HBO is about to launch a miniseries on The Plumbers—Richard Nixon’s dirty tricks squad caught in the midst of the Watergate burglary. Judging from the commercials and comments from cast members such as Woody Harrelson, it looks like the series will be played for laughs. White House Plumbers is timed for the 50th anniversary of when the American people learned about the existence of The Plumbers and their nickname, from a court memo in one of the Watergate burglary trials that emerged in April 1973.

Nicknames have a long and amusing history in politics, dating back at least as far as the Roman Empire. But nicknames took off in American presidential politics before Donald Trump came on the scene and started giving out demeaning handles to his political opponents. (And even before George W. Bush, who was famous for doling out more affectionate monikers.)

The Plumbers owed their nickname to the fact that they were first employed to plug leaks. Nixon was obsessed with stopping leaks and catching leakers, especially after the disclosure of what became known as the “Pentagon Papers.” Nixon instructed his team to make sure that there would be no leaks and ordered wiretapping operations, and, oddly, a firebombing and break-in to the headquarters of the Brookings Institution as part of these efforts. The Brookings break-in never happened, but obviously the Watergate one did.

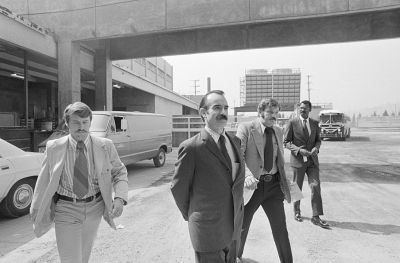

The members of The Plumbers were former law enforcement types and “spooks” (former spies). It’s not clear that these bumblers were ready for prime time, although a prime-time comedy series seems fitting. One of them, Tony Ulasewicz, had to go to the library to look up what the Brookings Institution even was before planning out the Nixon-ordered assault that never came.

Watergate was such a sprawling and bizarre scandal that it spurred many other nicknames beyond just “The Plumbers.” The most famous of them all may have been Deep Throat, the name the Washington Post editorial team assigned to the secret source who was feeding information to journalists Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein about the inner workings of the Nixon administration. Collectively, the two reporters had their own nickname: “Woodstein.”

The concept of Deep Throat did not become public until Woodward and Bernstein’s All The President's Men came out in 1976, but Nixon suspected that the Post had a source in the FBI long before he ever knew the name Deep Throat. In fact, Nixon even suspected that FBI Deputy Director Mark Felt was the leaker, decades before we learned that Felt was in fact Deep Throat.

Felt himself had a nickname within the FBI, “the white rat”—because of his white hair and his “tendency to squeal.” Felt was not above ginning out nicknames, calling his boss FBI Director Pat Gray, “Three-Day Gray,” for his frequent absences from FBI headquarters. Felt's resentment at having been passed over for the top job by the often-missing Gray led to his leaking against the Nixon administration in the first place.

Within the White House, the propensity for giving out nicknames started at the top. National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger had a host of nicknames for his boss, including “that madman,” “our drunken friend,” and “the meatball mind.” Nixon’s own chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, would refer to his boss as the “Old Man,” “Rufus,” and “P,” for “president.”

Nixon had nicknames outside the White House as well. Watergate prosecutor Richard Ben-Veniste, reflecting his team’s desire to show that Nixon was at the heart of the scandal, referred to their target as “Le Grand Fromage”—French for “the Big Cheese”—which he would shorten to “GF.”

Haldeman and Kissinger were both of German descent, as was domestic policy adviser John Ehrlichman. For this reason, they were known collectively as “the German Shepherds,” “the Berlin Wall,” “the Fourth Reich” and “the King’s Krauts.”

Other top White House players who scored nicknames were the White House’s legal counsel on Watergate matters J. Fred Buzhardt, and hard-working Ehrlichman aide Egil Krogh. Buzhardt was, unsurprisingly, known as “Buzzard,” but fellow aides apparently put more thought into names for Krogh. His sobriquets included “Evil Krogh,” “the White House Mr. Clean,” and “my Bob Cratchit.” Like his boss Ehrlichman, Krogh would go to jail as a result of the scandal.

Some of these nicknames, specifically Deep Throat and, as the new HBO show demonstrates, The Plumbers have lived on in the American consciousness. Most of them are more obscure, and many readers may be learning of them for the first time here. But the proliferation of this many nicknames over this short of a period point to the intensity of the White House scandal within Washington, when pressure, high stakes, and scandal led a lot of Type-A personalities to direct their brainpower to cutting the non-stop tension with memorable and humorous nicknames. Now, half a century later, we can appreciate their creativity, even as we breathe a sigh of relief over the fact that our system held together through a challenging crisis.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.