Readers of colonoscopy age will recall the famous Saturday Night Live sketch from Campaign ‘88 starring Dana Carvey as George H.W. Bush and Jon Lovitz as Michael Dukakis. Carvey babbles inanely through a series of Bush-isms—stay the course, a thousand points of light—at which point a glum Lovitz deadpans, “I can’t believe I’m losing to this guy.”

I thought of it this weekend when I watched the vice president of the United States babble inanely for two minutes on national television about codifying Roe v. Wade without the faintest idea of what that would look like in practice.

My fellow pro-lifers: I can’t believe we’re losing to these guys.

But we are losing, in more ways than one. And Republican leaders know it.

The surest sign that a political party recognizes that it’s losing is when its members start to mutter about “messaging.” We’re now deep into that stage of the right’s post-Roe hangover.

Ideologues always avoid facing the harsh reality that one of their policies is unpopular until they’ve eliminated all other possibilities. Poor “messaging” is an evergreen possibility. The people are with us; all we need to do is market our plan the right way.

The product is great! It’s the branding that’s flawed.

The term “pro-life” is good branding, one would think, and not just because it aligns the right with something everyone favors in the abstract. It’s gotten results, delivering enough GOP victories at the federal level over the past 50 years to have produced a 6-3 Republican-appointed Supreme Court majority and, at long last, the end of Roe. Since 1976, when the GOP first added anti-abortion language to its platform, the party has won as many presidential elections as Democrats have. In 1994, with the pro-life position cemented as right-wing orthodoxy, Republicans gained a majority in the House for the first time in 40 years. As recently as 2018, they controlled both chambers of Congress and the White House.

There’s simply no evidence that the term “pro-life” was costing the GOP elections. And insofar as it’s begun to cost them elections now, I dare say that voters aren’t reacting to the “brand” as much as they are to the fact that Dobbs has revitalized the issue of abortion as a democratic concern. Until 2022, pro-choice voters who otherwise lean right could vote Republican, secure in the knowledge that federal judges would thwart the legislative ambitions of the party’s pro-life majority. Since 2022, that’s no longer the case. Some of those leaners seem to have adjusted accordingly, leaning the other way.

But if you’re a committed opponent of legal abortion, now forced to contend with the fact that your position has become a political liability, it’s easy to retreat into the belief that there may be a “messaging” fix to this problem. According to NBC, that’s what Republicans on Capitol Hill have begun to do.

At a closed-door meeting of Senate Republicans this week, the head of a super PAC closely aligned with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., presented poll results that suggested voters are reacting differently to commonly used terms like “pro-life” and “pro-choice” in the wake of last year’s Supreme Court decision that overturned Roe v. Wade, said several senators who were in the room.

…

“Many voters think [‘pro-life’] means you’re for no exceptions in favor of abortion ever, ever, and ‘pro-choice’ now can mean any number of things. So the conversation was mostly oriented around how voters think of those labels, that they’ve shifted. So if you’re going to talk about the issue, you need to be specific,” [Sen. Josh] Hawley said Thursday.

…

[Sen. Kevin] Cramer, asked what terminology senators should use instead of “pro-life,” said: “I think it’s more of a ‘I’m pro-life, but … .’ Or it’s ‘I care deeply about the mother and the children, and we should always have compassion. But I believe that after 15 weeks where the child can feel pain, they should be protected.’”

One Republican, Sen. Todd Young, described the meeting as having focused on, ahem, “pro-baby policies.”

All of this smacks of a feeble attempt to repackage old wine in new bottles in hopes of misleading skittish swing voters. Republicans are no longer “pro-life,” a term those voters now equate with the sort of unpopular strict abortion bans enacted by red states like Texas, you see. They’re “pro-baby.” It’s different! And so voters might assume that the policies to which it refers must be different too. Even if they really aren’t.

That’s one theory of the “rebrand.” But I wonder if there’s more to it.

The problem with the “old wine in new bottles” interpretation here is that the party and some of its most influential pro-life supporters have quietly begun selling new wine under the pro-life—or pro-baby, if you prefer—label. It’s not just the brand that’s changing, it’s the product itself. And as the GOP’s staunchly pro-life voters come to realize that, there’s a risk that some will balk.

Republicans’ focus on “branding” might be less about swing voters than about anti-abortion stalwarts within their own base, attempting to distract them from the GOP’s substantive shift on the issue by getting them to focus on a cosmetic change instead.

Consider how far the goalposts have already moved from the sort of strict six-week federal abortion ban that Mike Pence favors. Donald Trump called a similar ban that Ron DeSantis signed into law in Florida “too harsh” earlier this year, yet he’s paid no discernible price for it in primary polling. DeSantis himself has hinted that there shouldn’t be a federal ban at all, suggesting that abortion is an issue for the states rather than the federal government. He was scolded for that by America’s most prominent anti-abortion group, Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America—but not because they’re demanding a strict Pence-style federal ban. They’re apparently willing to settle for federal restrictions after 15 weeks of pregnancy. That’s in line with Republican sentiment generally per a recent poll by Echelon Insights, which found 71 percent of GOP voters favor a ban after 17 weeks that includes exceptions for rape, incest, and the life of the mother.

Do you realize what a retreat this is from traditional pro-life dogma?

In 2016, the official Republican Party platform called for a Human Life Amendment to the U.S. Constitution clarifying that unborn children are protected under the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment, a measure that would effectively ban abortion nationwide. Republican politicians have for decades spoken of abortion in the starkest moral terms, some even comparing it to the abomination of slavery. Now here we are in 2023 and the “pro-life” position among party leaders and some influential activists is to pass federal legislation to ban the practice after 15 weeks—which would permit all but 6 percent of abortions.

Even that goes too far for some. Nikki Haley, the lone female candidate in the Republican field, has dismissed a 15-week federal ban out of hand because it would be dead on arrival in Congress. She’s encouraging her party to aim lower and focus on banning late-term abortions and encouraging adoption instead.

The GOP remains strongly “pro-life,” “pro-baby,” or what have you, then, only with respect to blood-red states where strict bans can be imposed without serious political blowback. Nationally, and perhaps soon in purplish states where abortion politics could haunt them at the polls, Republicans seem willing to effectively capitulate to pro-choicers by adopting policies that would permit roughly 95 percent of terminations.

Which, one might argue, is a fine democratic outcome. If that’s where the people want to draw the line, that’s where it should be drawn. And while pro-lifers were doubtless expecting a steeper reduction in dead children in the post-Roe era than a few percentage points, a decrease is a decrease. Just as Nancy Pelosi was willing to risk disaster at the polls in 2010 for the sake of passing Obamacare, so Republicans should be willing to suffer some electoral pain for the sake of saving thousands of babies.

But here we come to the other way in which pro-lifers suddenly seem to be losing. What if thousands of babies aren’t being saved now that Roe is gone?

What if, in fact, more are dying than before?

New data published last week by the Guttmacher Institute suggests more abortions were performed during the first six months of this year than during the first six months of 2020, the last time the organization sampled abortion clinics.

Obamacare survived determined Republican efforts to repeal it, justifying Democrats’ electoral sacrifice on its behalf. If the GOP’s reward for its own sacrifice is having abortions increase then what was the point, exactly?

Altogether, about 511,000 abortions were estimated to have occurred in areas where the procedure was legal in the first six months of 2023, a review of Guttmacher’s data shows, compared with about 465,000 abortions nationwide in a six-month period of 2020.

Abortions rose in nearly every state where the procedure remains legal, but the change was most visible in states bordering those with total abortion bans. Many of these states loosened abortion laws, and providers opened new clinics to serve patients coming from elsewhere. In Illinois, for example, where abortion is legal, abortions rose an estimated 69 percent in 2023 compared with the same period in 2020, to about 45,000 from 26,000.

The happiest spin one can put on those numbers is that the uptick—if there was an uptick—wasn’t entirely driven by the Dobbs ruling.

In fact, the growth in abortions didn’t begin last summer when Roe ended, according to Guttmacher. It started in 2017, reversing a nearly 30-year-long decline, and continued through the first year of the pandemic despite social-distancing protocols that one might assume would have kept some pregnant women out of abortion clinics.

There’s no silver-bullet explanation for the trend. Guttmacher cites states expanding Medicaid coverage of abortion and a Trump administration policy that led some poor women to lose access to contraception as contributing factors, but the rise of so-called “medication abortions” surely played a role too. In 2020, for the first time, more abortions in the U.S. were carried out via medication than by surgery; in 2021, the FDA made permanent a pandemic-era rule authorizing a well-known abortifacient to be prescribed via telemedicine and sent to patients through the mail. (That policy is being challenged in court.) At-home abortions are easier and may seem less objectionable to some women who blanch at the thought of gruesome surgical interventions.

Dobbs has nothing to do with any of that. To the contrary, had the Supreme Court come out the other way in that case, it’s anyone’s guess how many more abortions would have occurred this year than actually did.

But you don’t need to strain hard to see how a backlash to Dobbs might also be contributing to a rising tide in abortion.

As noted in the excerpt, some states where the practice is legal further liberalized their abortion laws following the ruling, whether to meet a surge in demand from out-of-state clientele or to signal defiance of the right’s great cultural victory. That greater access coupled with the mainstreaming of no-frills “medication abortion” may have more than offset the decline in terminations in states with strict bans, leading to a net increase nationally.

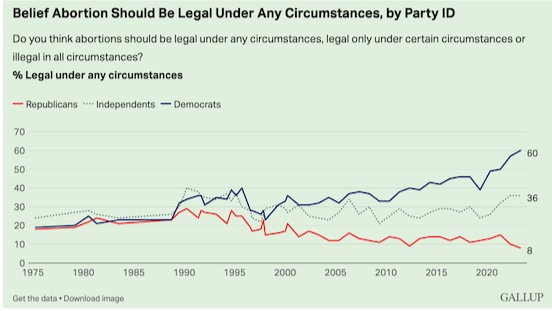

I wonder, too, if widespread public antipathy to the end of Roe hasn’t influenced how some women came to view their own pregnancies. Gallup reported in June that 69 percent of Americans, a record high, now believe abortion should generally be legal during the first trimester. Fifty-two percent say that the practice is morally acceptable, tied for another all-time high. When you drill into the data you find that the shift has been pronounced among Democrats and women:

I don’t mean to suggest that some pregnant woman belatedly decided to abort a child she had intended to keep as an act of protest against Dobbs. What I mean is that the supernova of liberal agitation around the issue after the ruling, and the legislative initiatives that have followed, may have changed some women’s minds about the morality and feasibility of aborting their pregnancies. Tons of media coverage about abortifacients-by-mail and women’s right to “control their own destinies” might have mainstreamed the practice among skeptics in a way that it hadn’t been mainstreamed before. The result: more abortions on balance, even with red states cracking down.

Or not! Pro-lifer Michael New recently published a critique of the Guttmacher data at National Review questioning the group’s methodology. Their numbers aren’t based on an exhaustive survey of abortion clinics, merely a sample to which they apply a statistical model aimed at guesstimating the national total. And the acid test of whether overturning Roe was worth it isn’t what’s happening in blue states, New argues, it’s what’s happening in red states that have taken advantage of the post-Roe regime by circumscribing abortion. More babies are being born there. Legal prohibition, or at least severe restriction, does work. Dobbs did what it was supposed to do. It was worth it.

Sort of. If you think blue states can be persuaded over time to change their minds about abortion and to limit the practice legislatively, then yes, overturning Roe was a worthy policy project. (It was a worthy legal project irrespective of the policy consequences.) And maybe they can be persuaded; again, even by Guttmacher’s measure, abortion declined in the U.S. for almost 30 years before it began increasing again. But if you’re skeptical about liberals ever seeing the light, a post-Dobbs reality in which pro-lifers lose consistently at the polls and abortions remain stubbornly high nationally feels like a Pyrrhic victory for conservatives.

Especially if it produces a Democratic majority in Washington that ends up codifying Roe by statute, whatever that might look like in the tortured mind of Kamala Harris.

In the near-term, I suspect we’re going to see different camps of social conservatives battle over the legacy of Dobbs. One will be what we might call the Michael New faction, longtime pro-life activists who invested heavily over the years politically and emotionally in the project to overturn Roe. This faction won’t easily—or ever—concede that the project was a failure or that it proved to be more trouble than it turned out to be worth.

Another will be hardline pro-lifers who are unhappy that abortions haven’t declined and will demand more draconian measures from the GOP to try to bring about that outcome. If it’s a dire moral issue, as Republicans have often said, then there’s no excuse for not pulling whatever levers of power are available to produce the right moral outcome. Nothing matters relative to that, including the next election. If ending Roe is to mean anything, abortions must—must—decline.

Finally, there’ll be post-liberal populists (some of whom might not even be sincerely pro-life) who are only too happy to cite abortions rising after Dobbs as further evidence of the impotence of the conservative movement. “What has conservatism conserved?” they like to ask. “We ended Roe!” conservatives now reply. To which populists will say: “And what did you get for it? More abortions and more defeats at the polls?” If you want to work your will politically, you don’t tediously fill Supreme Court vacancies over a span of decades. You act. Authoritarianism is the only option.

Meanwhile, amid all of that, Republicans who aren’t very socially conservative and/or who prioritize winning elections will be nudging the rest to accept a wimpy 15-week federal ban and to consider dropping the matter after that.

There’s no avoiding this reckoning unless and until abortions begin to decline meaningfully. The chatter over “branding” is just papering over the dispute.

If you appreciate what we’re doing here at The Dispatch, we have a small favor to ask: Forward this email to someone (or a few someones) in your life who might enjoy getting Boiling Frogs every day. Let them know why you’re a reader, and that they can click “sign up for this newsletter” at the top of the email. For the next few days, the members-only version of Boiling Frogs will be unlocked for all to read.

To do more of the kind of work we want to do, we need more members. And the best way to get more members is word of mouth from the people who know us best. Thanks for your help.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.