Last week, the House of Representatives passed a bill that would prevent “potentially hundreds of thousands” of noncitizens from voting in U.S. elections, according to House Speaker Mike Johnson. Five Democrats joined Republicans in approving the legislation despite no evidence of widespread noncitizen voting in any state and prohibitions already in place against it.

“We all know, intuitively, that a lot of illegals are voting in federal elections. But it’s not been something that is easily provable,” Johnson said last month. In fact, non-U.S. citizens have been barred from voting in federal elections since 1996. But for some on the right, conspiracy theories about election security that surfaced following the 2020 election not only persist but are spurring renewed scrutiny of voting practices, particularly in states likely to be battlegrounds in November.

In actuality, states already have effective measures in place to prevent election fraud. Here’s a look at voter registration rules and identification requirements at each step of the voting process in selected states, including Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, and Pennsylvania, considered among the key swing states in November.

Checks When Voters Register

Efforts to ensure election security begin with registration. States such as Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Nevada have automatic registration through their motor vehicle departments. “Most Georgia voters register or update their registration when they get or renew their Georgia driver’s license,” Mike Hassinger, a spokesman for the Georgia Secretary of State’s office, told The Dispatch. In 2021, Georgia overhauled its election laws, ushering in provisions for cleaning its voter registration lists and tightening absentee voting ID requirements, among other changes.

“The start of election security and integrity is the registration process, where we check for U.S. citizenship before a person can be registered to vote,” Hassinger said. “Because the Georgia Department of Driver Services is Real ID Compliant, the Department of Driver Services database is used to verify the citizenship of most applicants.”

In Georgia, some people applying to register to vote are verified through the Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlements (SAVE) database, which checks a person’s citizenship status, giving registration lists an extra layer of protection from non-citizens making it onto voting rolls. States such as Arizona and Colorado also use the system. In every state, however, voters are required to affirm, under penalty of perjury, that they are a U.S. citizen at the time of registration. This serves as a backstop against fraud, especially for states that do not conduct more comprehensive citizenship checks.

Arizona requires voters to provide proof of citizenship during registration. The state requests one of several documents such as a driver’s license, state ID, or passport as verification. If citizenship cannot be verified, then the person is registered as a “federal-only” voter, allowing them to vote in federal elections but not state and local elections. According to the New York Times, Arizona has close to 20,000 of these federal-only voters, who are still required to attest they are U.S. citizens under penalty of perjury.

Some states’ registration requirements are less stringent. For example, Nevada does not use SAVE, but to register online, by mail, or in person, voters still must provide either a Nevada ID or a Social Security number. If they do not have either of these, the voter will be contacted by the county election department and would be required to go to the county clerk or registrar’s office to show an alternate ID and proof of residency in order to register, according to Cecilia Heston, the public information officer for the Nevada Secretary of State’s office.

According to that office’s website, registration information is “sent to the Secretary of State’s office during the nightly upload process where it is verified against the Nevada Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV), the Social Security Administration (SSA), the Office of Vital Statistics, and existing records within the Statewide Voter Registration List.” Georgia, Pennsylvania, Arizona, Colorado, and other states verify voter rolls using equivalent databases.

Nevada also compares voter data with other states using the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC). To prevent election fraud, ERIC compares voter records among 24 member states and Washington, D.C. ERIC is a nonprofit organization founded by chief election officials from seven different states, and it is controlled by a representative from each member state. States pay a one-time membership fee of $25,000 and annual dues that depend on the state’s population.

Despite these safeguards, a potential loophole exists that could allow non-citizens to vote in Nevada. When counties verify IDs, the DMV confirms only whether a driver’s license or ID is valid; it does not return any information about citizenship. Because legal U.S. residents who have not obtained citizenship can get a Nevada driver’s license, a non-citizen with such a license could register to vote if they lied about their citizenship status on the registration application. However, Heston explains that more than 99 percent of Nevada voters have a Nevada voter ID or driver’s license along with their Social Security number attached to their voter registration information, indicating they are citizens.

Because of its looser voter ID and mail-in ballot laws, the Heritage Foundation’s election scorecard ranks Nevada 50th in the country for “election integrity.”

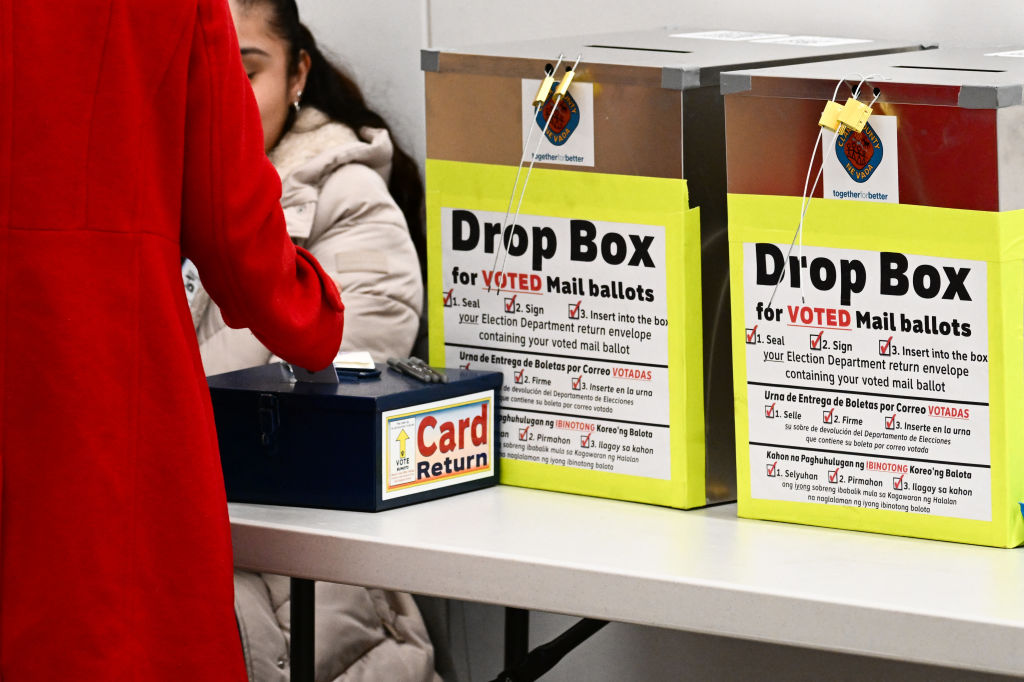

Rules About Absentee Voting

Absentee voting and mail-in voting sparked a firestorm of conspiracy theories after the 2020 election, but states have processes in place—some of which existed before the 2020 election—to keep ballots secure.

Registered voters in Georgia and other states can request an absentee ballot without an excuse, but a signature is still required, along with a valid ID number or a copy of a document that shows the voter’s name and address. In Texas, voting absentee is more difficult: A voter must meet one of five criteria to receive an absentee ballot. The voter is also required to provide an acceptable Texas ID number or their Social Security number to verify their identity.

Eight states, including Colorado and Nevada, send mail-in ballots to every registered voter. According to the Survey of the Performance of American Elections, more than 85 percent of Colorado voters did not vote in person in 2022, but the state has multiple defenses against fraud. It uses signature verification to confirm voters’ identities, and first-time mail-in voters must provide a photocopy of one of several acceptable IDs. Nevada uses signature verification, as well, and it requires first-time voters who do not appear in the DMV or Social Security Administration databases to submit both an ID and proof of residency when voting mail-in.

ID Requirements at the Polling Place

When it comes to election security at the polls, there are three categories of states: those that require a photo ID to vote, those that require a non-photo ID to vote, and those that don’t require an ID to vote.

Georgia requires voters to show a photo ID. If a voter forgets their ID, election workers can provide them with a provisional ballot.

“They have three days after Election Day to come back and what we call ‘cure’ [the provisional ballot]. For example, they would go back to their house, get their driver’s license or some form of government-issued photo ID, and show it to the election worker,” Hassinger said. “And [the election worker] would move that provisional ballot out of provisional status and into eligible status.”

In Arizona, voters must present either one photo ID or two non-photo IDs like a utility bill or bank statement. If the voter does not have sufficient identification, they can then also submit a conditional provisional ballot and provide an ID within five days.

States that have less-strict ID laws use other rules aimed at maintaining election integrity. Pennsylvania, for example, does not require people who have voted previously in the state to present an ID, but all first-time voters are required to bring a photo ID or a non-photo ID that contains their address. If these voters cannot provide an ID, they can submit a provisional ballot. The county board of elections would then decide within seven days whether the ballot would be counted.

Nevada does not require ID to cast a ballot in person. However, each voter’s signature is compared to the signature on their registration application. If a voter is not registered on Election Day, they can still register at the polling place just before voting. Voters who use same-day registration are required to have a Nevada ID or driver’s license.

“What happens is that they would register to vote at the polling place with same-day voter registration, and then they cast a provisional ballot, so the county verifies that voter’s registration before counting the ballot,” said Heston of the Nevada Secretary of State’s office.

After the election, Nevada—like 47 other states—conducts a post-election audit to verify the results of the election. In its statewide audit of the 2016 election, Nevada found only three non-citizen voters.

In fact, non-citizens voting in federal elections is a rarity. Ohio found 137 non-citizens who were registered to vote—a tiny fraction of Ohio’s nearly 8 million registered voters—and the state is now expanding its verification measures. In 2016, North Carolina found 41 non-citizens who cast votes. That was out of nearly 5 million votes cast. In a citizenship review of Georgia voting records conducted in 2022, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger’s office found that 1,634 non-citizens attempted to register to vote from 1997 to 2022, but none were successful.

In Arizona, where concerns about non-citizens voting prompted legislative changes by the state’s GOP-controlled legislature, a federal judge who struck down parts of two 2022 laws found that it was “quite rare” for a non-citizen to cast a vote.

With the security measures that are in place in each of these states, there is a vanishingly small chance of fraud significantly swaying the results of November’s election.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.