Here’s something you don’t see every day.

It’s rare for a federal judge to appear on a news program for any reason. But to appear on one for the purpose of criticizing a party in an active case was so extraordinary it rendered my colleague, Sarah Isgur, nearly speechless.

“This is a sitting federal judge commenting on a criminal defendant in a pending trial in his district,” she tweeted in reaction to the news. Not a word of that sentence is overtly critical, but it didn’t need to be. Merely describing what had happened conveyed the depth of her astonishment.

Res ipsa loquitur, to borrow a phrase from the law.

If it matters to you, Reggie Walton is a senior judge rather than an active judge, which means he hears cases on a reduced and irregular schedule for the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. He isn’t presiding over Donald Trump’s criminal trial in Washington for trying to overturn the 2020 election; Judge Tanya Chutkan is in charge of that. And if you watch the interview he did with Kaitlan Collins, you’ll find that he spoke mainly in generalities about threats to judges instead of focusing on Trump.

But so what?

The context for the CNN segment was Trump’s attempt to intimidate the judge overseeing his upcoming criminal trial over the Stormy Daniels hush-money payoff. Collins made that explicit on social media:

Judge Walton understood that context. He knew, of course, that Trump is a criminal defendant right now not only in his home district but in Florida, Georgia, and New York. He must have recognized that prospective jurors in each of those venues might see the interview and have their views of Trump’s guilt colored by a notable judge’s dim regard for his behavior.

As you may have heard, Trump is also the Republican nominee for president. Even if no jurors end up being influenced by Judge Walton’s interview, some voters very well might be. Federal judges aren’t supposed to be campaigning against candidates for office. So what was he doing on CNN?

Canon 2 of the Code of Conduct for United States Judges urges jurists to “act at all times in a manner that promotes public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary.” Canon 5 warns them against engaging in “political activity.” Whether or not Judge Walton’s conduct ran afoul of either is above my pay grade, but the appearance of impropriety was glaring enough for numerous Trump boosters to complain loudly about it online.

How seriously should we take them?

One of my editors described Judge Walton’s appearance as the latest in a series of “broken clock” moments for Trump’s critics. A broken clock is right twice a day, the saying goes; insofar as Trump reflexively whines about corruption and unfairness after every setback he faces, most famously following the 2020 election, he’s a broken clock.

But sometimes, Trump’s antagonists overreach by making special exceptions to institutional norms just for him. When they do, the broken clock appears correct, leading many Americans to wonder whether it’s actually as broken as his critics say.

The reasons for that overreach vary.

Sometimes, the missteps are a matter of earnest gullibility driven by understandable suspicion, as happened when some media outlets published the Steele dossier without affirming the truth of its contents. A special exception from standard journalistic practices was made for Trump because his apologetics for Vladimir Putin are genuinely weird and because he appears amoral by nature to a degree that no U.S. president, Richard Nixon included, has ever been. If any commander-in-chief might plausibly be jungled up with the Kremlin, it’s him.

So a special exception was made. And when it didn’t pan out, the broken clock that’s forever complaining about the media being out to get him seemed correct.

Suppression of the Hunter Biden laptop story by Twitter and Facebook in October 2020 falls into the same bucket. A special exception to platform rules was made because it seemed only too likely that Russia was once again trying to lend Trump a hand in the home stretch of an election. Liberals weren’t about to let that happen with victory within reach; the laptop story was suppressed on the assumption that it was enemy disinformation or, at the very least, the product of hacking.

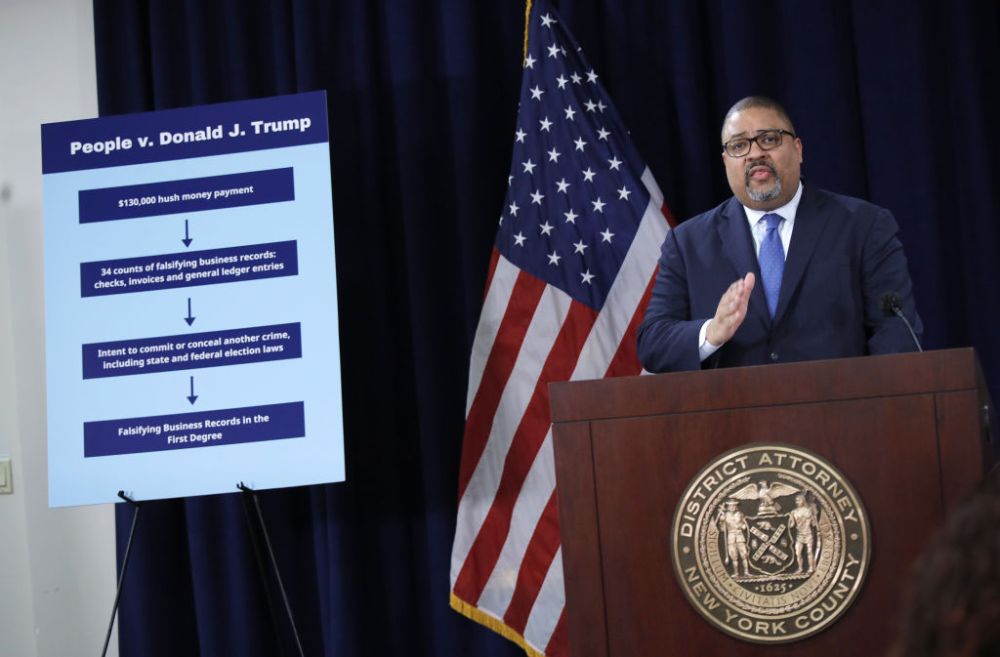

It wasn’t. The broken clock was right.

Sometimes, it’s personal ambition that causes overreach. Prosecutors keen to make a political name for themselves have always eyed high-profile suspects hungrily, but Trump is a historically juicy target due to the animosity Democrats feel for him and the freakishly high political stakes of a conviction before November. Some of his antagonists have gotten sucked into that and dropped the pretense that they’re dispassionately applying the law, instead playing to the cheap seats. Witness Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis warning Trump that “the train is coming” for him, the sort of thing you might hear at a pro wrestling event. Or consider New York State Attorney General Letitia James doing the legal equivalent of end zone dancing by posting daily updates online of how much interest Trump owes in the civil judgment against him.

The broken clock says he’s being persecuted by corrupt, hyperpartisan Democratic lawyers for political gain. Sometimes he seems correct. The fact that Willis has gotten sidetracked by a garish ethical scandal of her own making only seems to drive the point home: Why should Donald Trump pay a legal price for his misconduct when those who sit in judgment of him are compromised themselves?

No wonder that Americans’ views of his criminal culpability have changed.

Insofar as Judge Walton’s CNN interview was another “broken clock” moment, though, neither ambition nor gullibility explains it. I think it’s a matter of sincere exasperation. And while that doesn’t excuse it, it does make it relatable.

On some level, this newsletter is a product of the same sentiment. The reality that half the country is comfortable enough with how Trump behaves that they’re willing to entrust the presidency to him again is so shattering and disillusioning that I often retreat into the belief that they simply mustn’t know how bad he is. I’d better tell them! (And tell them, and tell them, and tell them.) Those of us opposed to a second Trump term can rationalize the current polling by speculating that Americans haven’t paid any attention to what Trump has been up to since 2021 and that they’ll snap out of their stupor soon enough. Ignorance, not indifference, is to blame.

Maybe. But it may also be that they do have some sense of what he’s been up to yet have chosen to remain willfully ignorant about the particulars so as not to create any pangs of guilt before they go out and vote for him again. They know the clock is broken, but they don’t care—and don’t care to be reminded of it.

In their heart of hearts, some might even admit that it’s the brokenness that attracts them.

I can’t read Judge Walton’s mind, but I imagine him finding Trump’s intimidation tactics in the New York case—which now include mentioning the judge’s daughter by name—so far beyond the pale that he concluded some extraordinary measure needed to be taken to alert the public. Threats against judges and prosecutors have been commonplace during Trump’s legal travails, yet Republican voters handed him their party’s presidential nomination anyway almost by acclamation. How is that possible? Can it be that they hadn’t heard anything about them when they cast their ballots for him?

They simply mustn’t know how bad he is, Judge Walton might have figured. I’d better tell them—even if telling them, in this case, meant committing a breach of judicial ethics, proving the broken clock correct once again about American institutions ditching their usual rules to go after Trump.

This is all very conflicting for a Never Trumper.

J. Michael Luttig, a conservative and a former judge himself, commended Walton on Friday for speaking up to try to protect the judiciary from Trump’s goonish tactics “because no one whose responsibility it is to do so has had the courage and the will.”

Luttig went on to say that the United States Supreme Court and its counterparts at the state level should be taking the lead on this, but ultimately, he laid the blame where it belongs: “It is the responsibility of the entire nation to protect its courts and judges, its Constitution, its Rule of Law, and America's Democracy from vicious attack, threat, undermine, and deliberate delegitimization at the hands of anyone so determined.”

That’s correct, but the nation—or half of it, anyway—has chosen to abdicate that responsibility. How far should institutional actors go in bending their own rules to try to pick up the slack and/or spur that wayward half into caring again?

Forced to choose, I prefer Sarah Isgur’s attitude to Luttig’s. If we must defeat Donald Trump in November to prevent him from smashing American norms, but the only way to defeat him is to smash those norms ourselves, then … what is the point, exactly?

What is classically liberal conservatism conserving in that case?

Underlying Luttig’s argument is the sense that democracy no longer works as well as it used to. American institutions could safely follow the ethical guidelines by which they’ve traditionally abided so long as the people themselves were virtuous enough not to reward a comically vulgar demagogue with power. That virtue has now been lost. And so some institutional actors—like courts, prosecutors, and Judge Walton—may feel an earnest duty to try to fill the vacuum by confronting the demagogue themselves, even if that means carving out ethical exceptions to do so.

I understand the impulse. Trust me, I do. But putting a thumb on the scale by ignoring traditional norms amounts to institutions admitting that they no longer trust the people whom they allegedly serve to defend the constitutional order themselves. The “pro-democracy” movement that opposes Trump is actually pretty anti-democratic in that respect.

If all of that doesn’t move you, consider how swing voters might be processing all of these examples of ethical rules being broken by Trump’s critics in law enforcement. The more correct the broken clock appears to be, the more tempted some of those voters will be to conclude that it isn’t really broken at all. In an election that may turn on Americans’ judgments of whether Trump or his political enemies are more incompetent and corrupt, every “broken clock” moment gets him a little closer to victory.

So, no, Judge Walton shouldn’t have done the interview.

But I can scold him only so much.

The vacuum of condemnation described by Luttig is real, after all, and predictably most pronounced on the American right. It’s an ineffable disgrace that Trump continues to try to intimidate law enforcement in the light of day, up to and including digs at their children, and endures scarcely a word of meaningful protest from anyone to the right of Liz Cheney.

That’s partly because many have been physically intimidated themselves. When former Trump White House communications director Anthony Scaramucci was asked recently why more Republicans weren’t speaking out against the former president, he answered bluntly: “They probably don’t like death threats.” Being threatened with harm by Trump’s rabid fans is now a fact of American political life and no one with a modicum of influence in the GOP has the nerve to object to it. So Judge Walton opted to fill the void.

It’s also hard to get indignant about his CNN appearance in light of the cynicism with which Trump apologists routinely yet falsely spin every bit of institutional resistance he encounters as a “broken clock” moment. Jonathan Chait had their number in a piece published Wednesday by New York magazine in which he identified disingenuous abuse of the term “lawfare” by figures across the American right:

The advantage of this catchall term is that it allows Trump’s defenders to ignore the specifics of Trump’s misconduct, or at least to analyze it in a highly selective way. There are indeed a couple instances in which Trump has faced legal challenges that are questionable (the attempt to disqualify him from the ballot based on the 14th Amendment) or downright weak (Alvin Bragg’s indictment over hush-money payments to Stormy Daniels). Conservatives tend to focus obsessively on these cases, and “lawfare” is a permission structure that allows them to use these cases to ignore or discredit the others, where Trump’s behavior is impossible to defend.

It is a similar rhetorical strategy to the way Republicans dismissed the entire Russia scandal as “Russiagate” (or, in Trump’s preferred phrasing, “Russia, Russia, Russia”). The Russia scandal consisted of innumerable strands and accusations, some of which (most famously the Steele dossier) did not pan out. But the sweeping frame allowed Trump’s defenders to ignore the voluminous evidence of guilt. No need to defend Trump pardoning the campaign manager who had a Russian intelligence agent as a partner when you can just denounce Russiagate as a hoax.

That’s correct, and it’s as true of anti-anti-Trump conservative partisans as it is of diehard MAGA populists. Devoting oneself to running political interference for the Republican Party, as both groups do, requires relentlessly muddying the waters between genuine examples of Trump’s enemies behaving irresponsibly and examples of them simply holding him to account for his own irresponsible behavior. It’s the same impulse that motivates bad-faith right-wing analogies between Trump’s 2020 coup attempt and the fact that certain random Democrats questioned the results when he won in 2016.

Ask yourself: How often do Trump apologists in right-wing media attempt to draw ethical distinctions between Fani Willis on the one hand and Special Counsel Jack Smith on the other? How commonly do they distinguish the dubious Stormy Daniels prosecution in Manhattan from the formidable case against him in Florida for concealing classified documents? Their goal in refusing to do so is to convince Republican voters to lump together all accusations of misconduct against Trump, no matter how well substantiated, and dismiss them out of hand en masse as part of the same meritless “witch hunt.” That goal has largely been achieved

Go figure that Judge Walton thought desperate measures were needed to try to puncture the information bubble by using CNN to reach more conciliatory Republican viewers about threats being made to judges and their families.

I understand his decision to appear on the network for another reason, though.

Trump gets to threaten people, to preemptively cast doubt on the legitimacy of the election, to tease violent unrest if he’s convicted of a crime, and to promise “retribution” for his enemies if he’s elected, all with political impunity. As a matter of moral and civic duty, Joe Biden and the leaders of his party must be better.

It’s the right thing to do. But emotionally, it is maddening to have to engage in asymmetrical political warfare with Trump and his most goonish, dishonest enablers.

Judges aren’t supposed to indulge their emotions in public discourse, which is why I’m Team Isgur more so than Team Luttig. But as a matter of common humanity, one can’t help but sympathize with Judge Walton emotionally for not remaining similarly passive as Trump stoops to thuggery toward the law that even a mafia don would eschew. When someone makes a habit of physically intimidating others, a rule-of-law stickler might understandably feel compelled to raise a very mild objection to it publicly rather than take it lying down.

That’s what Walton did. Consider it a matter of self-defense, a principle Republicans normally cherish and exalt. If the American right won’t defend the courts from Trump’s intimidation racket, shouldn’t the courts defend themselves?

They’ve been moved to defend their integrity from Trump’s attacks before, remember, although admittedly not in the thick of an election campaign when he was facing dozens of federal criminal charges.

The “broken clock” problem exemplified by Judge Walton’s interview recurs eternally in liberal societies confronted by illiberal threats because it feels foolish and self-defeating to follow norms designed to protect the rights of authoritarian cretins who wouldn’t extend the same courtesy if the roles were reversed. And when said cretins start crying crocodile tears about ethical rigor amid their usual hosannas to a man who doesn’t understand ethics as a concept except as something suckers believe in to justify their own weakness, it’s downright infuriating.

The illiberal faction will always cynically exploit ethical lapses by the liberal establishment they resent and hope to replace to draw a moral equivalence between that system and their own brand of “might makes right” politics. Having to indulge them while they play that game is, as I say, sincerely maddening—even for a federal judge.

But what’s the alternative? If the only way to stop Trump from becoming president and appointing partisan judges is to have judges quasi-campaign against him on CNN, the great war over normalizing Trumpism is already over. We lost.

I think we lost regardless, even if we resolve to slap Reggie Walton on the wrist. And I think he thinks so too: He wouldn’t have agreed to appear on CNN, I assume, if he didn’t think the hour was late in getting American voters to care about politicians using threats as a pressure tactic. The battle against Trump might be won in November, but Trump has never been the problem in all this. The real problem will remain.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.