Ask someone about the best decade for music and chances are they’ll look back at their adolescence. Baby boomers believe the greatest music hits were created before 1970. Millennials hold up the 1990s as an exemplar. And for Generation Z, it’s after 2010.

But after conducting a new study on Gen Z’s formative experiences, I’m wondering whether their teenage years might be considerably different—and less positive—than those of previous generations, musical nostalgia notwithstanding.

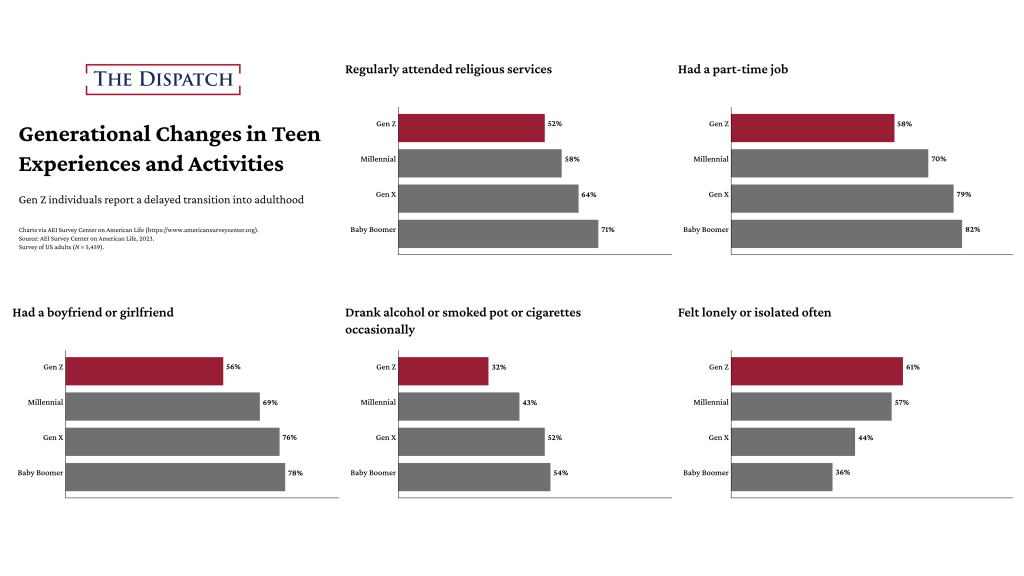

Gen Zers experience major life milestones much later in life. In previous generations, dating and relationships were quintessential parts of the teen experience. Less so for Gen Z. Fifty-six percent of Gen Z adults say they had a boyfriend or girlfriend as a teenager, compared to 76 percent of Generation X and 78 percent of baby boomers. Young adults today are also less likely to have worked as teens. Eighty-two percent of baby boomers report that they worked a part-time job during their teenage years, compared to only 58 percent of Gen Z.

Only 42 percent of Gen Z men say they participated in outdoor activities like hunting, scouting, and camping as teens—a remarkable 25-point gap between them and their baby boomer counterparts. Involvement in teen sports is also lower among Gen Z men, though Gen Z women report greater participation in youth athletics than women from previous generations.

And the list goes on. Religious participation is down, continuing a decadeslong decline. Drug and alcohol use are significantly lower as well. (While religious involvement is negatively related to drug and alcohol use for older generations, for Gen Z these two activities are not connected.) Most concerningly, loneliness and disconnection are more common features of teen life. Sixty-one percent of Gen Z adults say they felt lonely often during at least some part of their teen years, compared to only 36 percent of baby boomers. Teen therapy is up too.

There isn’t a single factor responsible for these changes in teenage experiences, but the role of technology undeniably looms large.

The rise of smartphone-enabled social media dramatically changed how young people communicate with each other, access information, and think about themselves and their peers. A growing body of research has found social media contributes to mental health problems, especially in teen girls. Social media also profoundly reduces incentives to spend time with people out in the world. It’s certainly no accident that Gen Z spent less in-person time with friends than any previous generation. The pandemic invariably played a part in all of this, but social media is exerting an even stronger and more sustained influence on teen socializing.

Parenting behavior has also significantly affected the teen experience. Americans are having smaller families and investing much more time and energy into their children than ever before. As I’ve written before, investing an inordinate amount of time and energy in this or that enrichment activity is probably not a good thing.

Not surprisingly, Gen Z adults, and especially Gen Z women, are more likely to have taken private art or music classes than previous generations. More than one-third of Gen Z women report having been enrolled in private art or music classes during their teen years. Private tutoring and intensive travel sports have become more common as well, especially among more affluent households.

Many parents have helped their kids develop college-bound CVs by emphasizing enrichment activities and curating unique experiences. But this comes at the expense of time spent hanging out, dating, and working—messy and sometimes difficult experiences that are nevertheless invaluable.

Partly as a result, friends play a less central role in the lives of today’s teens than they once did, especially for boys. In 1990, nearly half of young men said that the first person they would turn to when facing a personal problem would be a buddy. Half as many do so today. Young men now are more likely to turn to their parents than their friends.

The United States has a strong tradition of older people fretting about the moral standards, work ethic, and popular tastes of young people. It’s quite possible that as a Gen Xer, I am simply engaged in the time-honored pursuit of hand-wringing about the youth.

Still, it’s worth considering whether Gen Z is missing out on some pretty fundamental experiences. Typically, when I ask elder millennials and Gen Xers about this, they express relief that their youth was spent without smartphones recording every embarrassing or mundane moment. Gen X, who spent their entire adolescence free from social media, spent the most time hanging out with friends in person.

Members of Gen Z are hardly oblivious to the impact technology has had on their teen years. It may well be that 20 years from now Gen Z looks back appreciatively on the way technology and social media shaped their adolescent experiences. But given what we know about the impact of technology on teen loneliness, social disconnection, and anxiety, it’s quite possible that their feelings will be less rosy.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.