In the early 1980s, I was the minority staff director on the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, serving under Democratic New York Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, vice chairman of the committee. It was an especially interesting time to be working on the staff, as questions about verifying arms control agreements, covert action programs, espionage cases, and insurgencies and counterinsurgencies in Central America and Afghanistan kept everyone busy.

At the time, the committee’s membership included some of the Senate’s biggest heavyweights— Chairman Barry Goldwater, Sens. Daniel Inouye, Richard Lugar, and Henry “Scoop” Jackson—but it was designed to be more bipartisan than others. Unlike most committees, the ranking minority member was the vice chair and, hence, the acting chairman when the chairman was not present and the two parties’ staff directors shared information. In a traditional committee structure, the next senior member in the majority presides when the chairman is not available. This design, along with the ideological diversity within parties that still existed in that era—with hawkish Democrats, more liberal Republicans, conservative Republicans, and more liberal Democrats—made it possible to work across the aisle. Nevertheless, given the contentiousness of the committee’s topics, it was a never-ending dance to construct a working majority on any given issue.

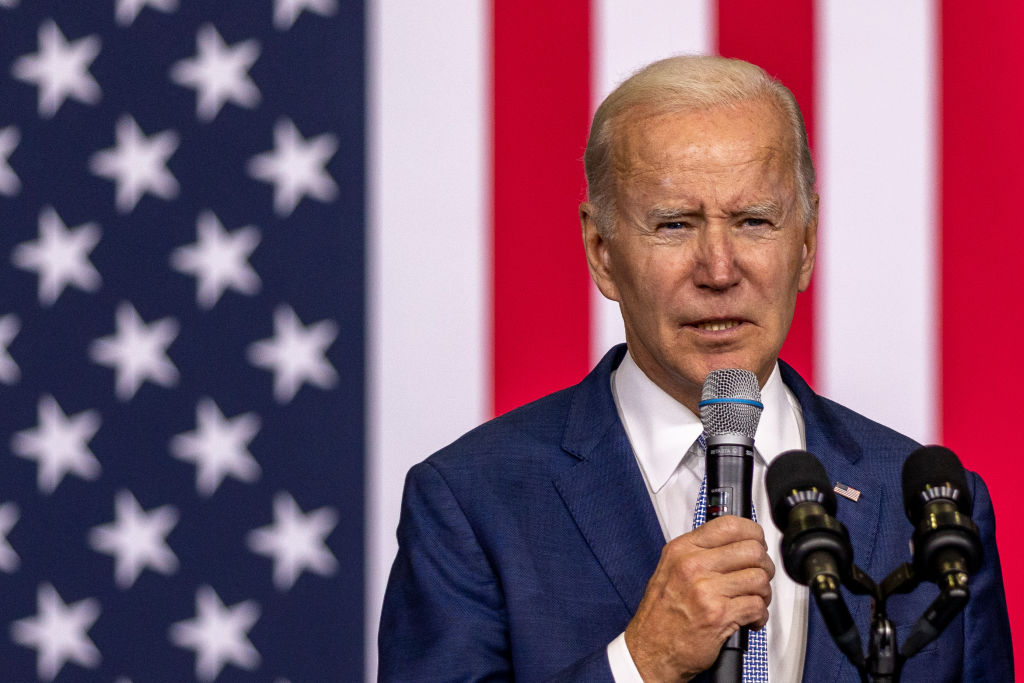

You could learn much about the ways of the Senate and Washington if you paid attention. And one senator whom you couldn’t help but pay attention to was the Democrat from Delaware, Joe Biden. Though only in his early 40s, he was already in his second six-year term, and like a few other youngish senators at the time, he believed he was the next John F. Kennedy.

Among the reasons you couldn’t ignore Biden was his habit of going off script. There were a number of times that he would begin to make a statement or just ask a question and more than a few minutes later you’d begin to wonder how he had gotten from point A to point B, with even more uncertainty as to when, if ever, he would get to point C, a conclusion. Indeed, with the overwhelming number of committee hearings behind closed doors, on several occasions other senators signaled their impatience to me as Biden rambled on with a witness. His staff had almost certainly prepared questions and background material far more focused than what he was actually saying.

As senators were wont to do back then, they never publicly vocalized their displeasure with the bloviating, but they undoubtedly wondered, as senior staff did, what was behind the undisciplined way of speaking. Did he want to show somehow that he was the smartest guy in the room—that he knew better than staff or the other senators? Was it a compensation mechanism for his stutter—once going, he just didn’t want to stop and give his stutter a chance to come to the fore? No one knew for sure. But what we did know is that disciplined speaking was not his forte.

Regardless of the reason then, his habit of going off script remains and is not, as some think, a product of his age. Gaffes small and large have punctuated his time in both Congress and the executive branch. Whatever “growth” he has made after serving more than three decades in the Senate and eight years as vice president, President Biden is not that different from Sen. Biden in this one important regard.

In the past few weeks, he has made two hugely consequential off-script remarks. During a September 60 Minutes interview, Biden declared that the United States would in fact militarily defend Taiwan if attacked by China. He followed that up in early October with a remark at a fundraiser that the risk of nuclear Armageddon is at its highest level since the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. It’s clear from the reactions of White House staff that neither was planned.

Putting aside the not-inconsequential fact that there was no intelligence to support Biden’s statement that we are at the brink of nuclear war, were he actually correct in his judgment, it hardly should be casually tossed out in a political setting, devoid of both a serious account of the grounds for his assessment and what the proper policy responses should be. Telling the American public that a catastrophe of world-changing proportions is possibly just around the corner in an off-hand remark leaves both the American public, and—no less important an audience—Putin and the Kremlin, wondering if he’s being serious. One thing we know from decades of the nuclear standoff with the Soviet Union is that clarity of signal sending is critically important.

As for his comment about defending Taiwan militarily, even if one agrees about the geostrategic merits of doing so, the fact is that the president has not made the case to the American public for the necessity of going to war against the world’s second greatest power—and all the massive economic and military costs associated with it. And, indeed, the gap between the president’s words and his proposed military budgets to deal with such a crisis suggest, again, a lack of seriousness. Nor are his words likely to be a deterrent to Beijing. If anything, it might well make the Chinese leadership conclude that it needs to act sooner than later to try to unify Taiwan with the People’s Republic, since the Pentagon’s next generation of “super weapons”—such as, a sixth generation air superiority fighter or a fleet of unmanned surface combatants—won’t be procured and fielded in numbers until the 2030s at the earliest.

A president’s words matter, of course. As the Constitution notes, only the president is “vested” with “the executive power.” In other democratic systems, Cabinet officials often carry more weight because they are part of a governing coalition or are leaders of a faction within the majority party in a parliament. A secretary of state or secretary of defense can give 10 speeches on a topic, but, until and unless the president has something substantive to say, it often remains a question of how committed an administration is to a policy.

No doubt White House communication teams are quite aware that the success rate of using speeches to move policies forward by going directly to the American public over the heads of Congress—what professor Jeffrey Tulis dubbed “the rhetorical presidency” in his classic book on presidential speech-making—is low. It’s low in part because in fact Congress cannot be ignored, because most speeches are bureaucratic products that lack rhetorical punch, and because the public has increasingly been habituated to the piecemeal conveyance of information through the internet, Facebook, and tweets.

Yet it remains the responsibility of the president to provide a coherent account of what issues the nation faces domestically and abroad and what his administration believes are the right paths to follow in addressing them. It is not a matter of “selling” policies as much as educating the public on the state of the nation and the world.

Right now, there is a major war in Europe, a possible revolution in Iran, and the likely anointment of a Chinese Communist Party monarch. Not that it hasn’t been clear for some time but “history” has come roaring back, with revanchist powers using military and economic tools to aggressively challenge the international order that the U.S. largely created and has benefited from for decades. It’s not some problem facing the country down the road; it’s a matter for today. As President Biden rightly notes in the administration’s just released National Security Strategy, “our world is at an inflection point.” America is “in the midst of a strategic competition to shape the future of the international order.”

However, it’s not enough to put out a document that will be read by a few thousand security specialists. Biden needs to explain to the American public and, indeed, to our allies’ publics, what is at stake and what commitments and sacrifices are required if we intend to turn the tide of history back in our direction. Off-the cuff remarks, even sit-down interviews with journalists, are inadequate to meet the moment.

Now, it might be that Biden is not up to the moment and, of course, the bully pulpit is so overused that the public stops listening. But that’s not the president’s problem when it comes to foreign policy and national security. Ironically for Biden, he has said too little—or, to be specific, too little of substance.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.