Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

I used to dislike dress codes, and, in some ways, I still do. But I have come around a little.

When I was in high school, we had a fairly restrictive dress code, with a particular emphasis on policing the length of shorts and skirts, which did not inconvenience me personally inasmuch as I was not much inclined to wear either but which did cause some discomfort for some of my more heat-sensitive peers. Our school was a brick building constructed in 1901 and had no air conditioning, which is a serious thing in Texas. It is serious enough that a Texas judge recently ruled that lack of air conditioning in Texas prisons amounted to unconstitutional cruelty. I will spare you my lecture about the similarities between public-school architecture and carceral architecture.

This being the late 1980s and early 1990s, there was also a good deal of Satanic panic in the air that influenced the dress code, and our local school superintendent caused a bit of a furor by circulating a list of “occult” symbols for teachers to be on the lookout for—one of which was the Star of David. That would have been bad enough for the ... I think three ... Jewish families with students in our school, but the cherry on top of the hot-buffoonery sundae was that the superintendent’s last name was “Moses,” which was a gift to the editorial cartoonist at my high school newspaper. The local superintendent went on to be the state education commissioner and the superintendent of schools in Dallas, enjoying an excellent reputation in both roles. Perhaps he grew on the job, like his namesake.

Public school students are (as the architecture suggests) a kind of captive population, which inclines me toward a more liberal approach to regulating their outfits, but I have come around on dress codes elsewhere. I lived in Las Vegas for a time, and I can tell you that you will not see Sean Connery in a dinner jacket at the baccarat table in any of the casinos there—you will see a lot of board shorts and flip-flops. Casino gambling is going to be gross one way or the other, but I’d still prefer if it were a black-tie affair. Similarly: I try to avoid fancy restaurants, but I recently met a friend for dinner at a nice place where the reservation confirmation came with a gentle reminder that the establishment maintains and enforces a dress code. Not much of one, to be sure, but a general prohibition on sweatpants and that sort of thing. I remember a heat wave in Philadelphia so intense that the Union League club briefly relaxed its requirement that men wear a tie to lunch, and I regretted that a little bit, even though I myself probably looked a little funny with my blue blazer and tie on my motorcycle. (The coat-check clerk never seemed to know what to do with my helmet.) The WASP-y septuagenarian gentleman who was my usual host at the Union League knew something about standards of dress: “It’s always a special occasion when I meet you for lunch,” he said. “I’m wearing my second-best toupée.” At that time, Philadelphia nightclubs advertising on the local rap stations made a point of emphasizing their dress codes: “No sneaks, no Tims,” one put it succinctly, “Tims” meaning Timberland boots. In the cartoon that goes with my pieces (the one where I look like the snooty butler in a 1980s comedy), I’m wearing a tuxedo for a wedding (not mine) at Lake Como, and it just wouldn’t have been the same if everybody had been dressed like we were tailgating before the Texas-OU game. On that score, I prefer how they tailgate at the Radnor Hunt, with women in fancy bonnets and many guests arriving by carriage—steeplechase isn’t peewee football.

What matters about a dress code is, at heart, what it is intended to do.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, who had a short and undistinguished if perfectly honorable low-level military career before he became an undistinguished if perfectly anodyne low-level talk-show host, recently hauled in almost every general and admiral in the U.S. military for a command performance during which he lectured them about, among other things, military dress and grooming standards. As one senior officer remarked after Hegseth’s dorky, strutting performance, it could have been an email.

Hegseth indulged his pogonophobia in particular:

No more beards, long hair, superficial individual expression. We’re going to cut our hair, shave our beards, and adhere to standards. If you want a beard, you can join Special Forces. If not, then shave. We don't have a military full of Nordic pagans.

Point of fact: We do have a few Nordic pagans in the military, a fact that has come up from time to time in a different area of presentational standards: tattoos. Religious tattoos are generally acceptable (with certain limits, mainly regarding size and placement) under military rules, but neo-Nazi, racist, and hate-group symbols are not. There’s some crossover between the benign (if excruciatingly silly) neo-pagan stuff and the white-power knucklehead stuff. Would-be soldiers can be rejected because of such tattoos, and soldiers in service can be discharged for regulation-violating ink. You would think that Hegseth would know this, inasmuch as a great deal of attention has been paid to his own tattoos—including a Jerusalem cross and the slogan “Deus vult,” both of which are associated (though not exclusively) with sundry far-right, racist, fascist, or neo-Nazi movements, as indeed are many other medieval Christian symbols. The reactionary nutjobs like to imagine themselves as Teutonic knights practicing what Hegseth calls the “warrior ethos.” They are, in the main, dorks.

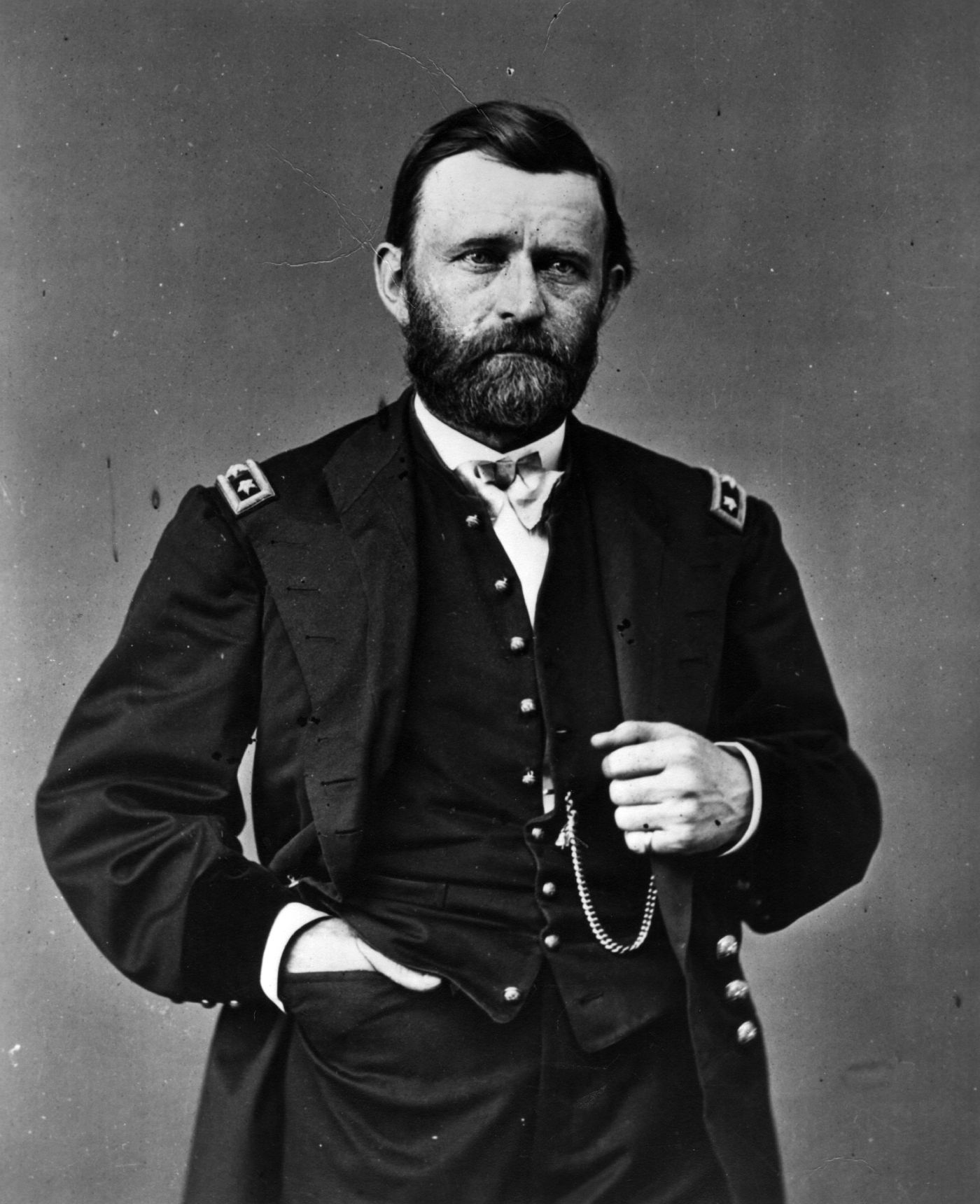

The United States has had bearded soldiers for a very long time, including some of our best: Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman leap to mind. In World War I, British national Bhagat Singh Thind, who was studying in the United States at the time, joined the U.S. military to go and fight the Germans, and did so wearing a beard and turban. He was, as you might have guessed from his name, a Sikh, and Sikhs have a long and proud military tradition: Japanese troops trying to invade India via Burma during World War II ran into a wall of beards and turbans, which were the last things many of them saw. Naik Nand Singh of the 11th Sikh Regiment, who never hosted a Fox News program, was a genuine badass who captured a series of German positions, some of them single-handedly, after being shot in the leg and the face, and he was awarded the Victoria Cross for his bravery. He was killed by short-range machine-gun fire in the Indo-Pakistan War, and the Pakistanis, after parading his corpse through a nearby city—he was a very famous soldier by that point—disposed of his body in a garbage dump, from which it was never recovered. Beard or no beard, he would be too good to serve under such a figure as Pete Hegseth.

I will believe that Hegseth is serious about this stuff when Hegseth starts acting like he is serious about it. As a few observers have pointed out, Hegseth’s Beverly Hills, 90210-style sideburns often extend to a length that would be prohibited under military grooming standards. But there is another area of dress convention that Hegseth violates in practically every public appearance, one that is in fact relevant to his current position: the Flag Code.

The Flag Code is written into federal law, though there is no penalty for violating it. It forbids wearing the flag as an article of clothing, a rule Hegseth routinely flouts with his dopey flag-lined suits. It specifically forbids using the flag as a handkerchief, which Hegseth does habitually, tucking it into his chest pocket as a decorative pocket square—and surely, surely not because doing so makes it look like he is wearing some kind of military decoration. Hegseth, Donald Trump, and the members of the movement they represent are habitual violators of the Flag Code, which is not merely an aesthetic concern.

Part of the point of the Flag Code is the notion that the flag is not to be treated as though it were merely an item of personal property. It is not to be used for tawdry, tacky, or self-interested purposes such as advertising. Hegseth has obvious contempt for rules of this kind, and Trump has equally obvious contempt for any kind of rule that would put any kind of limitation on his self-aggrandizement and vanity. You can be sure that if Hegseth or Trump preferred to wear a beard, then beards would be mandatory in the military, possibly even for women.

What should be understood is that Hegseth is not a patriot, and his flag abuse is not a sign of patriotism in any meaningful sense of the word. What Hegseth has done—and what Trump and his cult have done much more significantly—is to transmogrify patriotism into a category of identity politics, just as they have done to Christianity. Patriotism is not a self-transcending duty to country–it is a self-aggrandizing tribal marker, like Hegseth’s tattoos. Donald Trump has never had a sincerely Christian impulse in all his nearly 80 years walking this Earth. As he made clear during his plainly heretical performance at Charlie Kirk’s memorial service, his religious sensibility, to the extent that he has one, is pagan, oriented toward glory, reputation, and earthly things. But he treats Christianity as a kind of badge, brandishing a Bible from time to time. (He ought to try reading one.) Trump, of course, has only the pagan vices, and not the pagan virtues: He loves the idea of manliness and martial heroism, but when his country came calling to ask him to fight, he showed himself to be a plain sniveling coward, reportedly paying a doctor to invent a medical condition that kept him from being drafted—a condition that magically went away, with no treatment, as soon as the threat of glory had passed.

His tattoos aside, Hegseth has nothing in common with the crusaders who gave up a great deal—from physical comfort to, in many cases, their lives—in the service of what they believed to be a Christian mandate. Hegseth is more of a camp-follower, part of one of those trains of merchants and prostitutes that long followed armies into battle for self-interested commercial reasons. His flag displays are a matter of—to borrow Hegseth’s own words—“superficial individual expression.”

I know something about that.

The allure of delusional self-adoration can be powerful. When a junior high vice principal made me cut my hair (picture your obedient correspondent at 15 with a blond Robert Smith-circa-Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me rats’ nest), I was much offended. I believed, in the sincerest possible way, that I was a unique, very special, possibly heroic 15-year-old, one destined for great things, and, above all, one whose autonomy and personal sense of self had to be respected at all times, damn the rules. It all seemed incontrovertible at the time. But I am not in junior high school anymore. Pete Hegseth somehow is. Princeton owes him a refund.

And his tailor owes him an apology.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.