Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

“In those days nobody knew that he was a boy who belonged to a story. In those days he did not know it himself.” So reflects Wendell Berry in his new novel, Marce Catlett: The Force of a Story.

What does it mean to belong to a story? And what does it mean to belong to a place or a time—attributes in which all people and their stories must be anchored? These are existential human questions, made more pressing and difficult by the unsettled modern American way of life. For too many now, there is no belonging—anywhere, whether physically or spiritually. And with the increased trend of remote working, which has only intensified since the pandemic, people are more isolated than ever in their everyday lives, and less aware of belonging to any meaningful story. Technology of various sorts has made this possible; technology brought us here. But what does this kind of life do to our spirits, our souls? And what does it do to our view of work?

For more than 60 years, Berry, who recently turned 91, has been writing essays, book-length manifestos, and poems about the rootlessness that is the plight of American modernity. People go away from their hometown to college, then move elsewhere for a job, and keep moving time and again their entire working lives. What does this trend do to smaller communities, where farming used to be the way of life, when children who grow up in these communities can’t wait to get away—and then never come back? This phenomenon, Berry has noted in such books as The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture (1977), goes hand-in-hand with lack of cultural regard for the work of farmers in America, a phenomenon now well over a century old. Most people would acknowledge the significance of farmers’ work in growing our food, yet these same people would not wish for such a life for themselves or their children. Technological innovations in both agriculture and the broader American life play a crucial role in this depressing tale, too—and affect us all.

In addition to his other, more direct reflections on these topics, Berry, a farmer himself, has also been reflecting on them with deeply personal care in his novels and stories, set in the fictional town of Port William, Kentucky. A newcomer to Berry could certainly pick up Marce Catlett and enjoy it, but the enjoyment would be deeper for those aware of the previous stories to which this new one adds. Behold, a bloodied man is running through the streets of Port William, a band of others in hot pursuit. Unexpectedly, he runs into the house of a widow and her 5-year-old son. The year is 1888, and Mat Feltner will remember for the rest of his life how his mother tenderly treated the wounds of this hurt man, a stranger to her and subject of Berry’s short story “The Hurt Man.”

Now consider the opening scene of Marce Catlett. Two tobacco farmers from Port William travel one early morning to Louisville for an auction where the fruit of their labor, their entire tobacco crop for the year, is to be sold. The year is 1906, and James B. Duke’s American Tobacco Company has achieved a monopoly. Duke’s representative buys up the tobacco crop at a record-low price, leaving the farmers with no profit at all. The work of an entire year—gone. Devastated, the two farmers travel home in silence. The name of one of them is Marce Catlett. He is going home to his wife and two sons, Andrew and Wheeler.

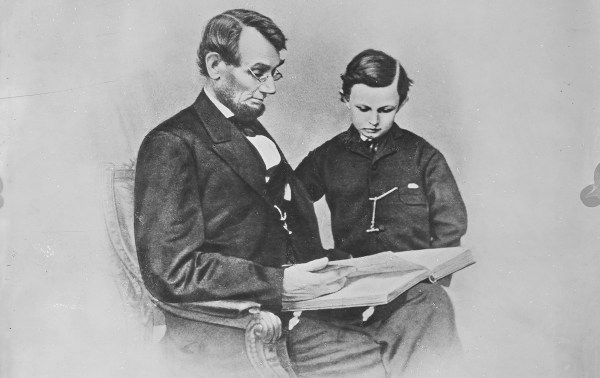

Christmas, 1943: A 9-year-old boy, Andy Catlett, travels alone to spend the holiday with his two sets of grandparents in Port William—the Feltners and the Catletts. The boy who so long ago observed his mother caring for the hurt man is now a grandfather—for little boys have this habit of growing up, even growing old. Beside him is the heartbroken man whose tobacco harvest of 1906 was effectively stolen from him by a system that did not value the work of farmers. He too is now a grandfather. Both live where they were born and where they will die. And the young Andy Catlett is the son of Marce’s son, Wheeler, and Mat Feltner’s daughter, Bess. He is named, of course, for Andrew, Marce’s other son. This is the setting for Andy Catlett (2007), the last full-length novel Berry published before this new one.

Fast-forward 82 years from Andy Catlett, and you have Marce Catlett. It is 2025, and the very elderly Andy Catlett is thinking back over his life. “Like Wheeler his father, Andy Catlett has remembered the story as an event central to his life, though it happened nearly thirty years before he was born.” The story in question? That tobacco sale debacle from 1906.

That is the story to which Berry is referring, first and foremost, in the second half of this novel’s title—“The Force of a Story.” The story has a binding force; it roots people in place and also in relationships. It joins the generations of Marce, his son Wheeler, and his grandson Andy. “The story and the love borne in it, passing down, has held them together like a living root of the same tree, and like a tuned string, across a hundred and eighteen years and five generations,” Berry writes. “But from the year of our Lord 2025, looking back, Andy sees how breakable, how threatened, how perilously stretched across departures and returns that vital strand has always been.” The stories, after all, are all part of family tradition, oral lore handed down from generation to generation. Those who have no deep roots and inter-generational relationships cannot have such stories.

Andy, whose own son is absent from this novel, certainly knows much about the breakable and threatened nature of human lives and bodies. But threatened by what? Longtime Berry readers would know Andy from The Remembering (1976), where he struggles to adjust to life after the loss of his right hand to a corn picker. His entire life, indeed, Andy has been fighting against modernity—and quite possibly losing. This is significant: Berry himself has previously admitted that Andy is the character whom he effectively based on himself. He has never lost his own right hand, yet he too has felt the cost of technology on his life as a farmer and writer. This technology, he is convinced, has been stealing beauty from both of these realms—farming and writing. Modern farmers, using modern equipment, might be hard-pressed to look at the fruit of the labor of their hands as Marce did, seeing something in it that is more akin to a masterful work of art than just a product for sale. And a writer typing on a computer in a secluded room would never know the joy and beauty of putting pen to notepad by the natural light of the morning sun, rising above the farm right outside the window.

What do we take from this melancholy reflection from the last man standing (author and protagonist both), reflecting on a way of life that is gone? I have never been a farmer and cannot even keep houseplants alive. Besides, as Berry’s novels show, the farming lifestyle, even at its best, has never been easy. So why do I keep reading Berry? Because in both his ideas and his writing, I see a soul craving what is so essential for human flourishing: beauty. For it is not only the slower-paced traditional life of small farming towns that the modern industrialized and mechanized trends are driving to extinction. Under threat also is the possibility of beauty, true and genuine delight, in every aspect of our lives, including our work.

At one point in the novel, describing Andy’s memories of working on the tobacco harvest, Berry reflects: “Beauty was the goal—beauty and the satisfaction it gave.” For Marce as well, at the beginning, it wasn’t just the sting of lost profits that caused the greatest pain, but the implied disregard of the beauty of his work. And there was the fear, of course, of losing the place where he and his generational stories were rooted. Can any of us still find such beauty of work done well, whatever it may be, today? Can we find out to which stories, hopefully beautiful ones, we ourselves belong? And can we find beauty in the marriage of both work and family in a society that increasingly pushes us to privilege profit over people? In an America where 47 percent of adults under 50 say they are unlikely to have children—thus opting out of continuing generational stories—these are not easy questions. But still they are worth pursuing.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.