One of the main strategies—arguably the main strategy—taken by Senate Democrats during the Senate confirmation hearings for Amy Coney Barrett has been to portray her as an existential threat to the Affordable Care Act. The attack hinges on Texas v. California, a lawsuit filed by 18 Republican state attorneys general that seeks to overturn the ACA. Oral arguments are scheduled for November 10.

The suit is widely considered to be a dead end, but Democrats’ political instincts to focus on a threat to Obamacare are correct. For example, the legislation’s provision forbidding insurance companies to deny coverage to people with pre-existing conditions is immensely popular: 72 percent of the public believes keeping the provision is “very important,” including 62 percent of Republicans.

President Donald Trump has consistently said that those with pre-existing conditions would be covered in any plan that replaces Obamacare, even signing a (largely toothless) executive order declaring that those with pre-existing conditions would retain coverage in the event of an ACA repeal. He tweeted in June that he would “ALWAYS PROTECT PEOPLE WITH PRE-EXISTING CONDITIONS, ALWAYS, ALWAYS,ALWAYS”—typical of his public rhetoric on the matter.

Yet while a majority of Republicans think that Trump would do a better job than Democrats on protecting those with pre-existing conditions, only 38 percent of the broader public agree with that claim. That dynamic was a crucial factor in Democrats’ widespread success in the 2018 midterm elections, where the story of their victory was less about much-hyped progressive insurgents and more a tale of moderates who consistently warned voters that Trump and the GOP were planning to take away their health care.

There’s a reason for the disparity. President Trump’s administration has pursued policies at odds with his professed interest in protecting coverage for those with pre-existing conditions. He came into the White House in 2017 with “repeal and replace” of the ACA as a clear priority. But after multiple proposals in the House, then Senate, the final, exhausted attempt at a “skinny repeal” was voted down, with Sen. John McCain a dramatic last-minute vote against. While some protections for patients with pre-existing conditions were proposed in the 2017 negotiations, some versions of the repeal bill, especially the House’s, would have weakened them.

Subsequent challenges to Obamacare have come in the form of enforcement and regulatory changes enacted by the executive branch, as well as the court challenge mentioned above. While rules on pre-existing conditions have not been changed, changes in rules governing “short term plans” have had an indirect effect on patients with pre-existing conditions.

Short-term plans are free from the requirements that mandate insurers must cover pre-existing conditions and those who have them, and they were intended to serve as three-month stopgaps by the Obama administration. The Trump administration extended the time limit to 364 days, with the possibility of insurer-granted extensions extending it to three years. In effect, these cheaper, less regulated plans created a second market for insurance, which many Democrats warned at the time would draw customers away from the broader insurance market, and subsequently drive up premiums for those with pre-existing conditions.

But President Trump and other Republicans have insisted that the fundamental protections for those pre-existing conditions would remain untouched. Tom Miller, a health care analyst at the American Enterprise Institute, says, “If you wanted to, in a perverse way, give Trump credit, you could say that the totality of his actions have actually reinforced and extended support for the protection of the restrictions on pre-existing conditions across the board.” The administration’s effective abolition of the individual mandate in 2017 “basically took away the main source of opposition to the Affordable Care Act,” says Miller. In the 2018 elections, when Republicans were asked why they opposed the ACA, “they had a little more trouble coming up with an answer and they had to immediately say, ‘but I don’t want to get rid of [rules protecting people with] pre-existing conditions,’” Miller noted.

Of course, failed attempts at “repeal and replace” and some regulatory tinkering, along with a public commitment to protecting those with pre-existing conditions, do not make President Trump seem like a committed opponent of Obama-era protections. But his administration is nevertheless actively working to end coverage for just these people. Trump’s Justice Department has joined the 18 states opposing the ACA in California v. Texas, filing a brief that argues that the Supreme Court should strike down the entire law along with the individual mandate, including the section referred to as “guaranteed issue” which mandates coverage for people with pre-existing conditions.

The president, then, has taken entirely contradictory positions on a major issue, as he has so many other times in his tenure. He loudly and insistently proclaims his allegiance to protections for those with pre-existing conditions while Justice Department lawyers argue for overturning those very protections. And as on many other issues, those positions are held together by the promise to use his dealmaking skills to craft an even better replacement, with details to be filled in later. But in the unlikely event of the ACA’s nullification or repeal, Miller noted, Congress would most likely “grimace and they would end up passing if not exactly the same thing, something similar to it, because they lack the imagination to do something more creative.”

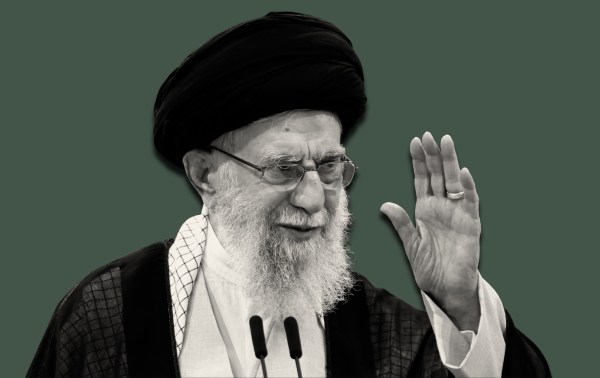

Photograph by Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.