Turn any article into a podcast. Upgrade now to start listening.

Premium Members can share articles with friends & family to bypass the paywall.

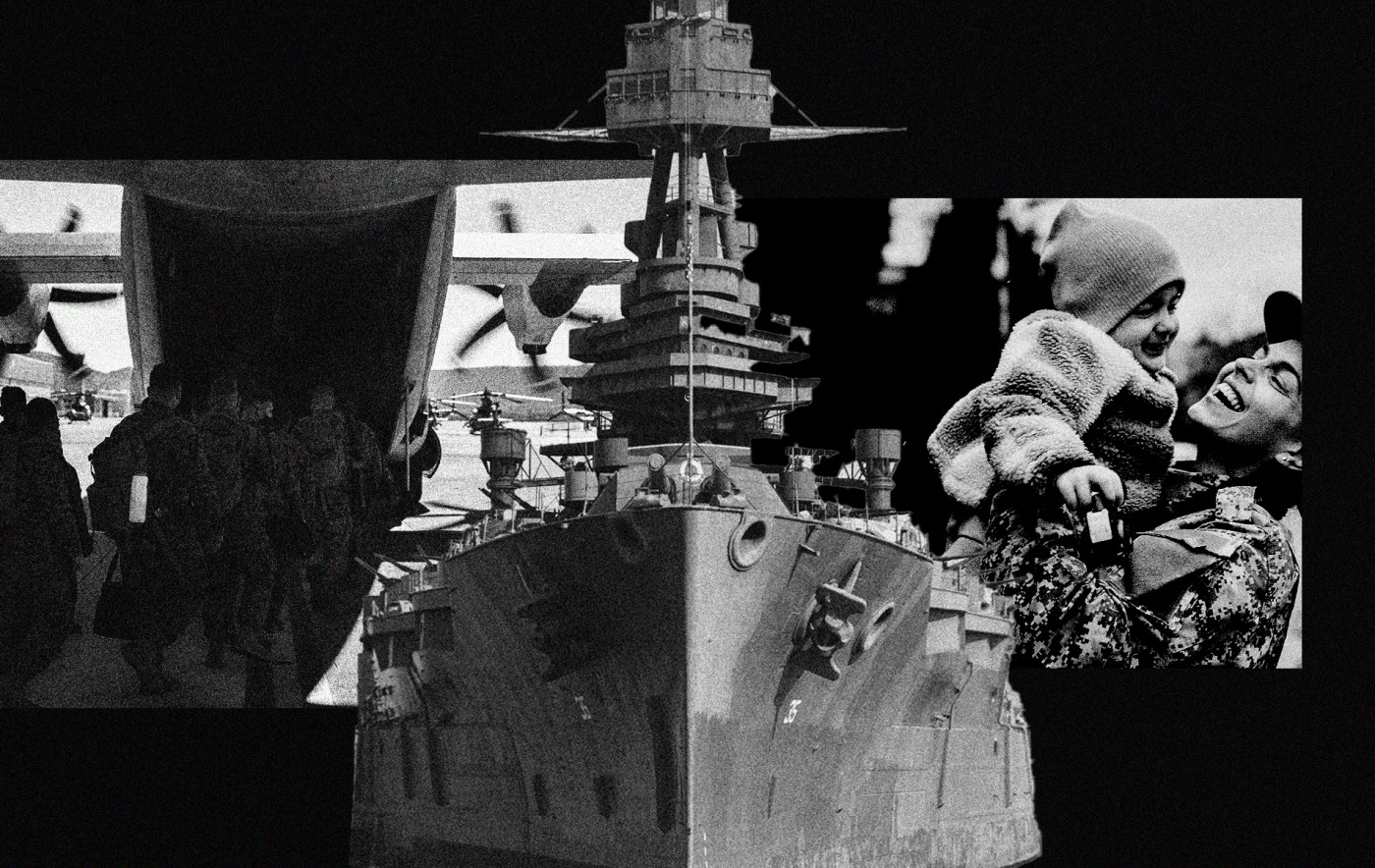

My heart is racing as I sit in my fighter squadron’s ready room refreshing my computer screen. It’s 3 a.m. on the USS Nimitz in the North Arabian Sea. The connection is slow and fragile, and I pray it will hold long enough to confirm the operation was successful. I’m nervous as the image finally downloads—and then I stand and shout with joy. My life has changed, but I don’t yet realize quite how, or that I’ll soon be leaving the military.

The operation in question that night wasn’t military. It was a C-section. My wife delivered our son while I was on an aircraft carrier on the other side of the world. Most veterans have experienced something like this, and service members knowingly accept time away, hardship, and the possibility of death to protect the Constitution. In exchange they receive honor, social mobility, and life-enhancing skills unattainable elsewhere. The all-volunteer force depends on this bargain.

But the bargain is no longer working for many of today’s officers, who are laying down their arms in alarmingly high numbers—and no policy change or incentive seems able to stop it. This is especially true in naval aviation, where I flew as an F/A-18F Super Hornet weapons systems officer. This is not a crisis-revealing institutional failure but rather a natural reflection of America’s changing character. The military is trying to catch up to a changing society and has become an awkward third wheel in the evolving relationship between people and the state.

The Navy is suffering the most from the military’s recruiting and retention crisis, despite some encouraging new numbers. There are too few ships, sailors, and flight crews to sustain the many operational commitments assigned by the competing regional “combatant commands.” Defense-focused publications offer a steady stream of warnings that only immediate, proactive reform can save the institution. It seems the Navy, as former Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert O. Work lamented in 2021, is nearly broken.

Like me, many of my colleagues had aspired to fly fighter jets since youth but searched for the exits after multiple stints in the South China Sea or Middle East. Our families lost steam for the deployments and grinding pace necessary to earn command of a ship or squadron. It was the classic tension of military life. Frequent deployment extensions were (and are) extremely frustrating. In 2019 the USS Abraham Lincoln set a new record for longest deployment since the Cold War as its policy-prescribed seven-month cruise extended to 10. COVID-19, combined with the first Trump administration’s twilight objectives in the Middle East and Somalia, caused extensions of multiple ships including the Nimitz, which set an even newer record on the longest cruise since Vietnam. Defense of Ukraine prompted the extension of the USS George HW Bush in 2023. USS Carl Vinson and Harry S. Truman were both recently extended to support operations against the Houthis. For my family, it was much easier to blame the Navy for being broken than to admit that our needs were changing.

The high operational tempo is a contributing factor to dissatisfaction, but there have always been long deployments, and they have often been lethal. Each deployment record set by a carrier during my career was caveated as being the longest since a previous cruise, not the longest ever. Time away is hard but it is typical of U.S. military life.

“Today’s retention crisis is not merely a byproduct of increased deployments or civilian competition but reflects a fundamental shift in the values and priorities of younger Naval Aviators,” explains Dr. Bill Sherrod, a former aviator now spearheading retention research. He has collected an impressive body of evidence showing that there is “stark mismatch” between what young aviators expect of their experience and the reality of military life. More strikingly, Sherrod notes disillusionment with “a rigid career path that offers little autonomy.” Disillusionment contributes to a mistrust of leadership and, ultimately, the institution of the Navy. Service members are seeking something in the U.S. military that they cannot find. They are seeking freedom of choice. It is not the military that has changed, but rather people’s expectation of what the government is meant to provide.

There is no more fundamentally American value than freedom of choice. Millennial and Gen Z professionals’ quests for work-life balance, job-track customization, and creativity are well documented. Yet choice is a right largely surrendered in the traditional bargain with the military. Resultant retention issues were foreseen a decade ago. A friend of mine encapsulated the search for agency in his military career when he told me, “I was born for creative and iterative problem solving. I am going to get out of the Navy because I can only do that kind of work on the outside.”

We may be transitioning to the “market-state,” a concept proposed by influential constitutional scholar Philip Bobbitt, in which the legitimizing role of the government is to provide freedom of choice for its citizens. This is a natural evolution from the “nation-states” that existed to provide collective security and well-being. With no real existential threat, it follows that citizens seek defense not from war but from structural limitations. This yields a new bargain between the citizen and state where the service member might offer the same hardship and risk in exchange for tailoring one’s own military career track while maintaining work-life balance. In this regard, young officers’ search for balance is neither a sign of weakness nor a crisis.

The declining appeal of the traditional military career is apparent in the growing distinterest in command positions. Commanding a ship or squadron is the crown jewel of the traditional bargain between the state and its service members, with its promise of honor, prestige, and status. It has traditionally been a career apex and the object of intense competition. Yet younger officers aren’t interested given the inflexibility that comes with that career path. Sherrod finds that only 31 percent of first-tour aviators aspire to command.

To adapt to the expectations of the modern citizen, the military is faced with somehow enabling freedom of choice and work-life balance in a career that demands commitment to the point of potentially dying for the country. Bobbitt philosophizes on the military’s conundrum when he asks, “What strategic motto will dominate this transition from nation-state to market-state? If the slogan that animated the liberal, parliamentary nation-states was to ‘make the world safe for democracy’ … what will the forthcoming motto be?”

I often heard officers swear that though their peacetime service felt rudderless, they would return to fight in a war against China. Fighting in a third world war held appeal, but training and deterrence didn’t. Soldierly ethos, despite allegations to the contrary, are alive and well. In the traditional bargain, sacrifice of freedom was necessary to protect the nation. Only fear of a threat could justify such sacrifice in the market-state.

The Navy has been competing in a pseudo-Cold War with China for well over a decade. But so far China doesn’t elicit the emotional and collective response across society that the Soviet Union or al-Qaeda did. Each attempt to pivot the military toward deterring an invasion of Taiwan is stymied by a new crisis in the Middle East or noncommittal domestic politics. Decaying nation-states transitioning to something new are less equipped for prolonged strategic standoffs. There is still altruism in the American spirit, but there is diminished resonance in making the world safe for democracy. Yet the U.S. military is engineered to do just that.

So far, no large-scale systemic changes to address officer retention have been implemented other than monetary incentives. Operational demands are consistently met despite extreme wear and tear on people and materiel. What to do next is dependent on how serious the U.S. is about growing the fleet. This is a complicated question as the defense tech industry explodes with revolutionary advancements in AI, unmanned systems, and mass production. Retaining young officers to operate legacy fighter jets and capital ships feels a bit like holding cavalry officers for the first World War.

To credibly deter China with weapons currently in service, the Navy will need to retain more officers by engineering itself to produce freedom of choice. Sherrod recommends “an AI-enabled digital talent marketplace” similar to those used by major tech companies to allow officers to customize their careers. This is a commendable step toward a new bargain. But the Navy is a lumbering institution. It will take time to fundamentally change how officers manage their careers. Even then, systemic institutional tweaks may not overcome the search for choice and the public’s disinterest in war with China. More importantly, Sherrod recommends the implementation of a structured mentorship and coaching program to help young officers better understand the realities of military life and what to expect from continued service. Such a mentorship program can help newer service members understand and build trust in the institution without mandating massive structural change to the military’s character.

There is reason for hopefulness, at least in naval aviation. Many strong, intelligent, and talented officers remain on duty and at sea. Officers who endured the same familial strain over the same challenging sea time were undaunted and retained intense focus and enthusiasm for flying fighter jets. Some are now entering into their command tours with families steeled for another round of deployments. Officers like them ensure the military accomplishes its many missions, including the yearlong war in the Red Sea that received little public attention before the Signal incident. The traditional bargain is worth it to them.

I met my son on a sunny February day at Naval Air Station Lemoore six months after his birth and nearly 11 since I had left home. My family began to lay the groundwork for a new life made possible by my military career. Thanks to prior enlisted service, I was just a few years from retirement even though I was only a mid-career officer. We decided we could get through one more tour, but that would be the end. I lived my dream of flying fighter jets for 13 years and since January have enjoyed life in Northern California with my family. All the bitterness evaporated when I realized that the military really hadn’t changed. We had. I am confident the military will catch up, however slowly, to the evolving society it protects.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.