AMBLER, Pennsylvania—Committed Democrats in this contested corner of perhaps the most pivotal 2024 battleground state would welcome Vice President Kamala Harris moving to the political center to outflank Donald Trump with persuadable independents and swing voters, fervent as they are to defeat the Republican nominee.

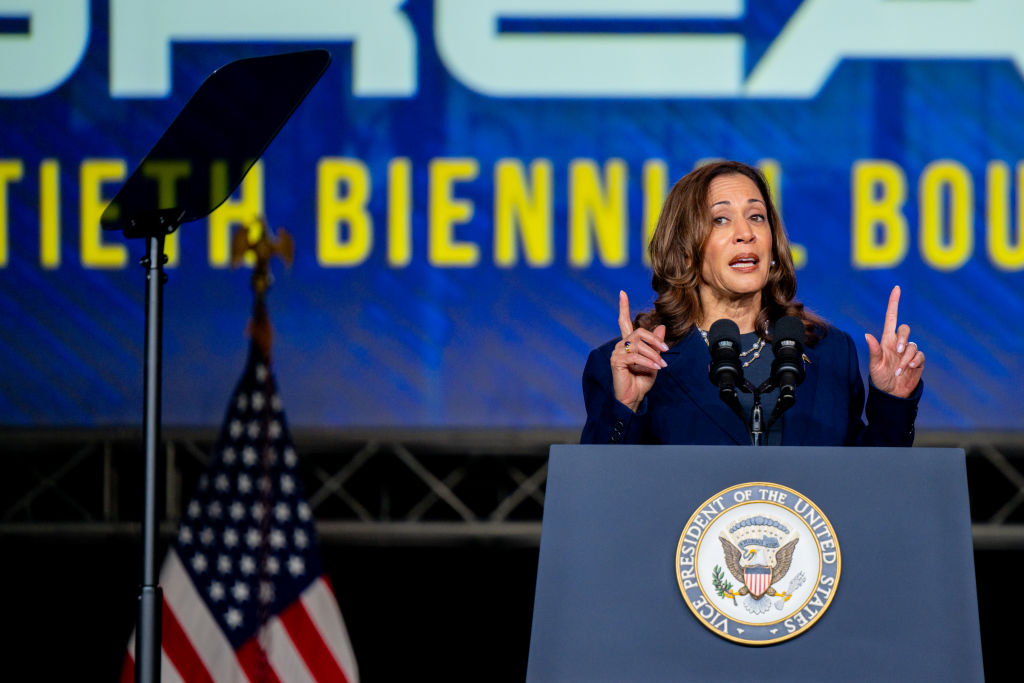

Harris has begun her unexpected White House bid with a reputation for left-wing liberalism, well-earned through outspoken support for a host of progressive priorities during a failed 2020 campaign for the Democratic nomination that included health care, environmental, and immigration issues. Those past positions didn’t bother voters The Dispatch interviewed this week during a Harris campaign rally in suburban Philadelphia hosted by Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro and Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer. They are largely in sync with the party’s liberal base, and thrilled the presumptive Democratic nominee is competitive versus Trump.

But anxiety over the former president’s potential return to the Oval Office is making political pragmatists out of even the most dedicated Democratic partisans. Not only did these voters say Harris has their blessing to moderate on key issues, some said they hope she triangulates, believing the strategy is essential to victory. This latitude to maneuver is a crucial development with ramifications for November, especially as Harris prepares to select a running mate.

“I think she should move to the center a little bit and not be billed as a left-wing—what they’re putting her out to be, a liberal,” Rich Migliore, 72, a retired teacher and attorney who now represents educators in due-process rights cases, said while waiting for Shapiro and Whitmer to take the stage in a packed high school gymnasium “We can’t move backward as a country. We need to move forward.”

Another of the approximately 1,200-plus rallygoers, Michele Cohen, is a middle-aged attorney who described her personal political preferences as once moderate but now “left, left, left”—an evolution she credited to Trump’s rise and putative leadership of the Republican Party since 2015. Cohen also wants Harris to embrace centrism, possibly explained by the fact that she lives in a battleground state where far-left and far-right politicians have a harder time winning.

“I believe in being in the center,” Cohen explained. “That’s the way we actually get things done. So, you move past the rhetoric and actually move to governing.”

Just how much compromising Democrats are willing to do to beat Trump may be put to the test. Harris is set to announce her running mate no later than Tuesday, when she and the Democratic Party’s vice presidential pick are scheduled to appear together in Philadelphia before heading across the country on a multistate campaign swing. Shapiro, a leading contender to get Harris’ nod, is considered too moderate by some Democrats and could disappoint elements of the party’s activist base.

But the charismatic, 51-year-old first term governor—who is Jewish and like Harris is a former state attorney general—is electrifying on the stump and has a proven record of appealing to voters across the aisle. In his winning campaigns for Pennsylvania attorney general, he outpaced first-place presidential candidates Trump (in 2016) and Biden (in 2020) on the ballot. Shapiro could help Harris win Pennsylvania and boost her appeal with persuadable voters even beyond Pennsylvania.

“I think the party will be okay with whatever it takes to defeat Trump, Trumpism, and MAGA,” Democratic voter Scott Green, 67, a retired information technology professional, said. Green was so “depressed” after Biden’s June 27 debate flop he “stopped watching CNN and MSNBC altogether, started watching cartoons,” he added. “Even went so far—I left the country, went to Montreal last week for a few days, to help clear my head.”

Then, after the 81-year-old Biden withdrew from the race on July 21 and put his support behind Harris, “I was like, all-in. And my excitement level and enthusiasm level really went up,” Green said.

Harris, 59, was almost immediately more competitive against Trump, 78, who was widening his lead over Biden nationally and in decisive battleground states. Her quick ascent in public opinion polling has been fueled by, among other factors, Democratic enthusiasm and her relative youth. Voters of various stripes who are dissatisfied with Trump but had abandoned Biden because they viewed him as too old and infirm have been giving Harris a fresh look.

That fresh look, however, stands to reveal (or remind voters of) positions on politically charged issues the vice president has previously espoused that could frustrate her campaign against Trump. The risk is particularly acute in seven swing states: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Biden swept all those except North Carolina in 2020—but won them by the smallest of margins.

In the preceding campaign for the Democratic nomination that year, Harris staked out several positions that seemed designed to take votes away from Sen. Bernie Sanders, a Vermont independent and avowed socialist who was the frontrunner in that race until Biden won the South Carolina primary. As pointed out in recent reporting from the New York Times, Harris supported establishing a quasi-government-run health care system; flirted with radically restructuring the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency; and backed a federal ban on fracking—a jobs-rich form of domestic energy production.

Harris has backed or signaled openness to other progressive policies that could foster opposition from all-important persuadable independent voters and disaffected Republicans. It’s why the Democratic voters we spoke with here in Montgomery County, a Philadelphia “collar county” along the city’s western edge and crucial suburban micro-battleground, are giving Harris permission to tack center on major issues. Only maintaining strong support for abortion rights appears sacrosanct.

“I feel like I [could] give a lot of leeway except for abortion, we need to bring back freedom for abortion,” said Jane Curtis, a retired teacher.

No danger there. Proposing to enact federal protections for abortion rights is a centerpiece of Harris’ campaign.But she’s showing flexibility on other issues. A Harris campaign official confirmed to The Dispatch that the vice president “does not support a fracking ban.” The official also rejected Republican claims that Harris is hostile to the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. Indeed, the vice president is proposing to increase funding for a wide array of border security activities.

Granted, Harris’ change of heart on some issues isn’t new. By accepting Biden’s invitation to serve as vice president, she adopted his positions, largely more centrist than her own. But as she charts her own path now, questions about her policy choices are naturally arising. Would President Harris’ foreign policy, including her approach to Israel and the Palestinians, differ from President Biden’s? Domestically, would Harris address health care policy differently? (On that issue, specifically, Harris isn’t talking and the campaign declined to comment.)

When Biden was still limping along as the Democratic nominee, the party’s winning 2020 coalition appeared increasingly fragile. Israel’s war in Gaza to extinguish the threat posed by Hamas was one such political landmine for the Democratic Party; immigration and border security was another. But Democrats expect Harris will be given more leeway to navigate these thorny issues, in part because of the hope she is generating that Trump is beatable.

“I think there are some parts of the Democratic Party, they’re never going to be satisfied with the candidate, whether it’s about the Israel-Palestine issue, or Medicare for all,” said Eyram Gbeddy, 20-year-old Harris campaign volunteer who has spent the summer interning in Harrisburg, the Pennsylvania capital, and is headed to Georgetown Law School in Washington this fall.

“Those are all very important things,” Gbeddy added. “But I don’t think any of that matters if you can’t win.”

Grayson Logue contributed to this report.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.