortion is comparatively easy as a moral matter because the burdens imposed on women by doing so are balanced by the virtues of protecting innocent life. Banning same-sex unions has no such counterweight. Nullifying marriages would tear families apart out of simple animus for their sexual identity.

Or, God help me, maybe Trump deserves a little credit for gay marriage’s enduring popularity on the right. Had he scapegoated gays aggressively as a cultural enemy a la DeSantis, I’m sure he could have driven Republican support for same-sex unions lower than it is now. Fortunately for gays, he has many other scapegoats he’d rather attack—immigrants, the justice system, the “deep state,” the media.

“It could be worse” is how I read the Gallup data. How often do you hear me say that?

But it could also plausibly get worse. Which is something you hear me say a lot.

Revolutions have their own momentum. Despite Trump’s best efforts to divert populist hostility away from gays and toward political enemies who threaten him directly, the impulse toward cultural revanchism that he’s cultivated in his supporters won’t necessarily follow the course he’s set for it after he’s gone. “Making America great again” means different things to different strains of post-liberalism, after all.

Because he and his acolytes have been so keen to use religion as a vehicle for populism, it may be that a post-Trump GOP will swing more heavily toward religious demagoguery than Trump himself would expect or be comfortable with.

A few weeks ago, NBC News tracked the devolution of uber-grifter Charlie Kirk from someone who believed in the separation of church and state circa 2018 to someone who now derides the idea as a “fabrication” made up by “secular humanists.” Not surprisingly, Kirk has also become an enemy of the “LGBTQ agenda” over the same period. His turn toward Christian nationalism is partly a cash grab—as everything in which he’s involved is—but it’s also a matter of shrewdly coopting an enormous extant community of Christian believers for political ends.

“I think that maybe someone like Charlie Kirk has kind of decided that Christianity is the best way” to advance a populist agenda, a history professor at Hillsdale College told NBC News. “I don’t think that people wake up and say, ‘Oh, well, [I’m] Christian now, that’s why I’m going to be populist.’ I think they are populist, and maybe they use Christianity as a buttress for it.” Another scholar put it more bluntly to the Washington Post: “The religious right is the pawn, and MAGA is the king.”

What happens when MAGA, in the person of Trump, is no longer the king?

Trump loves Christian nationalism because he relishes blind obedience. The cultier his movement becomes, festering with prophesies about his return to power and the smiting of evil, the more assured that obedience is. He stokes their zealotry with laments about his martyrdom and apocalyptic pronouncements about the “final battle” that’s coming. He thinks he can ride this tiger—and maybe he can, with no grassroots revolt on the right if he opts for moderation as president on matters like abortion and gay rights.

But someday when he’s gone, would any of us be surprised if the fusion of religious goals with political ones that he’s encouraged leads the Christian nationalist movement that survives him to make rescinding gay rights a priority? A post-Trump GOP base will need a new casus belli. Before Trump entered politics, it was ending big government; in 2016, it became draining the swamp; now it’s keeping out foreigners and taking “retribution” against the deep state. Why wouldn’t same-sex marriage be the next silver-bullet explanation in 2028 for what’s causing America’s ruin?

Undoing it would be a long-term project, as federal protection for the practice was codified (in 2022, ironically) with the support of 13 Republican senators. Gay marriage might never again be a 50-50 issue in polling. But with enough time and effort from the right-wing consensus machine, it can get a lot closer to the usual extreme polarization we’re all familiar with than it is now.

Despite the illiberalism of the modern right, it’s easy to believe that Christian nationalism is unserious because the man at the center of it has only ever used the Bible as a political cudgel or inventory to be moved. But it needn’t be that way forever. The next demagogue will inherit a party in which some significant chunk of the base has been primed to let their faith dictate their belief in which rights other Americans should and shouldn’t enjoy. If gays aren’t worried about that, they should be.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.