Republican support for Medicaid expansion in North Carolina was almost unthinkable a decade ago. Thom Tillis, then the speaker of the state House, guided a bill to passage in 2013 that blocked any future governor from unilaterally expanding Medicaid, an effort he touted during his 2014 U.S. Senate campaign as “fighting against Obamacare.”

But North Carolina Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper signed a Medicaid expansion bill Monday that enjoyed broad and enthusiastic support from the state’s Republican majority: House members even violated parliamentary protocol to give the bill a rare standing ovation as they sent it to the governor’s desk.

While other right-leaning states have expanded Medicaid through ballot initiatives or executive action, North Carolina is the only state to do so with GOP lawmakers leading the way—a sign that after more than a decade fighting Democrats, Republican resistance to Obamacare may be on its last legs.

Medicaid expansion: a primer.

Since Congress created Medicaid in 1965 as a health care safety net for low-income Americans, both the federal government and individual state governments have regularly tinkered with it since both levels have administrative responsibilities. Some states have expanded eligibility for pregnant women, for example, and the federal government temporarily upped its share of the “matching funds” formula as part of a pandemic-era relief law.

But the Medicaid expansion bill signed into law in North Carolina is more than just tinkering.

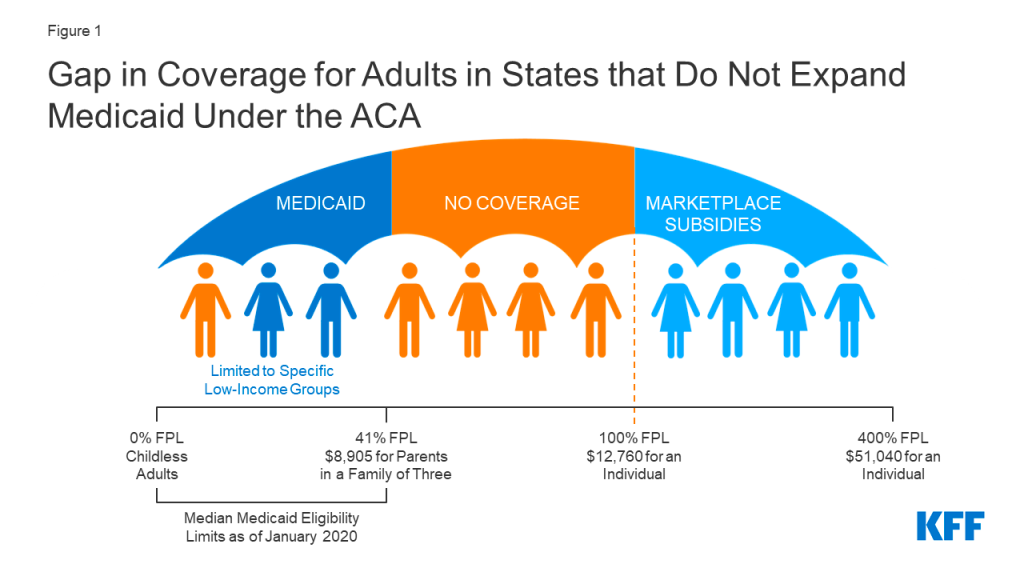

One provision of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded the income range for Medicaid eligibility, from approximately 41 percent of the poverty line to 138 percent. In regular Medicaid, the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) determines how much of states’ Medicaid costs will be covered by the federal government—a rate that varies from state to state based on a number of factors. But the Affordable Care Act’s expanded Medicaid is financed by a set 90 percent/10 percent split between the federal government and the states, and it covers childless working adults, not just those with families.

The law tried to force expansion in all 50 states by threatening to cut off all federal Medicaid funding, but a 2012 Supreme Court decision deemed such a move unduly coercive. The national GOP promised to “repeal and replace” Obamacare, and Republican-led states dug in their heels against the Medicaid expansion provision—hence Tillis’ 2013 legislation.

The architects of the ACA assumed all states would expand Medicaid, but some states’ decisions not to left a “coverage gap,” largely of working-class adults who make too much money to qualify for regular Medicaid but not enough to afford subsidized plans in the bill’s newly created individual market—creating the problem advocates for Medicaid expansion at the state level hoped to solve. North Carolina’s expansion is expected to provide coverage for at least 600,000 people, more than 5 percent of the state’s population—though implementation will be delayed until the General Assembly passes a budget later this year.

“Hundreds of thousands of hard-working North Carolinians, many with two or more jobs, have suffered in the health care coverage gap while a solution sat just out of reach,” Cooper said at Monday’s signing ceremony. “With this law I’m about to sign, many of them will be close enough to grab it.”

The failure of ‘repeal and replace.’

Much conservative opposition to the ACA was based on fundamental disagreements about the government’s role in providing health insurance.

“There was some thought that different ways of doing reform could emerge from opponents of the law that wouldn’t rely so heavily on just straight expansion of an existing very large benefit program,” explained Jim Capretta, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Many of those ideas involved offering tax credits as an inducement to persuade low-income Americans (including those in the coverage gap) to purchase private health insurance.

“But it became clear that the opponents of the Affordable Care Act really were never going to coalesce around anything,” Capretta added. “That was apparent in the 2017 repeal-and-replace effort, which I think is pivotal in this history.”

Under Speaker Paul Ryan, the House passed a “Trumpcare” bill, and Republican leaders even held a celebratory event at the White House—but the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office said the plan would lead to a major increase in the uninsured population, creating political headaches that ultimately doomed the party’s ACA-repeal efforts.

“They tried to slap it together on the fly in the early months of 2017, and they just didn’t have consensus or clear enough thinking or strong enough plans to get it done,” Capretta said.

That failure at the federal level gradually changed the calculus for Medicaid expansion in the states. Republican governors and state legislatures waited for an ACA replacement that never arrived—and turning down the federal funds for expansion began to make less and less sense.

Why North Carolina expanded.

In North Carolina, state Senate leader Phil Berger still insists that “the Affordable Care Act as enacted was and is bad federal policy and has done much to exacerbate problems in healthcare.” But, he writes, “every attempt in Congress and by the courts to reverse the ACA and Medicaid expansion has failed. … It’s not going away, and refusing to accept that reality hurts North Carolinians and the state’s finances.”

Regardless of whether Obamacare was a fiscally responsible choice at the federal level, expansion proponents now argue that question isn’t in state legislators’ purview: They make state policy, and from the state’s perspective, expansion is a fiscal boon.

And North Carolina’s deal got sweeter the longer it held out. Under the American Rescue Plan Act—President Joe Biden’s 2021 COVID relief package—the federal government is offering holdout states a no-strings-attached “signing bonus” by temporarily increasing the regular matching funds rate, resulting in what is essentially a $1.8 billion check to be spent at the North Carolina General Assembly’s discretion. Plus, the state isn’t asking everyday taxpayers to pay for the 10 percent share of the cost of expansion, at least not directly. Instead, a new “assessment” on hospital revenues will cover the cost while also unlocking even more federal money for Medicaid through some gimmicky math. The bill will also support hospitals through the federal Healthcare Access and Stabilization Program (HASP), which House Speaker Tim Moore said Monday would have a “generational impact.”

Reimbursement for Medicaid expansion patients is expected to increase hospital revenues, especially in rural areas. “Even with the new assessment, expansion is a net positive for the hospitals,” Berger wrote.

Another reason Berger changed his mind is that his party has already secured long-sought reforms to the state’s health care system: North Carolina recently “transformed” its Medicaid system from a traditional fee-for-service model to a managed care model designed to stabilize costs for the state and encourage investment in preventive care, making the overall Medicaid population healthier and less expensive to insure.

The expansion legislation also rolled back licensing requirements for some new health care facilities to open in an effort to boost competition—an expression of the GOP’s “traditional interest in more free-market approaches,” according to Niskanen Center policy analyst Robert Orr.

Some conservative analysts, such as the John Locke Foundation’s Donald Bryson, have argued that the Medicaid expansion deal is still a bad idea because it isn’t free-market-friendly enough.

But Berger seems content to keep agitating for “additional supply-side reforms” while not letting the perfect be the enemy of the good.

“Medicaid expansion will not solve all the problems our citizens encounter when they seek care,” he said at Monday’s signing ceremony. “But if we see this as an opportunity to further chip away at archaic rules that prevent our citizens from accessing care, we can enhance real and measurable access to health care here in North Carolina.”

Even Tillis has moderated his views on expansion. “If we have new data, if it provides better access to care, if it provides better outcomes, then look at the data before you and make that decision,” he told a CBS affiliate last year.

Will other states follow?

One way to read the story is that it’s more evidence for a Republican “realignment” in which the party is becoming more attuned to the economic concerns of working-class voters and more friendly to using the government to respond to those concerns.

That may be true in part. But House Republicans at the federal level are proposing steep Medicaid cuts, and the largest remaining non-expansion states are the Republican strongholds of Texas, Florida, and Georgia—and thus far, they haven’t budged. Cooper’s use of the bully pulpit over the years may have helped push state lawmakers to action in a way that GOP governors like Greg Abbot, Ron DeSantis, and Brian Kemp would be less likely to emulate.

But if history is any guide, they’ll get there eventually. After Medicaid was first introduced in 1965, some states held out longer than others—Arizona didn’t get on board until 1982, for example—but the program is now universal.

In North Carolina, Republicans were ready to move on from Democrats—led by Cooper—owning what has become a popular issue. And with the failure of repeal-and-replace, they had little choice but to pull the expansion lever if they wanted more people in the coverage gap to access health insurance—which, in Capretta’s view, is a worthy goal.

“When the ACA was debated, analysts who were concerned about Medicaid covering a sizable share of the population tried to push for alternative policies using tax credits and private insurance that could provide better access to services for lower-income households,” he said. But now, “it is clear that none of those kinds of ideas will ever get advanced by Republicans, and so the only realistic way to make sure this population will get coverage is through Medicaid.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.