Peter Navarro, one of President Trump’s top trade advisers, wrote a memo in late January 2020 warning of potentially dire consequences for American citizens and the U.S. economy if the federal government didn’t swiftly implement active “containment” measures, including a ban on travel from China, to stem the growth of the COVID-19 virus. When Axios revealed the memo earlier this week, the news rocked Washington: Think of the immeasurable pain and uncertainty that might have been avoided if Trump and his other advisers had just heeded Navarro’s warning. The only problem was, nobody did.

In isolation, the White House’s inaction appears to be a major policy blunder, possibly responsible for needless human and economic casualties. In context, however, much of the blame shifts to Navarro himself, and to his fellow economic nationalists in the White House. Their constant reliance on “national security” and “national emergency” hysterics caused others in the Trump administration (and the country more broadly) to tune them out. As one White House adviser put it, “The January travel memo struck me as an alarmist attempt to bring attention to Peter’s anti-China agenda while presenting an artificially limited range of policy options.” In short, when the real China emergency arrived, nobody paid attention to the guy who spent the last three years running around the West Wing yelling that everything China touched was an emergency. In so doing, America lost valuable time and, of course, much more.

It’s a sad episode—and one that reveals a fundamental flaw in the nationalist mantra that “economic security is national security”: it turns out that, when everything’s a national security threat, sooner or later nothing is—not even the real one.

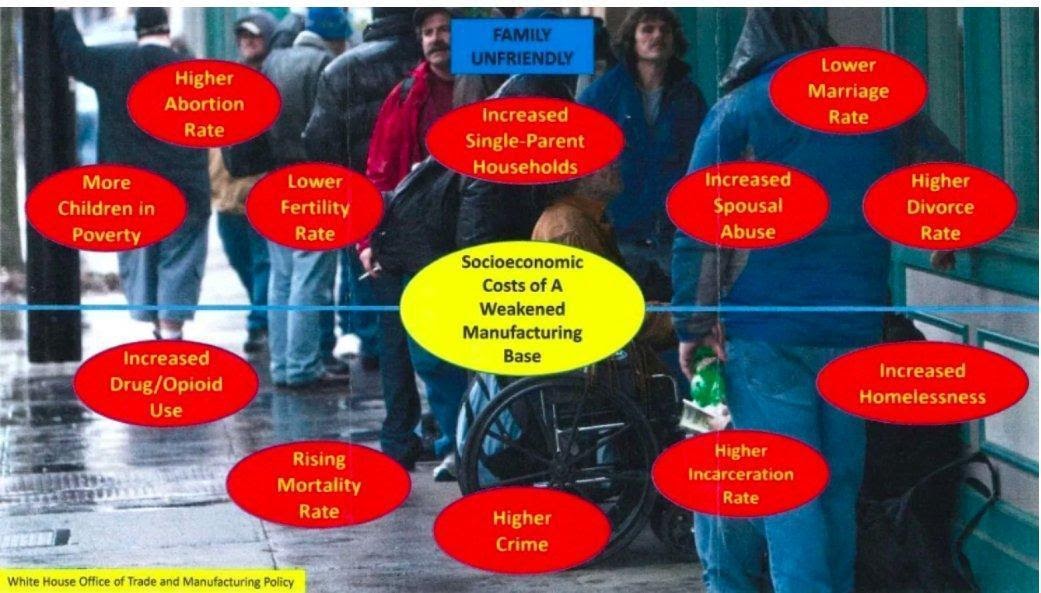

That mantra is actually the title of a 2018 op-ed by Navarro, the White House’s most famous China hawk and the author of such subtle pre-White House works as Death by China, Seeds of Destruction, and The Coming China Wars. Navarro’s talent for finding trade-related crises also is not limited to China. Among the other “national security” threats he’s identified in recent years are: 1) overall and bilateral trade deficits; 2) foreign direct investment into the United States; 3) agricultural imports; and 4) “outsourcing.” While in the White House, Navarro was also the author of an infamous Cabinet-level presentation tying—without any empirical support—U.S. trade agreements like NAFTA to not only economic calamities like lost jobs and closed factories, but also social ones like abortion, low fertility, spousal abuse, divorce, crime, drug abuse, and even death.

And these are just the dire Navarro warnings we know about. Is it any wonder, then, that when Navarro circulated his somewhat-prescient (although dubiously reasoned) coronavirus memos, nobody in the White House listened to him? Are those advisers really to blame? Or was it simply impossible for any right-thinking person to distinguish between the real warning and the numerous “NAFTA causes abortion” warnings that preceded it?

It’s a wonky update to The Boy Who Cried Wolf, and were this problem isolated to Navarro, the parable could end here. Yet Navarro’s views on the many alleged security threats posed by America’s international economic engagement are not the insular ramblings of a single White House character but instead permeate Trump administration trade and immigration policy.

Over the last three years, in fact, the White House has repeatedly used liberal interpretations of U.S. law to find “national security threats” and “national emergencies” where no previous administration dared to look. In early 2018, the administration deemed steel and aluminum imports into the United States to threaten national security and justify protectionist tariffs and quotas under the rarely used Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. This “threat” included metals from not just China or other notorious trade scofflaws, but also close allies like Canada, Mexico, the EU, and Japan. Further, the tariffs were not applied just to the specialized metals we might need for tanks, satellites and planes, but boring commodities like steel slab and rebar (yes, rebar). Indeed, before Trump imposed these tariffs, the Department of Defense itself explained that global import restrictions were unnecessary because DoD needed at most 3 percent of current U.S. production of those metals and because the vast majority of imports came from reliable sources like the aforementioned allies—the same reason the George W. Bush administration came to the exact opposite conclusion regarding steel and national security in a 2001 Section 232 investigation requested by two members of Congress (the last one until Trump arrived).

In 2019, the administration again found a national security threat under Section 232, but this time it was global automotive imports, not metals, that threatened us. If you’re wondering how a Ford from Mexico or Mercedes from Germany imperils the nation, I unfortunately can’t tell you because the official report making those findings remains secret—despite new congressional legislation, passed and signed by the president, directing its release. Nevertheless, what we do know is bad enough: According to the presidential proclamation announcing the automotive “threat,” the administration’s theory of the case was that imports and foreign investment in U.S. factories was somehow a “national security threat” because “[t]he United States defense industrial base depends on the American-owned automotive sector for the development of technologies that are essential to maintaining our military superiority.” Thus, the millions of Americans who make and sell “foreign” cars in the United States presented a “serious risk” to “American innovation capacity.”

I kid you not.

Then there’s China—which Secretary of State Mike Pompeo recently called the “Central Threat of Our Times.” You’ll find near-universal agreement—even among free traders—that China and certain Chinese trade and investment practices have the potential to raise legitimate security concerns. However, the administration’s shotgun-and-sledgehammer approach—notably, broad-based tariffs on practically everything, regardless of any security nexus, an opaque tariff “exclusion” process that reeks of political favoritism, and an investment screening net so wide that it caught the gay dating app Grindr—raises serious questions about the policy’s efficacy and objectives. For example, if the proudly protectionist Trump administration was truly worried about China’s high-tech or essential medicine supply chain superiority (instead of just wanting more protectionism), then why were they tariffing low-tech things like furniture, toys, and shoes?

It’s not just trade, either. The president raised eyebrows in 2019 when he declared a “national emergency” under the National Emergencies Act—and vetoed a joint congressional resolution opposing the declaration—so that he could divert billions of dollars in DoD appropriations from military construction to his border wall. According to the official proclamation, “[t]he current situation at the southern border presents a border security and humanitarian crisis that threatens core national security interests and constitutes a national emergency.” Left unanswered, of course, was why the White House waited to address this 'security crisis' until after the GOP lost its majority in the House of Representatives.*

Trump threatened another emergency declaration, as well as tariffs on all Mexican imports under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA), due to Mexico’s unwillingness or inability to slow “caravans” of Central American refugees heading for the United States. IEEPA grants the president vast powers to regulate “transactions in foreign exchange,” but only where he finds that there is “an unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States, to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States” and “declares a national emergency with respect to such threat.” It also has never been used to impose tariffs on imports from a close ally (instead being reserved for specific transactions or bad actors). As such, the legal and security grounds for using IEEPA to tariff everything from Mexico due to a surge in refugees is unconvincing (at best).

And this brings us back to the current moment. Navarro, Trump and their allies in the administration in Congress today insist that decades of unfettered globalization have left America, particularly its pharmaceutical and industrial supply chains, unprepared for COVID-19 and in desperate need of “repatriation” through a radical mix of protectionism and industrial policy. They have further announced that they intend to use the current crisis as a springboard for implementing their long-held economic nationalist wish list in order to solve this clear national security threat. Maybe, with respect to certain specific sources or items, they have a point. Maybe they don’t.

But after years of declaring everything from Chinese toasters to Canadian aluminum to Guatemalan children a national security crisis, why on earth should we believe them now?

Scott Lincicome is an international trade attorney, adjunct at the Cato Institute and visiting lecturer at Duke University. The views expressed are his own.

Correction, April 10: The piece originally said that the GOP lost its majority in both chambers of Congress in the midterm elections. The GOP actually lost the House but gained seats in the Senate.

Photograph of Peter Navarro by Drew Angerer/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.