My mother asked me recently what would happen if Donald Trump were convicted of a crime and then elected president. Would he command the military from inside a prison cell? Would his Secret Service detail be incarcerated with him? Could he pardon himself?

As the (ugh) lawyer in the family, I’m supposed to know. I didn’t, because no one does. The idea of American voters handing presidential power to an inmate is so darkly absurd that the Founders didn’t think to address it.

If we could travel through time and warn James Madison to provide some guidance in the Constitution about how a coup-plotting criminal might be expected to faithfully execute the laws, I imagine he’d stop work and tear up the document. There’d be no point in continuing. A people corrupt enough to force such a dilemma on themselves will abandon the Madisonian project in due course.

The scenario in which Trump is reelected president while the federal cases against him remain pending is just as absurd and arguably darker. David Frum considered it in a piece for The Atlantic published on Tuesday. The first months of a second term would be consumed by Trump's attempt to pardon himself, Frum notes. If the Supreme Court rejected it, he’d resort to ordering the Justice Department to dismiss the charges against him. Prosecutors there would (hopefully) refuse and resign; the department would empty out; Trump would move to fill the vacancies with cronies like Jeffrey Clark and Sidney Powell, who themselves might require pardons to free them from prison before they get to oversee federal law enforcement. The Senate (hopefully) would refuse to confirm said cronies, triggering another crisis.

Meanwhile, the state criminal charges against the president in New York and, potentially, Georgia would continue to move forward.

“A second Trump presidency would offer only division, chaos, and paralysis that would never be quieted,” Frum observes. Informed that We The People could soon very plausibly choose such a fate, Madison might understandably ditch the revolution and re-pledge his allegiance to George III.

Frankly, once he saw the man for whom all this constitutional fuss is being made, he might join the British army.

Some Trump critics celebrated Tuesday upon learning that he was being indicted for crimes related to January 6. Former judge J. Michael Luttig did not. “These events … will forever scar and stain the United States in the eyes of the world,” he wrote on Wednesday, lamenting that a criminal trial of a former president for trying to overturn an election should ever be necessary. “Never again will the world be inspired by America’s democracy in the way that it has been inspired since America’s founding almost 250 years ago.”

I don’t know about that. If you’re wasting away in one of the world’s many autocracies, dreaming of migrating to the United States, the legal circus around Trump’s coup plot probably won’t dampen your enthusiasm. But I do share Luttig’s judgment that the political reality of this moment, with Trump speeding toward prison and a third presidential nomination, can’t help but shake one’s faith in America beyond repair. How good can a country really be if it would do this to itself for a figure as rotten as him?

Part of me even thinks that it doesn’t matter who wins the election. It does, of course—a lot, as Frum explains—but the fact that we’re this far down the road of civic disintegration and seemingly prepared to go much further is cause for despair even if we don’t go quite far enough to elect Trump president again.

We’re not coming all the way back from this.

My thoughts on Indictment 3.0 are less linear than kaleidoscopic. One thought is that this indictment was necessary even though it’s weaker on the merits than Indictment 2.0 was.

“A trial relying on vague laws to prosecute a presidential candidate who may well have believed the lies that assured him that he wasn’t a loser is the last thing this country needs,” my colleague Sarah Isgur argues this morning in our newest newsletter, The Collision. I take the point, but would counter that the last thing this country actually needs is for an authoritarian cult leader to escape accountability for a putsch attempt where probable cause exists to believe he committed multiple crimes—all because the cult might react badly if he doesn’t.

The future coup-plotters of America must be deterred. Until yesterday, there was nothing to deter them.

On the contrary. Judging from primary polls, right-wing voters seem to view attempting a putsch as an asset in a future presidential nominee more so than a liability. After the 2020 election they showered Trump with a quarter of a billion dollars—that’s billion with a B—to fund his phantom legal defense fund. The foot soldiers who ransacked the Capitol on his behalf are viewed as folk heroes by much of the GOP base while Ashli Babbitt, who was shot dead trying to breach the House chamber, has become a sort of religious martyr. Senate Republicans, who could have disqualified Trump from holding office and spared us all of [gesturing broadly] this, wilted under partisan pressure when given the chance.

All of that has conspired to give the putsch-plotters of tomorrow every incentive to try to seize power illegally again. Or had, I should say.

Indictment 3.0 will make them think twice, just as the hundreds of criminal cases brought against insurrectionists since January 6 made rank-and-file MAGA fanatics think twice about acting out after his first two indictments. Even if Trump ends up being acquitted at trial, the fact that he’ll have come thisclose to imprisonment may sober up the next generation of autocrats, knowing that they might not be as lucky in court. Chances are good, in fact, that cronies like Clark and Powell who are plainly in Jack Smith’s crosshairs won’t be so lucky. Trump’s political disciples will emulate his lowest moment at their legal peril.

To borrow Jonathan Last’s formulation, Indictment 3.0 is the FAFO indictment. Because The Dispatch is a family site, I’ll leave you to google that acronym if you’re unfamiliar. It should suffice here to say that Donald Trump has done a lot of FA-ing and that the time for FO-ing has arrived at last, as it should and must. Let the dictator wannabes among us take note.

We twist the kaleidoscope and arrive at another thought: Anyone who thought right-wing influencers might treat the new indictment differently from the previous two is a fool.

Some analysts wondered whether criminal charges related to January 6 might hit harder among prominent Republicans and not just because some were at risk of being murdered by Trump’s “patriots” at the Capitol that day. Practically every figure of note in the GOP and its media organs condemned the insurrection as it played out, and so they might feel obliged for the sake of consistency to be more circumspect about Indictment 3.0. Vivek Ramaswamy, for instance, tweeted in the days following the riot at the Capitol that “What Trump did last week was wrong. Downright abhorrent. Plain and simple. I’ve said it before.” Elsewhere he called the episode “disgraceful” and “a stain on American history.”

Tuesday night, reacting to the new charges, Ramaswamy had changed his tune. “Donald Trump isn’t the cause of what happened on January 6,” he insisted. “The real cause was systematic and pervasive censorship of citizens in the year leading up to it. If you tell people they can’t speak, that’s when they scream.” That logic is identical to how progressives rationalized riots after the murder of George Floyd, Reason reporter C.J. Ciaramella pointed out, amazed. Jonah Goldberg complains often and correctly about how the not-so-New Right has adopted the left’s worst modes of thinking; we can now add their belief that “riots are the language of the unheard” to his list.

If Ramaswamy was willing to reverse himself so shamelessly about Trump’s culpability in January 6, there should be no limit to the excuses less compromised Republicans might be willing to make. And there isn’t, it turns out. I spotted at least six different reactions to the indictment among the usual suspects on social media after it was released, some more persuasive than others. But none very persuasive.

The DOJ has been weaponized. This was the preferred pro forma spin for Trump’s opponents, from bad Republicans like Ron DeSantis to supposedly “good” ones like Tim Scott. Among Trump’s credible challengers for the nomination, only Mike Pence opted against yammering about the deep state to say something disapproving about his behavior on January 6, for obvious reasons. The fact that Trump’s competition senses that more harm than benefit would come from attacking him over the indictment should be proof enough that the Republican base won’t hold it against him.

Holding the trial in D.C. is unfair. Despite the fact that the Sixth Amendment requires defendants to be tried in the jurisdiction where the crime was committed, many Republicans—again, some of them Trump’s own opponents—insisted that he can’t get a fair hearing in a Democratic stronghold. Never mind that voir dire exists to screen jurors for political bias; to many on the right, “a jury of one’s peers” evidently now means a jury of Republicans (or Trump voters?), not Americans. As it happens, the federal judge in Trump’s case is African American, a woman, and an Obama appointee, all of which is destined to soon be treated as further evidence of “unfairness,” most vocally by the defendant himself.

This is a civil war. Keyboard warriors among us didn’t bother with legal niceties, preferring instead to rant about the Justice Department having become a “domestic terror organization,” etc. Perhaps they’ll succeed in inspiring someone to blow something up in protest, perhaps not. Hope for the best, expect the worst.

Whatabout Hunter? The fact that the indictment was handed up the day after the House GOP held another hearing into Hunter Biden was noted by many, and not just the most clownish populists. Kevin McCarthy was quite exercised about it, for instance. As far as complaints about the timing go, though, I find myself more sympathetic to Donald Trump Jr.’s gripe that it should not have taken two and a half years to bring these charges. Junior believes the Justice Department dragged its feet deliberately in order to complicate Trump’s 2024 campaign; the truth is more proasic but it is true that Merrick Garland dragged his feet. Now that the indictment has splashed down into the middle of a Republican primary, perceptions of its legitimacy will suffer accordingly.

Trump’s “stolen election” rhetoric was protected speech. It’s true that everyone has a First Amendment right to say that the 2020 election was rigged, just as it’s true that everyone has a First Amendment right to say “I wish my wife were dead.” But context matters. If you say “I wish my wife were dead” while slipping a thousand bucks to a hit man, it’s to prison you’ll be going. Likewise, if you say “the Republican slate of electors should falsely certify that the Republican won the election in their state,” that’s protected speech—unless, perhaps, you happen to be the Republican in question and you’re saying it to those electors while they’re plotting to do exactly that. Those who blithely insist that Trump can’t be convicted for words alone are misleading you, notes attorney Ken White.

Trump honestly believed the election was stolen. “Good luck proving that Trump knew he lost the election, when he—whether behind closed doors or in public, whether with one person or massive crowds—has consistently maintained that he won with an apparent passionate sincerity,” Rich Lowry tweeted. It’s a fair point. How might you prove specific intent to defraud if the defendant ended up talking himself into believing sincerely that he’s the one who’s been defrauded?

One thing you could do is show that Trump did seem to believe that he’d lost, at least at times. “You’re too honest,” he told Mike Pence when Pence claimed he had no authority to block the certification of electoral votes. “Just say that the election was corrupt and leave the rest to me and the Republican congressmen,” he urged acting Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen. Allegedly he described some of his own lawyers’ conspiracy theories about vote-rigging as “crazy.”

Only God and Trump himself know to what extent his brain is capable of separating truth from fiction when the truth cuts against his interests. But there were, it seems, at least glimmers of awareness periodically that Biden had won. ("Can you believe I lost to that f—ing guy? That f—ing corpse?") Smith might be able to prove that Trump knew the truth. Certainly he can prove that every trustworthy figure within a country mile of him knew it, and told him so.

But even if he can’t, pause here and reflect that the “Trump really believed this insanity” insanity defense is being offered on behalf of a person who’s 35 points ahead in the Republican presidential primary. Much of the right will soon be claiming simultaneously that he can’t be convicted because he can’t distinguish self-serving delusions from reality—and also that he should be president again, with America’s nuclear arsenal at his command.

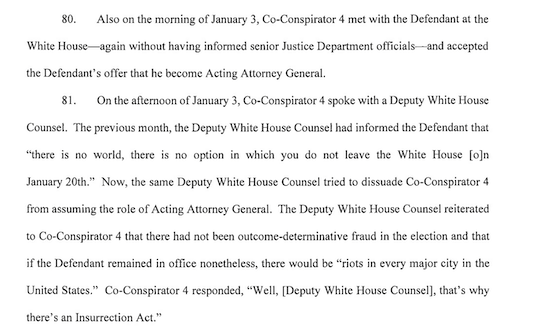

Reflect also on the fact that, while even “good Republicans” were rolling their eyes at the allegations in the indictment, this passage was circulating on social media. “Co-Conspirator 4” is Jeffrey Clark, the man to whom Trump wanted to entrust the Justice Department and to whom he might one day turn again:

That’s how close we came to martial law being invoked to suppress a potential uprising against Trump’s coup. Yet activist Republicans are consumed by the political vagaries of the jury pool in D.C.

The American right is a wrecked culture. Top to bottom, it’s lost its capacity for moral reasoning where political priorities, particularly Trump’s continued viability, are involved. If nothing else good comes from the indictment, the Republican reaction it elicited at least provided some more clarity about that. Trust these people with power, whether in Trump’s hands or someone else’s, at your own risk.

One more twist of the kaleidoscope: No matter what happens now, the 2024 election will be shattering. We’re not coming all the way back from it.

If, after all this, Republicans manage to return this cretin to the White House, no one to the left of Trump himself will look at the party or the country the same way again. I certainly won’t. I don’t know how American politics will function during a Trump second term, frankly, if he prevails after having been convicted of a crime or pardons himself from charges that are still pending. The shame and disillusionment would define a generation. For Republicans to gamble on Trump in 2016, not knowing how he’d behave as president, was a mistake; to hand power back to him in 2024 after learning the hardest possible lesson of what he’s capable of would be something like a crime in itself, de facto ratification of the putsch. It would break the social contract.

If, on the other hand, Republicans fail to return him to the White House, that will also be destructive.

Any outcome that ends with someone other than Trump as president at this point will be treated by his fans as illegitimate. That was always going to be the case, granted, but multiple indictments have given the logic extra potency. Trump’s campaign treasury is being sapped by legal expenses; his time on the trail will be limited by court obligations; his favorability among the general electorate, always low, is destined to sink lower. Many Republicans who eschew the strong-form “rigged-election” theory of 2020 nonetheless endorse a weak-form version in which the media, by refusing to take the news of Hunter Biden’s laptop seriously, and state courts, by expanding voting rules without legislative authority, put a thumb on the scale that proved decisive. If Trump voters were willing to deem Biden illegitimate for reasons as lame as that, imagine how they’ll react to Trump losing narrowly after being burdened by three (soon, four) indictments obtained by Democratic prosecutors.

It would be best for the GOP and for America if it didn’t come to that. Better to break the party than the country by having Republican primary voters choose a different nominee over the objections of Trump fanatics. If the right is hellbent on sticking with a boorish authoritarian, there’s a much younger, much smarter Trumpy populist in the race. They can have him and shed all of Trump’s criminal baggage, turning the election back into a choice between policy visions instead of what it seems destined to become, a relitigating of the 2020 election.

But they don’t want that younger, smarter populist, it seems. Fundamentally they’re no longer as invested in governing or even in holding power as much as they are in delegitimizing the left. A Trump victory, thwarting the “deep state’s” bogus prosecutions, or a Trump defeat, producing another “illegitimate” Democratic win, would gratify that impulse more than anything Ron DeSantis could do for them. It’s the only explanation for why populists would rather plunge into the legal chaos of a Trump second term like Frum describes than embark on a serious policy drive via a first DeSantis term. They don’t want their enemies beaten or forced to live under right-wing laws, ultimately. They want them disgraced.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.