As a question of law and public policy, I’m an old-fashioned let-your-freak-flag-fly libertarian, “consenting adults in the privacy of their own home” and all that stuff, and, in that respect, I do not very much care whether Mark Robinson—the modern GOP’s “third-most popular black Nazi”—consumes great quantities of pornography or what kind of pornography he consumes. I do not even care very much about his fantasy acting-out on the message boards of a pornographic website. Eros, too, is a jealous god, and, at times, an unusually savage one.

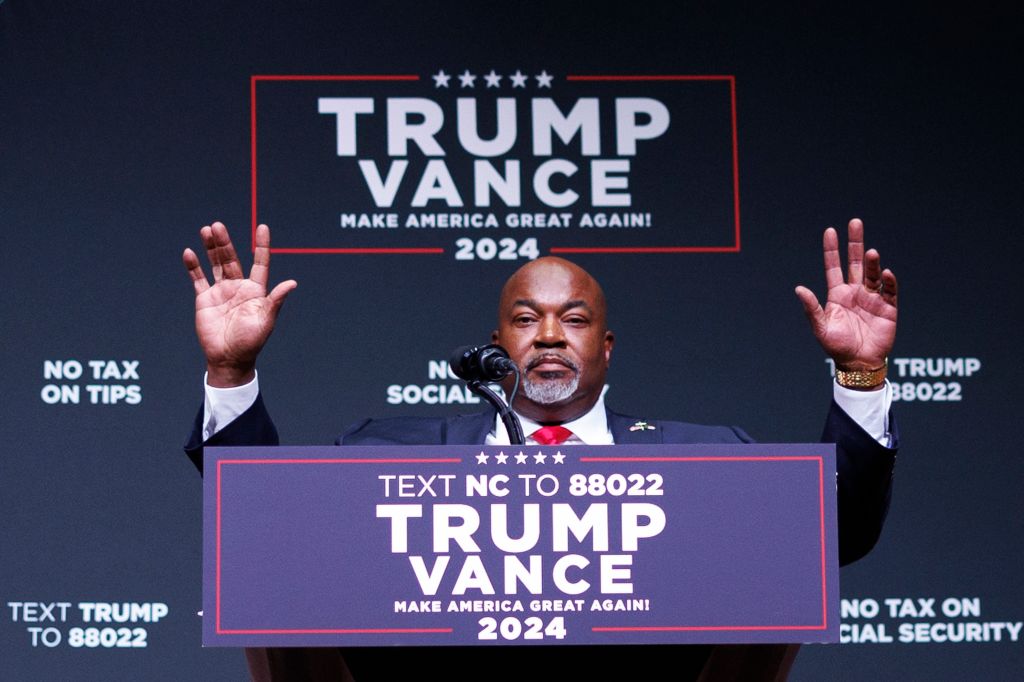

I’ll even nod solemnly and try very hard not to roll my eyes as I note that Robinson—the Republican candidate for governor of North Carolina and the state’s current lieutenant governor—says this is all made up, a hit job concocted by ... somebody. I’ll stipulate and concede and tolerate a great deal.

Just don’t ask me to pretend that I’m surprised.

It is worth reiterating that the Trump movement is led by Donald Trump, who is himself an occasional performer in pornographic films, a former buddy of Jeffrey Epstein who described him as a “terrific guy” with a manful appetite for women “on the younger side,” whose businesses have in many cases been scams (Trump “University”) or exercises in utter incompetence (his ownership of the Plaza, the casinos again, Truth Social, six bankruptcies in 18 years, etc.), who has sustained his fortune not with savvy real-estate investments but by working as an advertising mascot for Mammon and as a game-show host. He is very weird about women (Trump’s current wife is a former employee of the modeling agency he set up to secure proximity to such women) and he named his youngest son after the imaginary friend he invented to lie to the New York Post about his sex life. Trump has never, to my knowledge, called himself a Nazi, and I do not believe Ivana Trump’s claim that he regularly read a book of Adolf Hitler’s speeches. A book of Hitler speeches is still a book, after all, and I am not engaging in hyperbole when I write that I very much doubt he has ever read a book all the way through.

It is not really true that opposites attract. Ivy Leaguers tend to be friends with and marry other Ivy Leaguers, and evangelicals tend to spend a lot more time with other evangelicals than with militant atheists. Vegans socialize sadly with other vegans. Most of us end up in churches, clubs, schools, neighborhoods, marriages, friendships, and careers where we are surrounded by people who are a lot like us. It is not the opposite that attracts but the adjacent. Trumpworld is a satellite of Pornworld.

Donald Trump plays a special role in the Republican Party and on the modern right, but the movement he personifies did not begin with him. Populism has always been thick with crackpots (Ross Perot), grifters (Steve Bannon), and degenerates (Matt Schlapp), and, in more than a few cases, people who ticked more than one of those boxes, such as Sen. Strom Thurmond.

Thurmond is an interesting example: He is today and forever rightfully associated with the cause of racial segregation, but, before his 1948 “Dixiecrat” presidential campaign, Sen. Thurmond had been seen as something of a moderate on race. Not an integrationist, mind you—this was a South Carolina Democrat in 1948—but someone who publicly abjured extremist rhetoric and abusive language, and who was notably praised by the NAACP after working to see to it that a group of white men who carried out an infamous lynching were arrested and tried for their crime. (They were acquitted.) Thurmond seems to have latched onto the issue of segregation not out of any particular passion for racial politics but because he thought it was a good issue to ride to national prominence. And it worked: He became a gargoyle, and gargoyles are prominent.

Thurmond was a canny politician, and he saw a brighter future for himself in the Republican Party than with the Democrats. Ensorcelled by the prospect of poaching a Democratic senator and gaining a foothold in the kind of politics Thurmond represented, the Republican Party was far too eager to welcome a defector they should have rejected, with William F. Buckley Jr. writing in his syndicated column that Republicans “will do well to be generous” with Thurmond on matters such as seniority, in the hopes of inspiring others to follow. Which others? Buckley names segregationists such as James Eastland, Herman Talmadge, Sam Ervin, and a bunch of other people the GOP would have been better off without. Imagine an alternative history in which Republicans said, “Thanks, but no thanks” to Sen. Thurmond et al. It is a happier timeline than our own.

In the end, Thurmond was practically alone among major Democratic segregationists to actually switch parties—an early example of conservatives being too willing to sell their souls at an embarrassingly low price. Buckley would, to his credit, come to regret his earlier obdurate line on civil rights, but the right’s temptation to accommodate the immoral and the disreputable in exchange for the merest whiff of political advantage is a mistake that Republicans have repeated over the decades.

Sen. Barry Goldwater had an excellent record on civil rights and opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 on defensible constitutional grounds—which, to put it generously, wasn’t universally the case among his fellow opponents. Goldwater knew that he was making common cause with a raft of bigots and crackpots, and, rather than drawing the necessary lines and making the necessary distinctions—and paying the necessary political price for doing so—he was determined to “hunt where the ducks are,” as he put it. There wasn’t anything inherently wrong with Republicans’ effort to appeal to voters who were thrilled with the racial rhetoric of Thurmond or George Wallace by presenting to them good policies that appealed to the better part of their political characters—that is a lot of what the much-misunderstood “Southern Strategy” was about—but doing so brought with it the temptation to accommodate that which should not be accommodated and to gloss over the indefensible.

The stakes aren’t always as high as they were in the post-war years. But Republicans knew that figures such as Christine O’Donnell (the “I am not a witch” lady from Delaware) were grifters and crackpots and that the Tea Party movement was attracting more than its share of these. It was also clear to anybody who was paying attention that that the Tea Party movement was not conservative and that it was intellectually incoherent, but Republicans wanted to get into the protest game and leapt headlong—again—into a populist morass from which they have never quite emerged. The Tea Party movement was the soil in which the belladonna of Trumpism was planted and took root. The theater of populism, like all theater, has its roots in ritual, and its real meaning is its meaning as ritual, as performance: Pay attention to us! This is the story we are telling about ourselves and our world! It doesn’t matter if it is true, but it isn’t really about facts or history—it is about the pursuit of status, about aspiration.

In that regard, the kind of pornography that Robinson was commenting about is less interesting than the fact that he felt compelled to make public comments about his taste in pornography, albeit from behind the protective veil of anonymity. Some individuals—and some communities—have a powerful need to be seen, to be observed, as though they are only able to experience their lives in a secondhand way, through the observation and reactions of others. These are the people who seem to think that they cease to exist when they are not being looked at—or, in the case of Donald Trump, when they are not being talked about. Trump’s weird obsession with audience sizes, ratings, rally attendance, etc., is well-known, and he seems to believe that he is—or he aspires to be—the most talked-about person in human history. (Sorry, Jesus!) It’s like a radical version of the observer effect: The observer brings the phenomenon into existence ex nihilo. (And think about that void!) Trump’s political career hasn’t been hindered by his social-media addiction—his political career serves his social-media addiction, and that is its only real purpose beyond keeping him out of jail.

Experiencing life’s most intimate moments secondhand through the mediation of pornography is a natural complement to that mentality. The reason people have absurd and self-dramatizing social-media lives is the same reason people make sex tapes or watch others’ sex tapes. Marshall McLuhan had it less right than did Jean Baudrillard: It isn’t that the medium is the message, it is that the signifier has entirely supplanted the thing signified, swallowing it whole like an ortolan. Life is not for living—it is only a necessary input for the creation of content.

Melania Trump, the third lady, has been busy defending her lesbian-porn-ish nude-modeling work from ... nobody, as far as I can tell. The subject had not been raised in some years, but the need to be talked about—to be seen—does not just go away when your public profile begins to fade, as Mrs. Trump’s has. Of course, there are financial considerations—she has a memoir to peddle—but it isn’t just that. It is never just that. Mrs. Trump desires to be something grander than ... whatever it is she is calling herself these days. That dream of reinvention also is part of the populist spirit.

Donald Trump at one point tried very hard to start a rumor that he was romantically involved with Carla Bruni, the French singer and wife of former French President Nicolas Sarközy. Mrs. Sarközy was sufficiently embarrassed and inconvenienced that she complained publicly about the lie. She is an extraordinarily beautiful woman, and one could easily understand why a man would wish to be connected with her; but Donald Trump did not wish to actually be connected with her, only for people to believe—to say—that he had been connected with her. To understand the difference between the former desire and the latter is to understand Trump in full—and about 80 percent of Trumpism, too.

One imagines (one does not enjoy imagining) Mark Robinson, self-described “black Nazi” and pornography enthusiast, sitting at his computer, typing obscene comments awkwardly with one hand, when an idea enters his head: political office, the public life perfecting the pubic life, the lonely voyeur hitching a ride on American Greatness and being carried to previously unimagined heights of ecstasy, an orgy of being seen and of approval. If you want to call him a pervert, think first of his political ambitions, obscene beyond the merely pornographic imagination.

The libertarian in me does not much care what he does in the privacy of his own home.

The libertarian in me also very much wishes he would have kept it there.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.