Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

I open X. Since it’s autumn, much of the feed concerns college football. But I also encounter a stream of Lord of the Rings-themed memes, artwork, quotes, and other Tolkien nuggets. And while there are millions of Tolkien fans among both men and women, it does seem as though young men in particular pilot these accounts, talk Tolkien on their podcasts, get lost in chatter of lore and yore. This begs some questions: Why is Tolkien, years after his death, so enduring? And why does he resonate with men in particular?

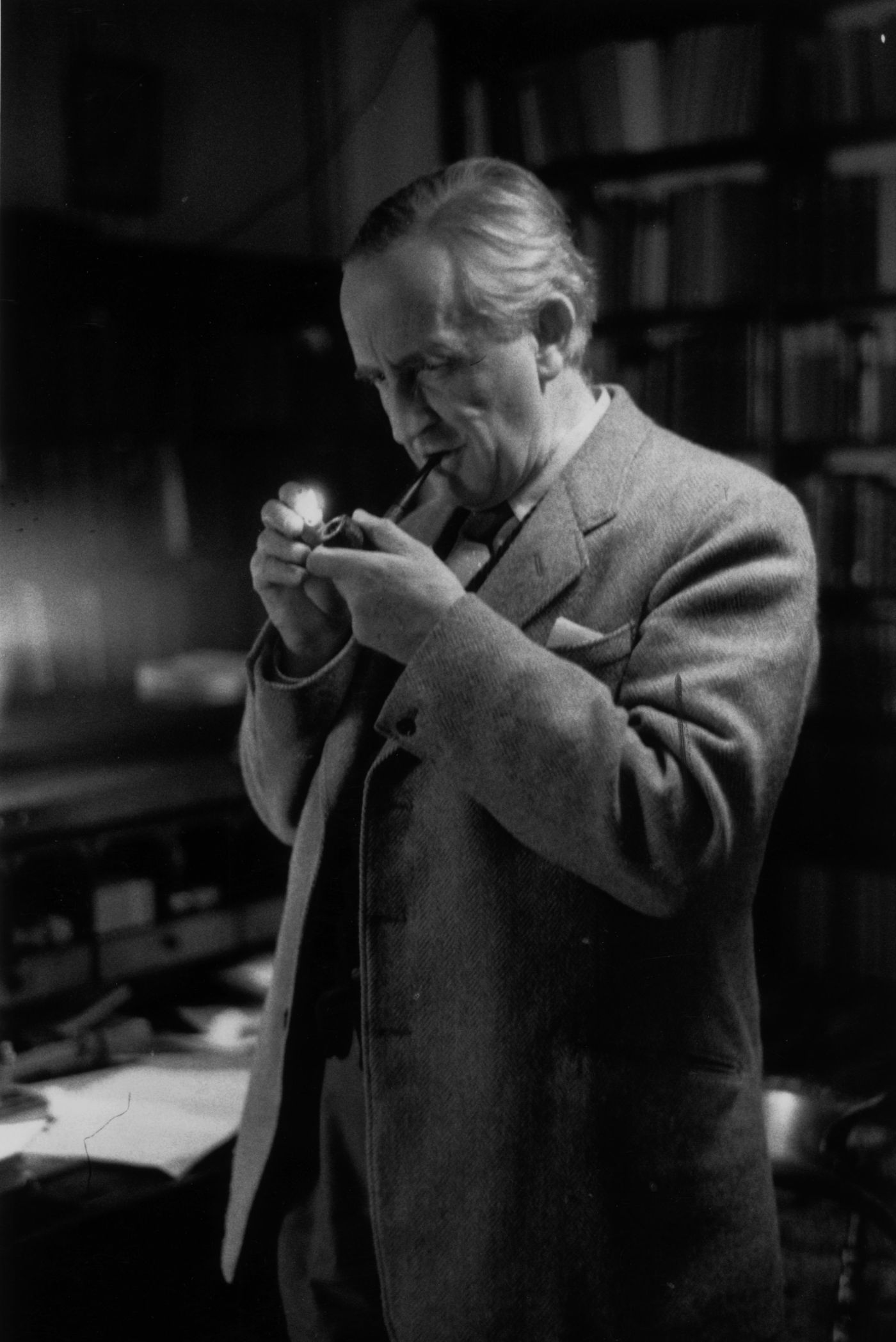

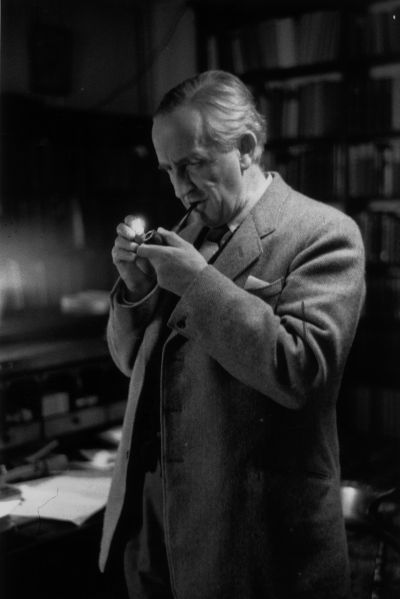

Just a century ago, the young Oxford scholar and veteran of the Great War known as J.R.R. Tolkien was still years from penning the first few words of his celebrated adventure story: “In a hole in the ground, there lived a hobbit.” A philologist by training, Tolkien spent a decade writing the three-part novel The Lord of the Rings, while a certain colleague of his managed to churn out a celebrated children’s series about a magical wardrobe and a beautiful lion in just half the time. Both Tolkien and his friend C.S. Lewis remain imprinted in both Christian and secular imaginations for their fictional work: Greta Gerwig is filming a Chronicles of Narnia Netflix miniseries as Amazon continues to hack away at The Rings of Power, loosely based on the appendices of The Lord of the Rings. (I have my opinions about Jeff Bezos’ “love” for Middle-earth but will spare you a diatribe.)

But Tolkien’s fantasy epic still claims the mantle of, by some measures, the best novel of the 20th century. Something about that work, and something about him, keeps fans, and men in particular, coming back for more.

Tolkien’s mythical universe, meticulously constructed and complete with tailored languages, geography, and a complex history, has created an entire field of scholarship. People devote their writing lives to understanding him and his work. One of these figures is Holly Ordway, a professor at the Word on Fire Institute and author of Tolkien’s Modern Reading and Tolkien’s Faith. Ordway grew up an atheist but later converted to Christianity, noting that Tolkien’s visionary fiction helped this happen. As Ordway writes: “I can attest to the profound impact that Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings had on me; long before I seriously considered the claims of Christianity, I was strangely compelled by his vision of a world that was beautiful and meaningful.”

Today, Ordway writes a lot about what she calls “imaginative apologetics,” a branch of scholarship that recognizes that, while winning people to the Christian faith through pure reason and argument has its place, subtler means shouldn’t be discounted. What about persuading through beauty? Through inspiring characters? Through story? When Ordway encountered two of the last century’s most creative fantasists, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, she was swayed toward faith. Why? Argument alone wasn’t enough; she needed meaning. Christianity was sensible to her only after its truths were imbued deftly in stories, which, as humans, is how we tend to comprehend reality in the first place.

Everything and everyone in Tolkien’s world matters. This is showcased by Tolkien’s dense historical epic The Silmarillion, which traces, in great detail, Middle-earth’s creation and its multi-member cast of heroes and villains, as well as by the fact that Tolkien invented entire languages simply for The Lord of the Rings. The man was also a master at the powers of emotive description. One such example is when Sam sees a hint of the stars through the polluted clouds of Mordor in The Return of the King:

Far above the Ephel Duath in the West the night-sky was still dim and pale. There, peering among the cloud-wrack above a dark tor high up in the mountains, Sam saw a white star twinkle for a while. The beauty of it smote his heart, as he looked up out of the forsaken land, and hope returned to him. For like a shaft, clear and cold, the thought pierced him that in the end the Shadow was only a small and passing thing: there was light and high beauty for ever beyond its reach.

No wonder C.S. Lewis said of Tolkien’s work, “Here are beauties which pierce like swords or burn like cold iron. Here is a book which will break your heart.”

Tolkien’s work is also full of heroic feats, often accomplished by those we might least expect. Though populated with more stereotypical heroes like Aragorn, both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings have hobbits as their central protagonists: It’s Frodo and Sam who carry the Ring of Power into Mordor, and it’s Bilbo who is chosen as the thief to steal back the Arkenstone from the dragon Smaug. Tolkien seemed to believe that the small but stout heart of the hobbit could change the course of history.

Both Tolkien’s cosmic vision of Middle-earth and the many genuine heroes that populate his work likely make for an attractive combination in the eyes of many a meaning-starved young man. We might even wonder if the recent trend of men converting to Catholicism is due to something we also find in Tolkien: the triumph of good over evil, the overflowing beauty of the natural order, and an ultimately meaningful cosmos. I’m an evangelical myself, but understand why so many men my age are flocking to a more organized and historically rich form of the faith: We want structure. We want liturgy. We also want something of a challenge—a faith that refuses to bend to the whims of secular modernity. We want older and better men, including the saints of old (and perhaps even Gandalf!) to call us further up and further in.

As I wrote for The Dispatch a few months ago, boys don’t just automatically become good men in a vacuum; they need role models. Manhood must be carefully nurtured. In the words of author and counselor John Eldredge, masculinity “is bestowed.” Cultural critic and social psychologist Rob Henderson also discussed this idea in a recent article for the Boston Globe, writing:

Mature masculinity is artificially induced through culture. Mature men do not naturally emerge like butterflies from boyish cocoons. Rather, they must be carefully encouraged, nurtured, counseled, and prodded into taking the actions necessary to achieve mature manhood.

Henderson observes that the stereotype of men as aggressive and exploitative beasts is fundamentally wrong. There are men like that, of course. But today we see far more men who struggle with the opposite problem. They are passive, lazy, go-with-the-flow types who would rather stay inside and scroll than seek adventure and take risks. They are not violent. They belong to violence’s dastardly alter ego, which is indifference.

Hobbits are domestic people. As I noted earlier, this means they aren’t likely candidates for heroic feats. They don’t usually go for adventure. That’s what we’re told in The Hobbit, Tolkien’s enchanting prelude to The Lord of the Rings: Bilbo Baggins doesn’t even want local visitors, much less strange ones from faraway lands. It takes the encouragement of Gandalf the wizard to get Bilbo away from his books and his armchair and to travel to a dragon’s lair. It takes a mentor. Gandalf believes that hobbits, despite being small, show remarkable courage just when it matters the most, and we see this confidence in the halflings play out in both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, in which Gandalf entrusts young Frodo Baggins (aided by his friend Sam) with the task of carrying the one Ring of Power into the throes of Mordor. The only person who can withstand the ring’s temptations while making a perilous trek is someone little—someone with a humble heart and whom enemies will least expect to invade their dangerous lands. Tolkien’s books, then, are strange tales when we hold them up against modern values, which include making money, creating a “personal brand,” and seeking power and control.

Adventure. Purpose. Friendship. Fighting a good fight. The friendship and brotherhood that Tolkien portrays so beautifully in The Lord of the Rings is core to what so many modern men are lacking. That, I submit, is among the reasons Tolkien remains indispensable.

I realize that it’s easy to romanticize the idea of “seeking adventure” and fighting dragons and orcs. Not every guy has the impulse to take up a sword and defend the damsel in distress, at least not in the way it might look like in Tolkien’s mythos. But the hunger for something is definitely there. Just something besides this daily screen-filled tedium. Give me something besides TikTok reels and college football highlights. Although most men won’t go off and fight in a war, and although their physical strength isn’t as valued as it used to be, men still want something to do and something to fight for. Sadly, though, the cultural narrative tends to cite men as problems to be solved, not as potential solutions to any larger problem. In 2023, the West Australian ran a now infamous cover story showing a young, harmless-looking boy with the title “How We STOP this Kid Becoming a Monster.” And then you get op-eds from the New York Times like “Toxic Masculinity Is Now Petulant Vulnerability,” which argues that even vulnerability in men often hides a desire to dominate. These pieces both assume that men are problematic. But the latter goes further, implying that, even when men attempt to reform, they’re still rotten at the core.

The narrative of toxic masculinity is based on real concerns. Many men, today and throughout history, have chosen to manipulate and control rather than grow into someone who loves and cares for others. The trend reaches back to the book of Genesis, when the serpent tempted Eve with the forbidden fruit and Adam, instead of intervening, let it all happen. (This is not to mention the countless biblical stories where men have murdered and raped.) Today, though, our cultural story is that men are no longer needed—and that there’s nothing in this world they should love or protect in the first place.

Tolkien’s story is the complete opposite. For all its swords, shields, and kingly returns, The Lord of the Rings is finally a story about love—love for one’s friends, love for one’s home, and love for the ultimate good that will win out in the end. Love is at the center of the story and drives every heroic feat. And while it depends on the simple strength of Frodo and Sam, a strange providence plays a big part in finally bringing the Ring to destruction. For those unfamiliar, a spoiler alert: Just as Frodo is about to destroy the Ring in the fires of Mount Doom, he decides to take it for himself—only for Gollum, a wretch who kept the Ring for 500 years, to bite off Frodo’s finger and accidentally fall into the fire.

One of the most interesting aspects of The Lord of the Rings, then, is the fact that Frodo Baggins fails. This doesn’t mean that his heroic actions up until that point are moot—indeed, he is still known as a hero. Rather, it shows that even when men stumble and fail, we can trust that our actions are still woven into a grand story. Frodo also doesn’t go to Mordor alone; Sam, who Tolkien once called the true hero of the tale, carried the Ring-bearer when it mattered the most. Sam’s own heroism, then, shows us that trying to go it alone tends to hurt us in the long run. What we do matters—but who we do it with also matters.

Will there be another J.R.R. Tolkien in our own generation? I don’t think anyone can replace the original, and I don’t think anyone should necessarily try. We need new storytellers like Tolkien and Lewis, but they will have to grapple anew with how to communicate with a new generation. However, people everywhere can still drink from a well of wonder and wisdom from Tolkien’s classic novel. Men today may not need to fight Sauron or destroy magic rings, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t a real battle that contemporary men are called to. Evil like abuse, manipulation, greed, and moral indifference to the suffering of others is all too pervasive in our world, and there are posts open everywhere that good men need to fill. Far too many of us are sitting back, making podcasts, becoming “content creators,” and opting for a sedentary life, both morally and physically, instead of engaging wholeheartedly in the arena. The world needs us. Men, your churches need you in the pews. Your families need you in the living room, playing in pillow forts and drawing with crayons with your kids. You’re needed at the construction site, the front lines of combat, the corporate office, and the local town forums. Your friends need your wisdom, kindness, and encouragement—just like you need theirs.

I love the virtuous models we have in powerful figures like Gandalf, Aragorn, and Legolas in The Lord of the Rings. I also love the example of the simple hobbit, who is perhaps a bit more relatable to us ordinary humans. For Frodo and Sam, as they trudged toward their goal in the ashy terrain of Mordor, the task was simple—and maybe it’s the simplicity of the quest that attracts men the most. Our world has become so complex that we don’t even know what we’re here for. For now, start simple. Put one foot in front of the other. Keep going. Get out of bed and show up.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.