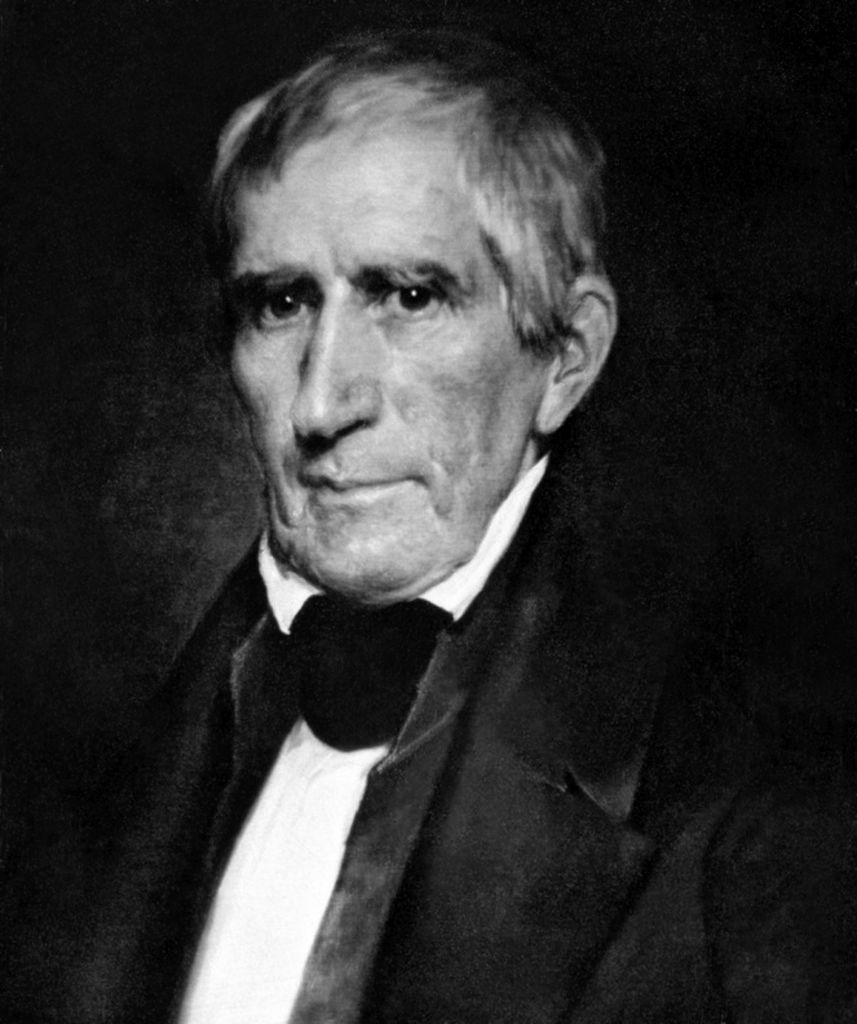

Poor old William Henry Harrison: He’s seldom remembered, and when he is, it’s for dropping dead.

But at least he gets to live on as the answer to a trivia question. Yes, Harrison holds the record for the shortest presidency at just 31 days. No, it wasn’t because he talked too long at his inauguration without wearing a coat. (His doctors probably accidentally killed him when he caught a bug a couple of weeks later, part of the long tradition of presidential iatrogenesis.)

But we should also remember Harrison and the election of 1840 for what they can teach us about how the two-party system works, and doesn't.

Harrison was the first of only two Whigs ever elected to the presidency, and the second was a lot like him. Zachary Taylor, who won in 1848, was also a war hero who also died in office, but made it a whole 16 months—albeit meeting an end even more undignified than Harrison’s. Taylor and Harrison may have been alike in many ways as candidates, but not by imitation of each other—rather, by imitation of their rival party.

The same history teacher who told you about Harrison’s missing overcoat probably told you about the Jacksonian Revolution and the democratization of American politics. That’s why Andrew Jackson was an idol of the Democratic Party until about 20 years ago, when his enthusiasm for slavery and treacherous and cruel treatment of tribal nations became too much to bear. The party of Barack Obama couldn’t also be the party of Old Hickory. Jackson got cashed in.

Republicans, though, were very happy to take Jackson off their hands. And it makes sense. The party of the South and Appalachia, the party of anti-elite sentiment, the party of the working class—the “farmers, mechanics, and laborers” of Jackson’s day—and the party most disdainful of special protections for demographic minorities makes a much better home for the seventh president than today’s ethnically diverse, urban, college-educated, increasingly affluent Democrats.

While Jackson and Trump are as different in backstory as any two presidents could be—Jackson the self-made child of poverty who achieved greatness through self-denial and hard work, Trump … not so much—they shared in common more than a resentment of other elites.

Jackson was one of America’s first real celebrities. His victory over the British at New Orleans in 1815 had been a defining story for citizens of the young nation. We had lost the War of 1812, but he had won the battle that would keep the British from coming back. Around the same time, the printing industry was going through a technological revolution. That meant that color lithographs could be made available for the first time for families of modest means, and a favorite was a patriotic print of Jackson. Not exactly The Apprentice, but certainly mass media appeal.

But long before the MAGA-era Republicans started imitating him, it was the Whigs of Jackson’s own time.

In the 1810s, there was really only one party. The Federalists of the early republic had melted away after John Adams’ 1800 defeat, replaced by rival factions within Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party. By 1828, though, the warring groups split entirely. On one side were Jackson and the Democrats, on the other were the National Republicans, the members who were more conservative, northern, and less tolerant of slavery.

Whatever the followers of Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams called themselves, though, their party would have been more commonly known by a name that accurately described who they were: The Anti-Jacksonians. When Jackson routed the incumbent Adams in the 1828 rematch of their blood feud from four years earlier and thrashed Clay in 1832, the conservatives had to take some drastic measures. Plus, with Jackson a lame duck, a rebranding was in order.

What arose was the Whig Party, or, more accurately, several Whig parties. The party sprang up out of the 1834 midterms in opposition to Jacksonianism, including his membership in the Freemasons. It was a hodgepodge of a coalition, as was evidenced by the nomination of no fewer than four presidential candidates to face Vice President Martin Van Buren in 1836.

Southern Whigs put up two different states’ rights candidates, while Massachusetts Sen. Daniel Webster was the favorite in the North. And from the border states and the West came Harrison.

A son of the Virginia planter elite, Harrison had gone west to the post-Revolutionary War frontier when he, a second son, was left out of his father’s estate. What he found was a gift for military leadership, glory, and new status in what was soon to be the state of Ohio. By the time war approached with Britain again, Harrison had already served in Congress and for a time as the governor of the Indiana Territory.

Harrison was the hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe that helped push the United States into the war, and went on to be the author, along with Adm. Oliver Perry, of the greatest U.S. victory—other than New Orleans, of course—in a daring attack on British and Indian forces in Canada at the Battle of the Thames.

That legendary career plus his East Coast connections and prior government service might have made Harrison a political leader in any case, but 20 years later to a party desperate to counteract Jackson’s grip on the public imagination, Harrison would have been the obvious choice in 1838. Indeed, when the Whigs gave it another go in 1840, they united behind Tippecanoe, but only after a fashion.

When the Whigs held their first convention to pick a nominee for the upcoming election, Clay was the obvious choice. He was the most famous politician in the nation after Jackson, and was widely acknowledged by friends and foes alike as serious, sagacious, experienced, and thoughtful. But the delegates didn’t want him. Who they wanted was an ersatz Jackson of their own, and so they got him—even if Harrison was seen as a lightweight by party leaders.

Might Clay have beaten Van Buren that year? Old Kinderhook was widely blamed for bungling a financial panic and subsequent economic malaise and, a fusty old Dutchman from New York, he was in no position to keep Jackson’s coalition together. But the world will never know because the Whigs, ahem, turned the page on their origins as the Anti-Jacksonians and became Jacksonian Lite.

Which, of course, brings us to Kamala Harris, who is now having a great deal of fun attacking Trump for the things that Trump used to attack her and President Joe Biden for doing: ducking debates, avoiding interviews, being too old for the presidency, etc. She’s campaigning with conservative Republicans and promising a “lethal” military under her administration.

Trump, meanwhile, is campaigning in Democratic strongholds and trying to position himself as the candidate of labor unions, not big business. He’s campaigning with famous former Democrats.

As Seth Masket persuasively argued at The Dispatch this week, the parties are indeed changing lanes in response to and in pursuit of new coalitions. Where the voters go, the parties will follow. And while it may not be exactly strategic, it is certainly tactical, particularly the kind of mimicry that we saw from the Whigs and Harrison in 1840. Realignments may come from the ground up, but they are completed from the top down.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.