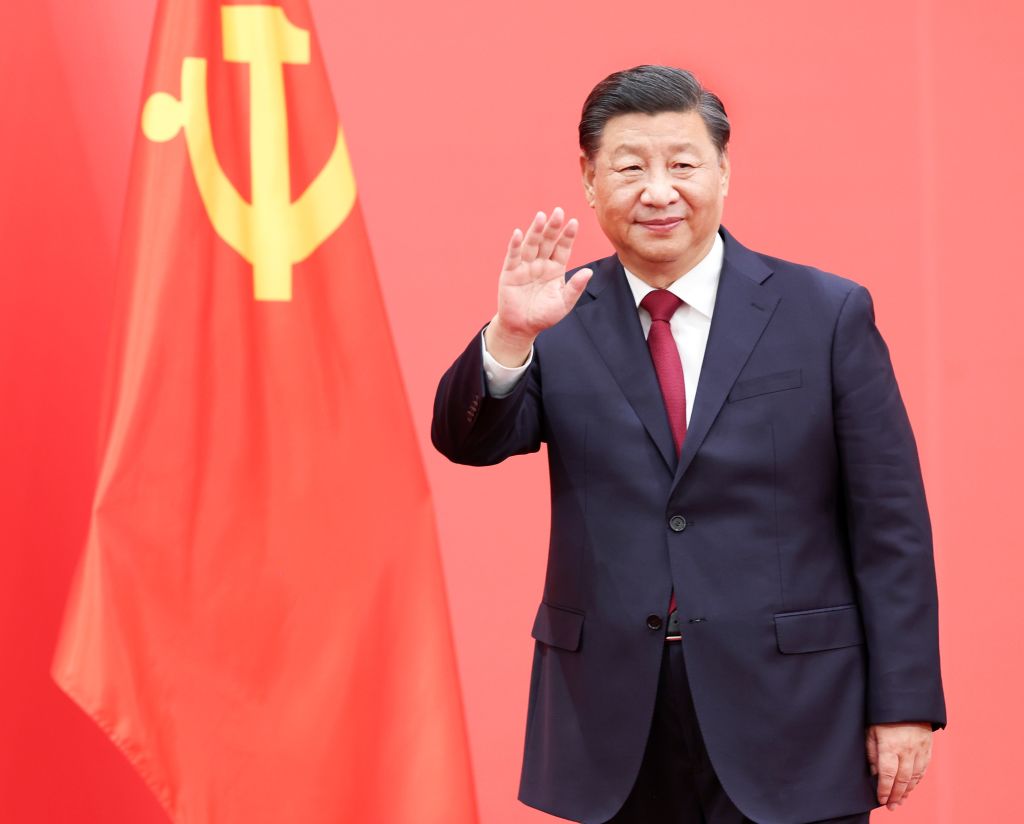

The Chinese Communist Party’s hardening repression at home and expanding influence abroad have brought the Washington-Beijing relationship to a modern nadir—increasing the risk of dangerous and destructive conflict. Current Chinese President Xi Jinping is the central driver of eroding relations, yet some of China’s problematic behavior precedes his rise a decade ago, as evidenced in the new book Hand-Off: The Foreign Policy George W. Bush Passed to Barack Obama.

Edited by former National Security Adviser Stephen J. Hadley, the volume compiles once-classified transition memoranda prepared by the outgoing Bush administration in 2008. Despite being prepared by outgoing administration officials 15 years ago, the documents shed a light on the concerning trajectory an emergent China has now taken.

Hadley expanded on the theme in an interview, edited for length and clarity.

The transition documents note concerns that China might overtake the U.S. as the world’s largest economy. Given China’s recently slowing economic growth, should this still be an immediate concern?

China is already now the world’s number two economy, but as you point out, its growth has slowed. The reason in some sense is because of strategic decisions that Xi Jinping and his regime have made. They have gone after the private sector and starved it for capital; declared war on some of their big internet companies because of their great economic and related political power; and inserted the party into the business sector—on the boards of directors of companies and the like.

Xi has, in some sense, killed the goose that laid the golden egg. I think China’s economy will still be robust, but as to when and if it will surpass the United States as the world’s largest, we’re probably some years away, maybe a decade away. But China’s economy is big enough to be a real challenge to the United States.

How would Chinese economic hegemony threaten American values and interests?

It has replaced the United States as the number one trading partner for most of the countries in Africa, Southeast Asia, and for many countries in Latin America. Chinese officials use their economic leverage to coerce countries to fall in line with their policies. The close economic ties between China and Africa explain why so many African countries were reluctant to join in condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, for example.

One of the reports in the book you edited states that “any optimistic policy outlook is predicated on a stable China.” How has the CCP’s domestic policy affected our relations with Beijing over the last 20 years?

During the Bush administration, China wanted a benign international environment so that it could focus on its internal development. It wanted to be a part of the international system rather than undermine it. It wanted a constructive relationship with the United States. It was also emphasizing reform and opening up its economy, moving toward more market-based approaches to its economy and even some political loosening up. That has really largely been rolled back.

Xi Jinping has asserted the party into every aspect of Chinese life and accompanied it with a real crackdown on any internal dissent. Party officials used COVID as an excuse to allow them to monitor behavior, monitor the movements of their population. It gave China the instruments of a totalitarian state that Joseph Stalin would’ve been delighted to have in his era. So what you’ve seen is a narrowing of any political space domestically. Limited though it was even in the time of the Bush administration, it is limited even more now. Dissent is almost non-existent.

At the same time Xi Jinping has grown China’s military to project power abroad. How is that different now compared to 20 years ago?

China has historically been a land power. What you’ve seen the last 20 years is China developing the capacity to project power with its air, missile, and naval forces out to what they call the first island chain—to Japan and beyond—and potentially out to the second island chain, which would reach all the way to Guam. China has made clear that they want to frustrate the United States’ ability to operate its air and naval forces within that area, and that makes it difficult for us to be credible in fulfilling our treaty commitments to countries like South Korea, the Philippines, Japan, and Australia. This is obviously troubling.

What about its activities in the South China Sea?

They have built these manufactured islands in the South China Sea, which they have militarized and are trying to treat as China’s lake by controlling international traffic there. A significant percentage of global trade goes through the South China Sea, so maintaining it as an international waterway with open access to all countries is terribly important. They are trying to threaten a declaration that the South China Sea is sovereign Chinese waters in the same way that the Chinese declared the Taiwan Strait not to be international waters. That is a potential flashpoint for a real confrontation between China and the United States and its friends and allies.

One of the Bush-era transition documents noted the common ground China and the U.S. found in recognizing the threat posed by global terrorism. Could any common issues or common adversaries lead to such cooperation today?

A lot of global issues today really won’t be solved if China and the United States can’t cooperate—pandemics, climate change, stability of the global financial system—so there are a lot of reasons why China and the United States should cooperate. But it’s very difficult for the two countries to do so. There are so many areas now where we are at odds—such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—and areas where we are competing with one another, such as high-tech industries and international infrastructure. So the problem is that the areas of competition between China and the United States have so grown that there’s the risk that that competition drives us to confrontation or even conflict. The Chinese, in some sense, have been holding cooperation on global issues like pandemics and climate change hostage to get better U.S. behavior and less competitive pressure in other areas. This is a far cry from the Bush years, when we had a very different China that wanted cooperation and wanted to be part of the international system.

Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, after the Bush administration. Is he the main factor of the current stress in the Sino-U.S. relationship?

Many people say the seeds of what Xi Jinping is doing were sown all the way back to Jiang Zemin, who was the leader from 1993 to 2003. And that may be true. But under the Bush administration we dealt with Jiang and Hu Jintao, and they were different kinds of leaders who seemed to want a more cooperative relationship.

Xi Jinping had a different agenda and became convinced of three things. One, that the West was in decline and the United States was in terminal decline. Two, this was a moment for China to try to take a central position on the international stage. Three, that the United States was in some sense the enemy, that the United States did not accept the legitimacy of Communist Party rule in China and was trying to undermine that rule through its support for freedom, democracy, human rights, and rule of law. So we have China today, which is much more aggressive in its diplomacy, ramping up its military power, and reaching outside its border to try to squelch any criticism of China’s policy. It’s encouraging division and discontent within the United States and within other countries around the world. So this is a very different China today, and I think it really proves the adage that who is leading a country really matters.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.