Three years ago, Florida and Texas passed laws prohibiting Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube from engaging in viewpoint discrimination—forbidding them from “censoring” content or “deplatforming” users. NetChoice, a trade association of e-commerce businesses, sued both states to challenge their authority to impose these restrictions. The laws are enjoined for now, after the 11th and 5th Circuit Courts of Appeals issued conflicting decisions. Today, the Supreme Court will hear arguments in both cases.

The states will argue, among other rationales, that they have authority to enforce these laws because the social media platforms are “common carriers.” The problem? No one seems to know what a common carrier is.

The term first applied to businesses that transported goods, but over the years courts have imposed “common carrier regulations” on everything from utilities companies to grain elevators. At the same time, they’ve expressed uncertainty about whether internet service providers or cable operators count. Justice Clarence Thomas inspired further debate (and perhaps even the Florida and Texas laws) when he suggested in a 2021 concurrence that some digital platforms “resemble traditional common carriers.” But he struggled—like everyone else—to define exactly what a common carrier is.

However we choose to define “common carrier,” the stakes are high. Common carriers lose some of the legal privileges of private companies and become subject to stricter regulation. For instance, if a common carrier denies someone equal service, that person can sue for damages. That’s a common law rule—no legislation required. (In fact, if the Supreme Court decides social media platforms are common carriers, the Texas and Florida anti-discrimination laws won’t matter. The platforms would be subject to common law tort claims by anyone across the nation who was denied equal service.)

Despite the many failed attempts at a definition, history points us to a straightforward answer: Social media platforms are not common carriers.

Texas’ definition is at once overinclusive and underinclusive.

In NetChoice v. Paxton, Texas argues that “the centuries-old calling card of a common carrier is that it does not ‘make individual decisions, in particular cases, whether and on what terms to deal.’” This is often referred to as the “holding out” test. A common carrier “holds out” to serve the public without individualized bargaining.

Imagine if this were the true definition of a common carrier. It would presumably include every local doughnut shop (or barber or grocery store or auto mechanic). Have you ever walked into one of those that made an “individual decision” about whether to serve you or on what terms? Me neither. So either a doughnut shop is a common carrier, or this can't be the whole definition. It’s overinclusive.

The definition is underinclusive, too. Under Texas’ definition, companies could evade common carrier regulation merely by stating they make individual decisions on what terms to deal. Consider water and electric utilities—companies that have historically been subject to common carrier regulation. Once they’ve established their networks in an area, they don’t pick and choose which people they’ll serve. Now imagine a water company announcing that it will do business only via individual bargaining. It stops “holding out” to serve the public. Does Texas’ definition mean that the water company wouldn’t be a common carrier and courts couldn’t require it to serve citizens indiscriminately? (I’m not sure I buy this argument. But several scholars raise it as a problem with the “holding out” standard.)

Texas does hedge its bets by noting that “courts sometimes consider other factors.” The state says you might be a common carrier if you:

- operate in the “communications” industry,

- possess “market power,”

- benefit from “government support,” or

- are “affected with a public interest”

Aside from the first of those factors, the other three share something important in common—no one could possibly know what they include and what they exclude. These definitions are the dream of any judge who wants to impose whatever standard he or she chooses. They’re the nightmare of any judge who wants to simply “call balls and strikes.” Is the common law definition of common carriers really this indeterminate?

What About Florida?

Florida claims the common carrier doctrine “has long extended to those who ‘disseminate’ or facilitate the speech of others.” The state points to historical regulation of telegraph and telephone companies for support. But does this now mean that every bookstore or record store is a common carrier? Each “disseminates ... the speech of others.”

These examples aren’t what common law courts had in mind when they assumed extra regulatory power over ferries, innkeepers, and public utilities.

So what should the Supreme Court do? Is every definition too narrow, broad, or nebulous to adequately capture the historical meaning of “common carrier”?

Yes, every definition fails. What the court should do instead is to provide exactly two clear definitions.

Why we need two definitions.

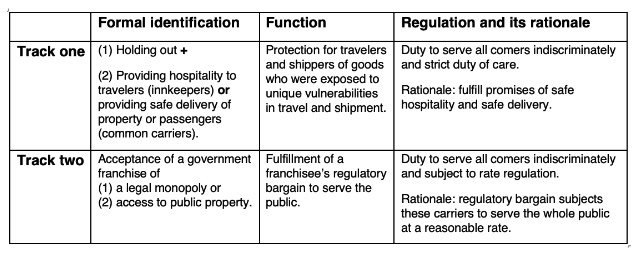

The long history of common carrier doctrine shows that it developed along two separate tracks. Each track has a different formal test, a slightly different regulatory regime, and a different functional rationale for the regulation. The reason modern courts and scholars seem to miss that point is that businesses on both tracks were often referred to simply as “common carriers,” even though they were classified that way based on different characteristics and for different purposes.

Whenever we attempt to merge the tracks, we develop an unsatisfactory rule or a dubious balancing test. Keep the tracks separate, though, and each rule comes into focus. As I’ve detailed at length, we can simply describe the two types of common carriers as “track one” and “track two” carriers.

Track one carriers are identified by two elements: 1) they “hold out” to serve the public without individualized bargaining, and 2) they either carry goods as bailees or they host traveling strangers. Think of ferries, innkeepers, and FedEx. Common law courts required anyone in this group to serve all comers equally. The courts also held them strictly liable for the goods they carried.

Courts justified imposing higher standards on this group because travelers and people who shipped goods were uniquely vulnerable. Common carriers and innkeepers, meanwhile, were uniquely positioned to exploit those vulnerabilities. Without legal protection, a traveler who relied on an innkeeper’s services risked being stranded, and someone shipping goods risked embezzlement. Imagine, for example, you ship a money order via a common carrier and the carrier says he was robbed along the way. Who should bear responsibility? Common carrier doctrine says the carrier does. That way he can’t fake the robbery and steal the money.

The history explains why several courts—including, finally, the Supreme Court in Primrose v. Western Union Telegraph Company—decided that telegraph companies don’t belong to this first group of common carriers. They “are not common carriers” because they “are not bailees, in any sense.” Telegraph messages “cannot be the subject of embezzlement,” so the rationale for subjecting telegraph companies to strict liability for their transmissions didn’t fit like it did for companies that offered delivery of physical goods.

You might be surprised by that. Telegraphs are common carriers, no? They are—but of a different kind. They’re track two carriers.

A track two carrier is identified by a single element: its acceptance of a franchise of government power. When a company accepts access to a power or privilege typically reserved to the government, it becomes “invested with a public interest.” Specifically, if a company receives access to public property or the right to exercise a legal monopoly, it’s a track two carrier.

When telegraph companies used eminent domain or public rights-of-way to string their lines, they engaged in a “regulatory bargain” with an implied agreement to serve the public. If they’d used eminent domain power without the implied bargain to serve the public, it would have violated the Takings Clause (and before the 14th Amendment, similar clauses in state constitutions).

The logic of track two carrier regulation is straightforward: If the government gives public property or power to a private business, that business must use what it has received to serve the public indiscriminately. Otherwise, it would constitute a public taking for private use.

Now we see why most public utilities have been subject to common carrier regulation. They required access to public property—and sometimes a legal monopoly—to develop their extensive infrastructure networks. In exchange, they agreed to serve everyone in the area equally.

Table 1: Form, function, and regulation of track one and track two carriers

The two-track theory resolves each of the problems above.

Recall my earlier examples: doughnut shops, a water company that stops “holding out” to serve the public, and book and record stores. The track one and track two definitions resolve questions about each.

My local doughnut shop isn’t a common carrier, even though it doesn’t “make individual decisions about whether to serve or on what terms.” That’s because it doesn’t carry goods for its customers. It can’t embezzle my property because it never takes custody of it. Yes, the doughnut shop holds itself out to serve the public indiscriminately, and that can make it a public accommodation. But that doesn’t make it a common carrier.

What about a water company that announces it will only do business via individual bargaining—it says it doesn’t “hold out” to serve the public? These definitions don’t let it off the hook. If the track one definition were the only definition of common carriers, the water company might evade its public duty. But under track two, if the company accepted special access to public property when it ran its pipes, it implicitly agreed to serve the public. Businesses that accept access to public property can’t dodge their public duty by not “holding out.”

And what about bookstores and record stores? Even though they “disseminate the speech of others,” they look more like a doughnut shop and less like a telegraph company under this analysis. They don’t carry anything for their customers, and they haven’t accepted a public franchise. Once again, they might be public accommodations, but they wouldn’t qualify as either type of common carrier.

The two-track theory also explains why many of Texas’ other cobbled-together factors are often present in common carriers but don’t determine whether a company is a common carrier.

Texas’ claim that participation in the communications industry can make someone a common carrier confuses correlation for causation. Most communications providers—phone companies, cable TV, and internet providers—need access to public property to develop their networks. That makes them track two carriers, because of their use of public property, not because of their general affiliation with the communications industry.

Same for the “market power” factor Texas uses. Companies that develop large infrastructure networks will often have outsized “market power.” But the “market power” is a result of the networks they built using government franchises. A company’s market power doesn’t, on its own, make it a common carrier.

Finally, Texas’ other proposed standards—government support and public interest—do fit the historical definitions of track two carriers, but only if we make them more specific. A common carrier does “enjoy government support,” but so does every business that receives a tax incentive. The rule has to be narrower to match its historical form and purpose. We need to ask whether a business has received government support in the form of a legal monopoly or access to public property, not just whether it has received any government support. Same with Texas’ fourth factor: “affected with a public interest.” The phrase had a fixed meaning in its original context. Businesses that enjoy the kind of government support I’ve just referenced are invested with a “public interest.” The rest are not.

Now apply this to social media platforms.

Track one: Social media platforms obviously don’t fit the track one carrier standard. They serve the public without individual bargaining, so they can be regulated as public accommodations. But just as telegraph companies aren’t track one carriers because they aren’t bailees, neither are social media platforms.

In his 5th Circuit NetChoice opinion, Judge Andrew Oldham called the physical carriage requirement a “wooden metaphysical literalism.” That’s because he misunderstood that literal carriage is a key element if this part of the doctrine is supposed to protect against embezzlement. Oldham also complained that telegraphs can’t be common carriers if physical carriage is required. He nearly got that right. They’re not this kind of common carrier. He just missed that a second kind exists.

Track two: The historical track two standard doesn’t fit the platforms, either. They haven’t received eminent domain authority or public rights-of-way from the government. And the government never granted them legal monopolies so they could develop without competition.

Instead, the track two argument relies on other ways the government has supported the companies—most notably via Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. Section 230 immunizes the platforms from lawsuits that treat them as speakers when others use their platforms to speak. That means Facebook can’t be sued for someone’s libelous posts or comments. Texas and Florida say that kind of government support converts a company to common carrier status. History doesn’t support that argument, nor does constitutional reasoning.

True, many common carriers have received special immunities from the government. But governments have historically granted those immunities because a business was regulated as a common carrier. They didn’t use the immunities to convert a business into a common carrier.

Constitutional reasoning doesn't support the Section 230 argument.

Consider what happens if states can impose common carrier obligations on any company by giving it some kind of immunity. To take an example of states trying to regulate businesses on other grounds, Colorado could grant all bakeries and web designers some benign immunity, then declare they’re common carriers that can be regulated differently than other companies. The state would argue that Masterpiece Cakeshop and 303 Creative no longer apply because bakers and web designers no longer enjoy the same constitutional protections as other private companies. Whether that would be a winning argument is uncertain. But it’s the argument Texas and Florida are making.

The Supreme Court could resolve the NetChoice cases on other grounds, but I hope the court doesn't miss this opportunity to resolve the common carrier question. Otherwise, the problem will continue to bedevil courts. A two-track definition would get us out of the strained definitions and indeterminate balancing tests that run throughout today’s doctrinal mess.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.