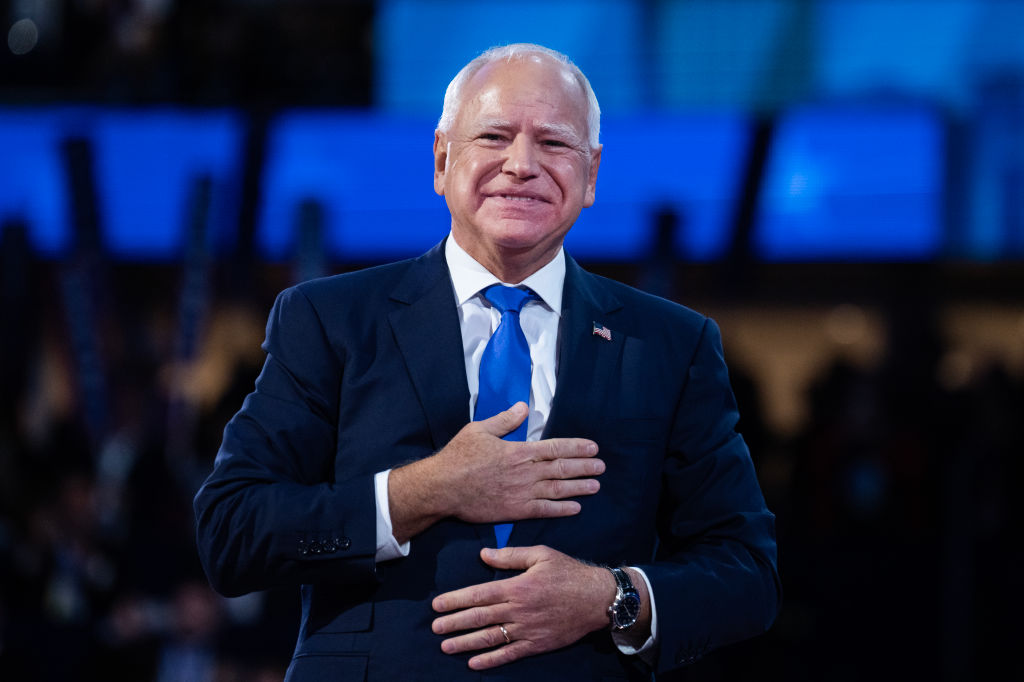

When Tim Walz was tapped to be Kamala Harris’ running mate, some on the left described his selection as an effort to unify Democrats. Walz has certainly tried to play to this reputation on the trail, and now he’s pitching American voters as a whole on a return to a less divisive politics. But unity is easier said than done.

In a speech in Rochester, Pennsylvania, on Sunday, Walz reminded his audience of a time when friends and family could come together for Thanksgiving and “not complain about politics the whole time.” What was different then? Walz went on:

You shared a commitment to democracy, a commitment to personal freedoms

…

We don’t call each other names. We don’t do it. And we don’t use the least fortunate amongst us as punchlines for our jokes because they’re our neighbors. They’re our neighbors.

He repeated his point about neighborliness Wednesday night during his speech at the Democratic National Convention:

Growing up in a small town like that, you learn to take care of each other. That family down the road—they may not think like you do, they may not pray like you do, they may not love like you do, but they’re your neighbors. And you look out for them, and they look out for you. Everybody belongs.

Turning down the temperature of politics and envisioning a greater sense of national solidarity is a welcome development in a time of ever-increasing polarization. Nice is nice—in theory at least. But forging shared commitments and fostering true neighborliness in politics is far harder than Walz and other Democrats let on. They themselves have made it harder in the past.

Take the first shared commitment Walz brought up in Rochester. He’s certainly right to imply how lamentable it is—to put it mildly—that the two-thirds of Republicans who believe the 2020 election was stolen don’t seem especially committed to democracy. But it’s not the case that Americans were always deferential to the democratic process before 2020.

That includes Democrats. Stacey Abrams spent years denying her 2018 gubernatorial loss in Georgia, even claiming on more than one occasion that she “won” the election. That same year, Hillary Clinton looked back at her 2016 loss and claimed that people who voted for Donald Trump did so because they “didn’t like black people getting rights” or women “getting jobs.” Attributing an electoral defeat to bigotry doesn’t exactly scream “commitment to democracy.”

To be clear, Walz’s sentiment—that a shared commitment to democracy is crucial to our body politic—is correct. And he’s certainly not responsible for poor past statements by members of his party. And yes, Trump’s election denialism is considerably more concerning. But Walz is imagining a unified past that was never really so. Political ambition has for quite some time found a way to add caveats and loopholes to our “shared commitment to democracy.”

There’s a similar problem with Walz’s comments about a past “commitment to personal freedoms.” It’s fair to conclude Walz is referring to abortion and reproductive rights, both because the issues have been a linchpin of the Harris-Walz campaign and because he brought them up in Rochester and at the DNC. But here again, past unity has proved illusory. Roe v. Wade began an era of increased polarization by removing the issue from the democratic process. Abortion has been consistently divisive in the ensuing decades, even pre-Dobbs, without any sort of national shared commitment in sight. And even more, divisions over abortion show a second problem with Walz’s pitch for unity: that his appeal to neighborliness rings hollow.

At their best, reasonable people of goodwill and sound mind can recognize the tension at the heart of the abortion debate, between a compelling desire to protect unborn children on one hand, and a compelling recognition of pregnancy’s physical tolls and the way it’s been used to limit the agency of women on the other (among other compelling reasons). A genuine attempt at unity, an earnest respect for political neighbors, would reckon with that tension; Walz elides it. “When Republicans use [the word ‘freedom’], they mean that the government should be free to invade your doctor’s office,” he said at the DNC. For Walz (and virtually all Democrats) people oppose abortion only to oppose personal freedom. Given that wholesale rejection of even a shred of validity of the pro-life view, it’s not surprising that pro-life Democrats are essentially extinct.

Walz has similarly gone hard after Republicans for their supposed opposition to IVF. “Mind your own damn business,” he said at the DNC. This framing downplays that some of the most conservative senators have sponsored legislation to protect the practice. But more importantly, it shows another example of Walz choosing demonization over unitive neighborliness. (To say nothing of his truth problem.)

Opponents of IVF constitute a considerable minority of the public—only 8 percent of Americans according to a May poll from Pew. Yet here’s the crucial part: Aren’t they, too, Walz’s—and our—neighbors? Then what would a neighborly approach require? Again, an earnest attempt to at the very least recognize their concerns. It might recognize, as the author Luke Burgis has suggested, advocating for better science to limit the number of embryos discarded in the practice. It would eschew simply dismissing these concerns as “weird.”

Despite Walz’s short-sighted references to imagined “shared commitments” and half-hearted, selective neighborliness, conservatives who value pluralism should acknowledge that he is at least paying lip service to unity. The right in the Trump era, meanwhile, has consistently painted the country in Manichean, apocalyptic terms, in which a woke left out to remake or even destroy America justifies seeing fellow citizens as enemy combatants.

That Republicans from Donald Trump to J.D. Vance have been far more divisive does not mean Democrats like Walz have been exemplars at building bridges. For those conservatives who find themselves on the wrong side of certain issues—especially social issues—neighborliness is seldom extended.

Nevertheless, Walz is right in this respect: Americans are starving for unity. As much as our politics is often driven by the loudest and most extreme voices, by some measures most Americans are part of an exhausted majority who reject “the sky is falling” view of the world. But a more confident pluralism will not require merely talking about unity; it’ll depend on actually recognizing the concerns of our political opponents, even amid deep-seated, often irreconcilable differences.

That’s a tall order, but it’s a necessary one for a more united democracy—and for a few less tense Thanksgivings.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.