A blood-red sky in Manhattan. Killer heatwaves in the Southwest. Floods besieging Vermont. Welcome to Revelations 2023.

Is this the end of the world? Not likely. But there’s real cause for concern and a pressing need for an honest debate about tradeoffs and solutions for climate policy.

Whenever extreme weather is in the news, the debate tends to be dominated by the Climate Alarmists and Climate Atheists, pseudo-religious camps that view their calling as either exaggerating or diminishing risk. The goal of these camps isn’t an honest pursuit of truth or a measured consideration of evidence but pandering to constituencies who expect their biases to be confirmed.

Case in point: The Wall Street Journal recently published an op-ed in which the author refuted the claim that the Earth just had its hottest day in 125,000 years. I’m all for questioning “the science,” yet this debate misses the point. Just as one hot day or month doesn’t prove the earth is facing an imminent ecological collapse, no single exaggerated claim invalidates the argument that unusually hot days will become more frequent when the earth is warming.

Making sense of the moment requires clear thinking and a revival of the journalistic ethic that says getting the right facts is as important as getting the facts right.

Two right facts stand out in the climate debate.

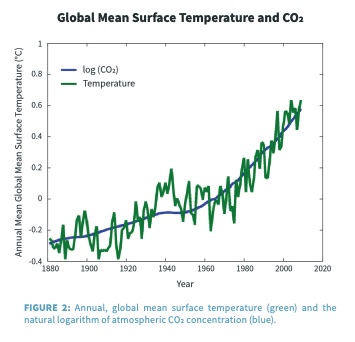

First, the evidence since the Industrial Revolution points to a strong correlation between increases in greenhouse gases like CO2 and higher global temperatures. The increases aren’t consistent, but there is a clear upward trend line (see below). There are good reasons to look at what happened 125,000 or 1 million or 100 million years ago (the last time current CO2 was this high was 3 million years ago when sea levels were 80 feet higher), but the best first step for anyone curious is to look at the recent past. The past 150-year trend line is consequential and tough to untether.

Kerry Emanuel at MIT, who is no alarmist, concisely unpacks this correlation in a thoughtful primer. Emanuel also offers good counsel on how to think about science:

Scientists rarely refer to “facts” or speak about anything being settled. We are by our very nature skeptical … In climate science, the word skeptic was hijacked some time ago by the media and certain political groups to denote someone who, far from being skeptical, is quite sure that we face no substantial risks from climate change. The vast majority of climate scientists, as well as all scientists, are truly skeptical. Science is a deeply conservative enterprise: we hold high bars for reproducibility of observations and experiments, and for detecting signals against a noisy background.

I’ve pressed Emanuel to be specific about his level of concern and, like a good scientist, he won’t go there. Instead, he refers to the concept of “tail risk,” which is how the insurance industry thinks about risk. Tail risk is at the right of a probability table and depicts a low probability but highly adverse outcome like having a house fire this year (1-in -3,000 chance). In the climate debate, the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates there’s a 90 percent chance global temperatures will rise between 1.8 and 4.6 degrees Celsius (about 3 to 8 degrees Fahrenheit) over the century. There’s a 5 percent chance temperatures will be lower and 5 percent chance they’ll be higher. Climate Alarmists depict the 5 percent scenario as a 100 percent certainty, but because the risk is greater than zero it’s smart to think about fire insurance.

Acknowledging this correlation shouldn’t trigger an ontological shock for conservatives when the debate about solutions overwhelmingly favors a center-right response.

Enter the second the right fact: Economic cooling won’t stop global warming.

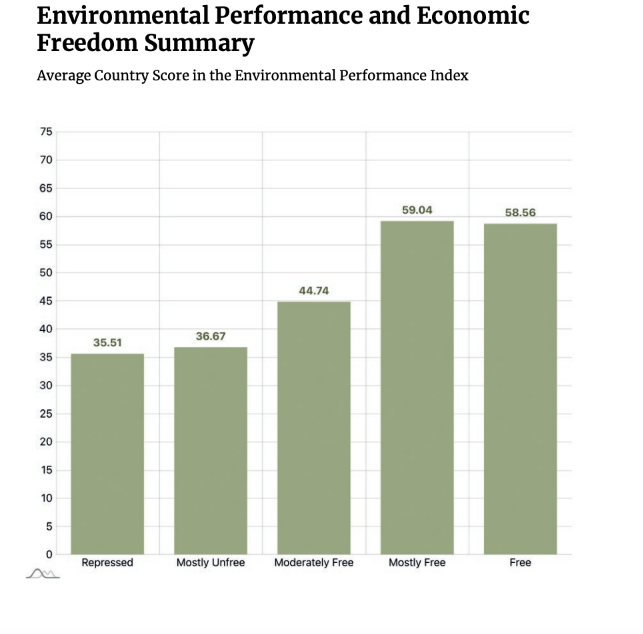

The economics of the climate debate are more settled than “the science.” When Nick Loris, vice president of public policy at C3 Solutions, overlaid (below) the Yale Environmental Performance Index on top of the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, he found that free economies around the world (i.e. those with streamlined regulations, low spending, low taxes, private property rights, etc.) are almost twice as clean as less free economies. In the foreword to the paper, Ed Feulner, the former president of the Heritage Foundation, channeled Milton Friedman by saying, “Economic freedom encourages people to ‘own’ their environment, and they do a better job of taking care of it.”

History demonstrates that economic growth and innovation lead to better environmental outcomes. For thousands of years burning trees fueled the growth of civilization. Cities that want to ban charcoal grills forget that our distant ancestors became human when we learned to cook food with fire, which redirected metabolic energy from digestion to brain growth.

As we unwittingly flirted with an environmental catastrophe through felling oxygen-producing trees in the 18th century, the economic growth from tree burning helped us discover coal and fossil fuels. As cities like London struggled with a growing problem of horse manure on crowded streets near the end of the 19th century, the answer didn’t come from central planners, but an innovator named Henry Ford. In the 20th century, after fossil fuels saved the planet and lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty through advances in agriculture, sanitation, transportation, and medicine, we discovered that carbon emissions from fossil fuels cause global warming.

If we allow innovation to work, including economic activity powered by fossil fuels, the problem of global warming will be solved by better technologies.

The public intuitively understands that this is how the world works. Polling consistently shows that Republicans, not just Democrats, overwhelmingly believe humans are contributing to climate change and feel the warm blanket of rising temperatures in their daily lives. When our organization asked Republicans if they believed in climate change, only 14 percent said it isn’t happening. And 70 percent of Republicans said human activity is a primary or contributing factor.

We also found that the public overwhelmingly favors (by a 2-to-1 margin) a conservative approach to climate solutions that emphasizes smart regulatory reform over lavish borrowing as well as an “all of the above” energy strategy over the dogmatic “everything but fossil fuels and nuclear” strategy embraced by some on the left. House Republicans wisely used these principles as their framework for H.R. 1—the Lower Energy Prices Act. Many Republicans bragged that the bill would also lower emissions.

In a heat wave, this raises a question: Why make a weak argument—diminishing climate risk during record high temperatures—when you could be making a strong argument by explaining why economic freedom is the answer?

In the coming years, winsome persuasion may be crucial. If unlikely weather events become more common, the public may have a “break the glass” moment that empowers a future leader to declare a “climate emergency” and impose a top-down, command-and-control economic cooling policy. One can argue that has already happened in Europe, where bad energy policy, such as Germany’s decision to wind down its nuclear plants while outsourcing carbon emissions to Russia, helped encourage Vladimir Putin to invade Ukraine. And, in the U.S., the Biden energy policy is de-growth lite. Biden has erected new barriers to American oil producers while asking dictators to produce more. Never mind the fact that dictatorships create more CO2 than American producers, and those molecules don’t need a visa to cross our borders.

When conservatives fail to think critically or scientifically about climate, the problem is not that they fail to see the flaws in the other side’s argument but that they fail to see the strength of their own argument. Acknowledging that the world is getting hotter gives us the opportunity to make the case for economic freedom.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.